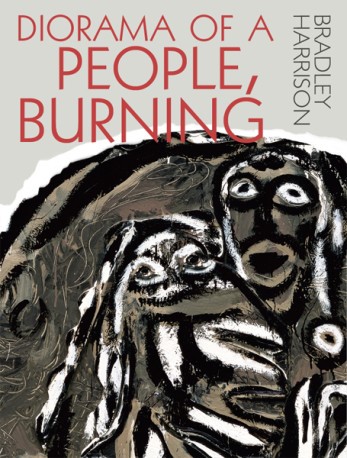

33 pages, $15.00

Review by Hannah Rodabaugh

Several years ago, when I first read Ronald Johnson’s radi os, an erasure text with Milton’s Paradise Lost as source material, I was fascinated by the construct of erasure in the meaning of language. Though the intended product was inconsistent in its desire towards an aesthetic reading experience, it asked questions about interpretation and intention which were interesting in their own right. Put in a different way, a need for structure to display a level of content seemed the point of the erasure. These types of texts often contain intentions in making meaning as one of its forms of making meaning.

In this vein, Bradley Harrison’s short collection Diorama of a People, Burning is neatly exposing these intentions. The chapbook is a wave-like series of text erasures. (This wave-like structure might be intentional, as many references to the catastrophic flooding in Iowa a few years ago occur intentionally and often.) The erasures center around six prose poems. Each prose poem has a series of three corresponding increasingly erased versions that follows it. In all but the last series, they are in order of least to most erased, which gives us a sense of everything falling away as we read.

The collection begins with a lyric erasure sequence that illustrates this falling away nicely. The initial poem, “Her Problem of Gravity,” contains the following passage:

Dressed all in yellow despite her pale skin, Isabella coming slowly

down the hillside, white umbrella overhead, thick punch the sun. It is

mid-July in the mid-Midwest. No rain for days. There are swallows

humming circles overhead, tracing a slipstream she will try to enter

into, never find her way out of. The streets below are mostly vacant:

some garbage, some couples, Alessandro sweeping and smoking in front

of his Italian café. Old men hawking chaw toward the cracks in the

sidewalk, talking the weather. Mostly not talking.

At this point, the poem’s language is a sort of maximalist, pedestrian experience. Once we get to the first erasure version (entitled “Her Prob e of Gravity”), the passage is whittled down to a gorgeous sequence:

Dressed in her skin, coming slowly

over thick

July rain

she will try to

find her way out of

weeping in front

of his

Mostly not talking.

Something achingly lyrical seems to pour forth from a subconscious understanding in the passage. That the first poem had this hidden relationship to others in it is wonderful, like opening a wrapped gift.

By the last poem in this sequence, the first text has been so erased that nothing is left in its place but a simple, koan-like statement which reads, “In / rain / she will try / not / to / wallow / in / the / unknown.” The tone is spare and lyrically precise. This type of restricted uncovering occurs successfully in many other sequences in the collection. It’s one of its strengths.

Many of the poems deal with a catastrophic flood; an invocation to Colfax, Iowa in the epigraph (Harrison’s hometown) must be a response to the overwhelming floods in 2008 which blanketed the Midwest, and multiple repetitions of language that are centered on rain and rising floodwaters appear in many places in the collection. They often try to recreate the feeling of the floods. The poem “Everyone Loves Spook McConnell” has these lines: “Think fields of / dark sky. Think only to rise. The riverbed streets. Hands everywhere / reaching, the texture of bread.” In another example, the title poem “Diorama of a People, Burning” contains the lines, “The peculiar grandiosity of every small thing. A mouth touched of water . . . / The particular circularity of every small living in every small / town. A bicycle tire floating in water.” In many ways, the flood and its aftermath explain the need for the segmented structure of erasure. When my relative’s basement flooded after a herculean line of thunderstorms pounded their area with absurd levels of rainwater, what was salvageable after the water receded was not what was significant, or congruous, and what was ruined was like a kind of erasure. Harrison suggests this in the poem “We Rise When We Can.” He writes:

Eventually it all spills over. The levee fails us again: a collision of town

and the world it falls into: dank twilight, the essence of ferment …

Redneck gondolas plow the streets. Camera crews from the regional news

broadcast from rooftops, hilltops, with one brave anchor anchored

to a lamppost . . .

And for the first time in months they are speaking of love: for the

cabinets, handcrafted; her grandmother’s armoire. For his collection

of original issue LPs, adrift in the kitchen. To the strange tongue turning

the world: I don’t know why nobody told you how to unfold your love.

The sense of loss is palpable, and meaning–making ideas or objects are subsumed to a state of absence. The landscape is a language that can be erased.

It is, after all, in a landscape where our writing occurs, and an intersection between the two is an intimate structure. For Diorama of a People, Burning, erasure is the most fitting way to illustrate it. Readers of this text will enjoy the lush, beautifully written prose poems, but what will hold their sustained interest is how those same poems transcend their language as it is removed.

***

Hannah Rodabaugh received her MA from Miami University and her MFA from Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School. Her work was included in Flim Forum Press’ anthology: A Sing Economy. Recently, her work has been published in Defenestration, Used Furniture Review, Palimpsest, Similar:Peaks::, Horse Less Press Review, Smoking Glue Gun, and Nerve Lantern. Her chapbook, With Words: Verse in Concordance, is forthcoming from Dancing Girl Press.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)