Instar Books

178 pages, ebook, $10

Review by Caitlin Corrigan

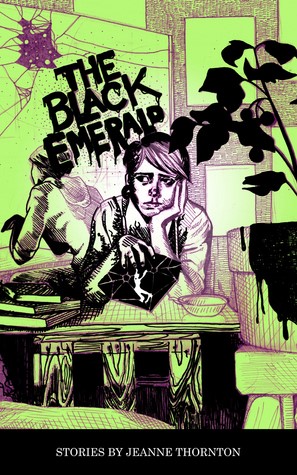

Jeanne Thornton’s collection of stories, The Black Emerald, is consistently smart, sometimes quite brilliant, and almost always just flat out fun.

Published in ebook form by Instar Books, this collection of two novellas and seven stories also contains a few illustrations drawn by Thornton, and is available in a variety of formats, including a slick looking emerald shaped flash drive. Instar Books is a new indie press slated to release four titles in 2015, and The Black Emerald, released in late 2014, is their debut effort. With a model that emphasizes transparency in book sales and electronic only publication, Instar explicitly seeks an alternative publishing model for authors and works that fall outside of mainstream tastes. Their website makes public the number of sales figures for each book, and offers Kickstarter-like perks that “unlock” once a certain number of copies have been sold. The first of these bonuses has already been revealed—a bizarro recording of the author singing “Born to Run”—but I’m going to keep my fingers crossed that these cats make it to 50,000 units, at which point they’ll purchase a ship called “The Black Emerald” and host panels and salons in cities across the world. (See? Way fun.)

Thorton has published a number of short stories in online and print journals, many of which are collected in The Black Emerald. She’s also the author of The Dream of Doctor Bantam (O/R Books), a novel that was a finalist for the 2012 Lambda Literary Award for LGBT Debut Fiction. While the stories in this collection are all strangely engaging, the first, titular novella may be the strongest in the bunch. The plot sounds downright baroque when summarized—a queer teenage girl receives terrifying artistic powers from a magic gem found in the home of her R. Crumb-esque comics idol—but Thorton thoughtfully balances the surreal with the sincere. Reagan, her heartbroken protagonist, is driven by a near obsessive need to rekindle things with her ex-girlfriend, and that passion powers the engine of the first several chapters. Before Thornton lets loose the delightfully weird imagery that Reagan conjures later in the novella, she first captures the ache of teenage longing with precision:

“Josephine rose like a great wave before her, a wave so navy dark it looked black, and if Reagan could wait in one place, feet on some strange surfboard with the perfect balance of tension in her muscles and perfect attention to every shifting current in the water that surrounded her, Josephine would swoop beneath her, lift her, carry her someplace far away, someplace where she could feel the sun on her forehead.”

The teenage voice in this novella is strong, clear, and intelligent throughout. Like a funhouse mirror version of John Allen’s The Fault In Our Stars for queer, artsy kids, Thornton’s characters are articulate and witty, tossing out references to social media, books, and film, but also expressing their own developing emotions with precision. In addition to her girl problems and the challenges that comes into play once the emerald has its way with her art assignments, Reagan also suffers from her father’s constant microagressions. Thorton renders this conflict with chilly complexity; here’s Reagan’s mother after hearing Reagan’s report of being injured by her father’s reckless driving:

“She looked as if she would have been happy if Reagan’s dad really had run her over with the car. Like that would have been an action you couldn’t ignore anymore; like that would have been a doorway.”

Unignorable doorways into other worlds, world more painful and strange, but also sometimes more beautiful, are what Thorton creates in some of the other stories in The Black Emerald. While most of the pieces are fabulist in some way or another, the relative realism of “Putrefying Lemongrass” lays plain a situation in which a trans woman, Rhoda, is approached by a seedy couple at a restaurant. Rhoda goes with them, but feels deep discomfort the entire time. The couple treats Rhoda as a kind of living, breathing sex toy, but shows restraint when Rhoda suddenly dashes out of the room. Rhoda hides out in the stairwell, where she, and the reader, wait for some sort of violent consequence. While waiting, Rhoda considers that instead of feeling anger, the couple will be “horribly kind” to her: “They understood things already that Rhoda didn’t want to understand, that she would spend the rest of her whole life, she was sure in that moment at the top of the stairs, slowly, slowly understanding.” Thornton’s villains here, do more than use the wrong pronouns and buy a woman’s company for a cheap meal, they also force open Rhoda’s doorway to another, darker world.

In these stories, Thornton is unafraid of darkness, but her sense of absurdist humor and knack for creating vivid imagery lets in plenty of light. A beautiful, popular girl humps a human skeleton at a makeout party; a man names his tomato plants after the Brontë sisters and becomes literally entwined in their need for him. In The Black Emerald, Thorton’s door to the weird reveals strangeness, yes, but also the familiarity of complex human emotions.

***

Caitlin Corrigan lives in Portland, ME. Her fiction has appeared in Word Riot, Wyvern Lit, SmokeLong Quarterly, Printer’s Devil Review, the Tin House “Flash Fridays” feature, and elsewhere. Reach her at www.caitlincorrigan.com or on Twitter at @corrigancait.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)