Stephen F. Austin State University Press

118 pages, $16

Review by Eliza Rotterman

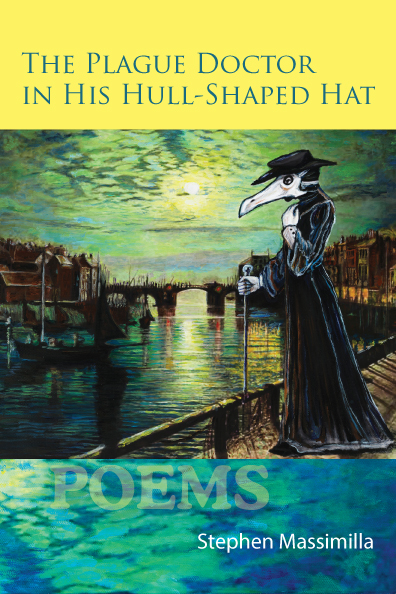

Stephen Massimilla’s new poetry collection The Plague Doctor in His Hull-Shaped Hat begins seaside with the desire “not quite to live forever” but “to take / my fill of you, a long, lascivious look.” It’s an apt start for a book inspired by myth, history and journey. “Teach me to keep going / nowhere,” pleads Massimilla, “nowhere” describing both place—rock and sky—and an enlightened state of mind. From terrain nearly vacant of human presence to Italian cities densely populated and teetering atop towers of myth, the cyclical, Buddhist kind of travel Massimilla speaks of is always on a spiritual plane even while his language reflects a hyper-real, playful sensibility: “Urethra of porcelain teapot hisses,” and teens in “their went-thither hips in zucchini-green denim” traipse by.

Our expectations of travel are often unrealistic. We demand transformation without accepting the terms of pilgrimage. Adrift in his “hull-shaped hat,” the speaker of Massimilla’s poems searches for authentic, unfoldable experience. And at times he seems to find it—in his continued effort to see himself as part of a collective searching for homecoming. “I mean more than consuming,” he tells us in “Etymology”; “I stand wanting.” Remarkably, Massimilla brings loss and disappointment into haptic resolve:

The warmth replaced

with loss becomes part of every other reality,its appreciation, alive to the touch,

touched every which way, every way.

In this case, desire itself is authentic. And what comes after is responsive, bodied, affirming the initial impulse to seek, attach and love.

The Plague Doctor is also concerned with illness and its psychic corollaries of grief and displacement. The epigraphs to the collection—one from an Emily Dickinson letter, the other from Albert Camus’s The Plague—establish our starting point as a meditation on illness and exile. “Doctor as yourself,” Dickinson advises, and Camus asks the reader to reconsider illness as collective exile. And just what is exile if suffered so collectively? And, more important, how to return from this exile? Artists have always been tasked to return us to ourselves, restoring the lost and fragmented; and Massimilla achieves this, presenting the self as in-the-midst-of, inspired, even while acknowledging the modern ailment of alienation. “Before your conquered and conquering rocks/ my flesh, right here,” he writes near the close of “At Capri.” Like waves, one momentous gesture follows another, and the poem concludes with this stark, rapturous dedication: “Here any forever with empty arms/ any man’s ocean-crossing longing.”

I am struck by Massimilla’s vivid descriptions of Italy—vertiginous, enjambed— as well as the attitude of his gaze. His speaker longs “to gaze/ with the reach of gulls feathering space.” A reader of Massimilla’s work for years, I hear tenderness and awe, a commitment to seeing the world as endlessly capable of surprise and delight.

In “Staying with the Mississippi,” where “bone wall dissolves” and “snowy egrets unflock,” we confront a confluence of impulse, and the conclusion of this poem is our first glimpse of the pathos underlying this collection:

where they still stand to cross and get on

with it, maybe not getting this right.

Maybe not, and where everyone crossed, I did. But

You sought the river.

Rivers, oceans: the receptive medium of water inspires Massimilla to exceed his given lot of perception; but here, all of that idealism is stripped away, and we are left with what reads to me as despair. A quieter thread of this collection is lost women— a sister, a mother, beloved friends— and the poet’s intention to let them rest.

I love Massimilla most in these quiet, plaintive moments, when everything is perfectly distilled. “New England Oedipus” is one such poem, with the drama, images and tone working brilliantly together:

This time things would go

listlessly: To side-steppingchirps of the clock, the woman rocked

hrough dark until one blind, blood-scripted eye was opened

and she groaned with surprise.“Don’t” she shushed, to young thumbs

thirling her back, red singeof her brooch-scratch, sunset

easing her into senselessness.

In reading The Plague Doctor, I encountered a richness of landscape and historical breadth made intimate by Massimilla’s confessional streak. Both loss and lostness arise in these poems, and lead to the realization that when it comes to revelation, “there can be none”:

All my life I misunderstood

pain, wandered in a mazeof urban noise.

Never touched an ocean.

These lines from “Time” come late in the collection, but as Massimilla stated while alluding to Eliot in an interview, “In my end is my beginning.” And in the spirit of permeability, Massimilla plays the role of the plague doctor and the patient, doctoring his wounds alongside the rest of us.

***

Eliza Rotterman’s poetry and reviews have appeared in The Colorado Review, Interim, Fourteen Hills, and Poetry International. She has received two fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and appeared as a guest host on the Portland-based podcast Late Night Library. Currently, she lives in Portland, Oregon where she is completing her first book of poetry and studying nurse midwifery.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)