186 pages, $15

Review by Sara Lippmann

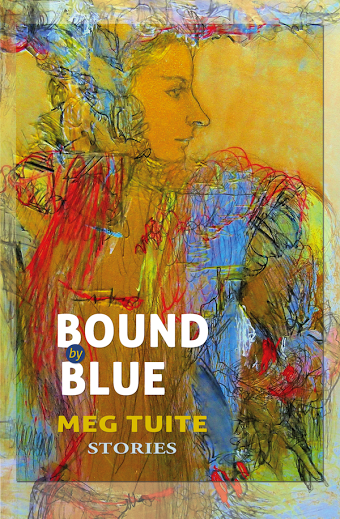

The title delivers. Bound by Blue is everything it promises to be – a haunting, heady collection about those shackled, bound by their individual brand of blue – pain, aching sorrow, screaming memories of childhood trauma. Meg Tuite takes on the awful, the tormented, and the twisted like no other writer. Her characters are not ones to seek out for a moonlight stroll or to cozy up beside on the couch for a breezy rom-com. They can be terrible, but we understand them as survivors; they have suffered from and remain inextricably tied to the brutal, never-ending cycle of abuse. Even when they are unforgivable they are human. The thirteen stories feel almost feral, boldly defying conventional norms with lyrical complexity and startling imagery. Tuite’s prose is fearless and fanged, exquisite in detail – mirroring the barbed edges of her characters whose nightmares stalk them long into dawn.

Hurt is everywhere. Almost all of Tuite’s characters are victims of unspeakable acts inflicted upon them by mothers, fathers, random boys, local men, and other family members. A go-getter medical student is ruled by her eating disorder, the outgrowth of a savage backwoods assault. A grown man gouges out his eye, irrevocably ruined by his own mother’s sexual coercions. A child tears out her own tooth as a cry for help against her older brother’s friend, a predatory neighbor. A caretaker to an elderly man is haunted by the cries of a demented, downstairs tenant. A delusional housewife can’t escape the damage of a destructive marriage and a childhood rape.

“We were all wounded in some way and seeking help. I understood them,” says the suicidal narrator of “The Healer,” the stand-out final story. Driven by a singular desire to “release the me that screamed from inside my windowless room searching desperately for the key to be saved,” she saves up for a trip to Brazil to visit a purported guru for a salve, a panacea, a mere respite from her internal demons.

Tuite’s characters are trapped within the walls of themselves, desperate to but more often than not, unable to outrun their pasts. In “Break the Code”, a dying mother counsels her daughter, “Break the code, baby,” change the pattern of your life. Yet despite this flash of clarity, elsewhere the ailing mother’s message seems contradictory: “Listen to the voices that walk inside of you. They will always lead you to those places you don’t want to go.” Why, then, should her daughter, “listen to” instead of “run from” those voices? The mother makes a final plea, “Peel off another layer, baby.” Until you hit – what, exactly? Bedrock? An infinite number of layers? The daughter’s solution: a slip of LSD on the tongue as a means of evading the path laid out for her, a relatively empowered choice compared to the hallucinatory fallout of other characters, such as Edward in “Bound by Blue,” who never break free.

These are characters that have developed tough exteriors to protect themselves from their pasts, from themselves, from potentially violent presents and futures. On more than one occasion Tuite invokes the allusion of entombment, as an almost aspirational longing. Entomb is the final word of “What Was That I Was Searching For?”, which reads like a litany of heartbreak, with a structural nod to Susan Minot’s iconic story, “Lust.” The writing here is devastating, turning on the line with quiet precision. Elsewhere in the collection, Audrey, the med student with PTSD from “The F Word,” welcomes the sweat from a run as a form of encasement “insulating her in a second skin.” Coping mechanisms include dissociation: “I was a deserter of my skin when I needed to be,” the narrator says in “Drive In,” as she recalls a series of empty sexual encounters.

Beneath their hard shells they are ticking time bombs. “The most difficult part …was to pretend that I was just like everyone else and that I wasn’t a volcano about to erupt,” one character says. This kind of duality abounds. In “Family Extravaganza” the narrator, an employee at KFC, is canned because “I saw rats masquerading as chicken” – a kind of “wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing” metaphor: no one is ever how they seem. The most seemingly banal can be grotesque. Lacey, the central character of “Lacey’s Night Out,” may be in the throes of an extended delusion involving Pat Sajak, but her observations on this point are lucid. At the bowling alley, “Lacey watched in horror while a pink bubble the size of a brain popped slowly from the girl’s mouth on to her face. The girl stuck her tongue out at Lacey. God, she despised most humans.”

This is signature Tuite. Bound by Blue is teeming with lines like this, which showcase her distinctive blend of wit, unexpected imagery, and deadpan honesty. Her descriptions of high school are particularly irresistible:

“Every Friday night a throng of cars lined up at Hansen Beach in the parking lot. Someone always brought a keg. Someone always had weed. Someone always had a flask of something hot that blasted away the panic of life in no more than a few deep swallows.”

And:

“I jumped into a truck with a guy who spent seven years never graduating from high school.”

Despite the bleakness of her territory, Tuite never fails to finds light in the mine. Unlike some of her other characters, the narrator of “The Healer,” is not delusional; she knows she’s blown a ton of money on an excursion to some Brazilian who very well may be a charlatan. Not that she had much faith to begin with, but the longer she’s there, the more despondent she feels –

“The days were passing slowly and quickly at the same time.”

“I went to the waterfall after lunch and the hellish meditation room.”

Until there, at the ending, lies a stunning twist. Butterflies surround the narrator, only this blue that binds is hopeful, thanks to all these fluttering, creatures of flight. The closing image provides a poignant symmetry to the final image of “Breaking the Code.” Here, too, the narrator stands alone on rocks. But instead of being surrounded by icy blue, jagged mountains, as in the earlier story, the narrator of “The Healer” locates her peace as “a swarm of the most magnificent blue-purple butterflies whirled and beat their wings around me.” It is an astounding moment in a story that skillfully reveals Tuite’s impressive emotional range. At last beauty and tranquility envelop her, at last she begins to release torment’s grip; in fact, all this time she felt shut-in she “was inside a miracle.”

***

Sara Lippmann is the author of the story collection, Doll Palace. For more, visit saralippmann.com

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)