Simon & Schuster

340 pages, $25

Review by Sara Lippmann

The unfortunate case of Dear Lucy is one of poor packaging: square peg, round hole kind of thing. This novel, at its core, tells a twisted, dark story, full of grit and desire, promise and protest and crimes of heart. Sarkissian is a talented and ambitious writer with a natural ear. However, she needed an editor to trim the fat and repetition that bog down the book, and to allow it to be what it seems begging to be: a smart, slim, offbeat tale of longing and difference and love, about how to carve a home in the world when the world shuts you out.

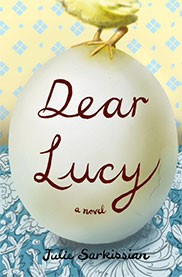

From the outset, the message is muddled. With its sunny colors and whimsical, lighthearted 50s style, the book jacket of Dear Lucy is misleading. This is not a cheerful, breezy narrative about letter writing, chickens or eggs. This is a heartbreaking story of a mentally-challenged young woman whose mother has dumped her on a farm owned by crazy abusive Christians and the friendship she forms with a pregnant teen who has been similarly ostracized. Together, they struggle for independence and understanding.

The structure is impressive and told from multiple points of view: Missus, the caretaker of the farm, who years ago all but pushed her husband into committing incest with an adopted child named Stella; Samantha, the pregnant teen; and Lucy, the mentally compromised outcast with a baby chick in her pocket, and by far the most striking and original voice. Her unique story draws the reader in, and remains the one in which we stay the most invested.

Dear Lucy starts out strong, in media res, in the kitchen of Mister and Missus’ house, the farm where Lucy’s mom has sent her. Sarkissian does a masterful job of dropping the reader down into the middle of this world. Through Lucy’s startling, unusual point of view, we see the breakfast table – Samantha, Missus and Mister. The scene is tense, strange, ominous. They are making eggs. It is Lucy’s job to retrieve them from the hens, an act she calls her “best thing.”

Lucy’s lyrical musings on eggs (the oddest of foods, I would agree) are powerful and beautiful. “When you eat something that is alive you take the life for yourself. You can’t think of it as taking life from another thing, you think of it as giving life to yourself.” Sentences like that, reflections that only Lucy can provide, are really why we are here. About gardening she says: “you have to be loving in your touching the dirt like it is the thick fur on a wild animal.” And a dress: “feels like the outside of a peach which is soft but still protects the inside.” There are lines upon gorgeous lines like these.

Divided into three sections, the first part establishes the stakes. The initial 100 pages are captivating. Missus and Mister are in line to adopt Samantha’s baby when she gives birth. Given what we learn about their history of abuse, the tone is perfectly restrained in its awfulness, filling the reader with dread. Lucy longs for the return of a mother who may have no interest in returning to her, who is finally free to live her life independent of a trying daughter. Samantha is a prevaricating bundle of raw desire. The local church gets involved, proselytizing to the impressionable Lucy and teaching her to read. Nobody is right in the head. Lucy may be delayed, but Missus’s motivations are sinister, Samantha can’t get her story straight. Once Samantha’s baby is born and Samantha and Lucy flee the farm, the pace shifts. And yet, because of the repetition, the adventure that follows feels less of a race toward reunion and more like a cat chasing her own tail.

Typically, shifting points of view create depth and perspective to the story being told. Regrettably, about a third of way through the book the voices cease to perform this function; as a result, the later sections, particularly the final section, lags as actions and scenarios are told and retold, the images cycling back on themselves. We get it, and then we get it again, and so on. Had this book been whittled down and edited, in order to keep the narrative continually marching forward, the drag could have been avoided. At 340 pages, this novel would be that much more gripping at a taut 200.

Another shortcoming is the lack of character development. After they arrive on the scene, the characters begin to flatten, becoming less complicated, more singular in their wants, almost one-dimensional. Themes of abuse and incest feel almost exhibitionist, unreal. For example, I never understand why Missus (who can’t have children, who threw her adopted child into the arms of her husband for the sake of procreating a son, who sets her sights on Samantha’s child) would even want a child? Likewise, Lucy’s mother simply comes across as selfish and mean. She may be those things, which is fine. I’m not demanding likability, but I do wish for more roundedness, greater complication to characters’ thoughts and desires.

Even Lucy, the most fascinating of the lot, with her shimmering observations and original, penetrating lines, grows tiresome. Supposedly, she lacks a facility with language. She often says she doesn’t have the words, or that she wants to learn “the words to say the shapes of things inside of me.” But given her sophisticated, poetic fluidity, this becomes increasingly hard to believe. The reader begins to see the authorial hand through Lucy. When she thinks, “Mum mum grabs my foot and pulls me out like I was a gopher going down a hole,” I no longer see Lucy but Sarkissian reaching, overreaching, coming at this character from the outside rather than from within.

Lastly, there is the question of how much can a novel sustain. On top of the heady themes of incest, abandonment and teen pregnancy, there are a few magical elements. In her pocket Lucy keeps a baby chick she’s named Jennifer, who serves as the voice of reason, with whom Lucy has lengthy conversations, which, okay, given her mental shortcomings makes a kind of sense. However, once Samantha starts talking to Stella (the now dead/adopted daughter/young mother/victim of incest) in the woods it raises an important question: How many characters in one novel are allowed imaginary friends? To me, the duality undercuts the intended effect of Lucy with her newly hatched egg.

Granted, I am just one reader.

But it is a pity. Sarkissian exercises an impressive command of language and confidence in her prose and storytelling. When she’s good, she’s excellent. Early scenes clip ahead. There are moments of brilliance throughout, which almost were enough to carry me through. Here is a writer who – despite missteps – has demonstrated remarkable strength and muscularity in her voice, and a stirring curiosity about the world. I look forward to reading what she does next.

***

Sara Lippmann’s reviews have appeared in GQ, The Book Studio, and Publishers Weekly. Her debut story collection, Doll Palace, will be out in September. For more, visit saralippmann.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)