“See Here,” by Ellen Parker

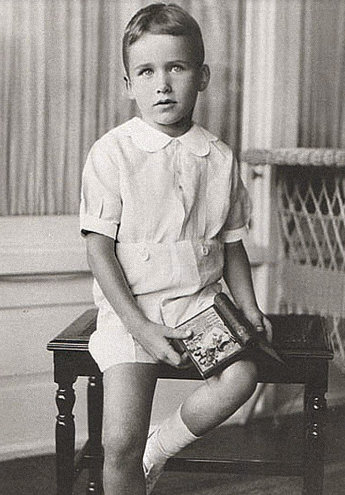

This little boy is my dad. Someone gave me this photo of him shortly after he died. I’d never seen it before then. After someone dies, after the person is no longer available to be looked at, how come people relinquish all these pictures they’ve been stockpiling?

This little boy is my dad. Someone gave me this photo of him shortly after he died. I’d never seen it before then. After someone dies, after the person is no longer available to be looked at, how come people relinquish all these pictures they’ve been stockpiling?

Maybe the mindset is: Now that this person is gone, you might want some clues as to who he was.

In fact, yes. I’ve been looking for clues. I’ve been looking all my life.

Notice his hands. They don’t look like little-kid hands. When he was 74 years old and in the hospital, dying—actually, dead; a machine was doing his breathing, but we were still hoping—I watched his hands rest against the sheets. They didn’t look like old-guy hands. They were the same hands you see in the photo. A little chubbier, though. Fleshier. A little younger.

I’ll say two more things about the photograph, and then I’ll tell one anecdote. Quick. People who go on and on about their dead relatives—well, it’s lovely for the first few lines, but then—.

First, what book is that? It looks charming. I want it. But my dad’s gone and his parents are gone, and I’ll never know what book that is, and I’ll never have it. What happens to old books? They get thrown out, of course, but what happens to them after that? I guess they go into the ground, and turn into earth.

Last thing about the photo: That shirt is killer. Its starchy pallor. Look at that collar. If I saw a shirt like that for sale in a ladies’ size, I’d be like, Thank god. I’ve been looking for this. I would wear it under a black sweater, the petal collar displayed, in relief, against the dark knit. Then again, I wonder, Would this effect be too much? An affectation? It’s possible for something plain to overpower.

The anecdote. From age 16 to age 26, my dad had tuberculosis, and he spent those years in his twin-sized bed in his small room in his parents’ narrow house on Conshohocken Avenue, Philadelphia, PA. He was gravely ill, a young person slowly dying, but, by and by, the doctors gave him an antibacterial that worked. I picture him getting his first dose of this wonder drug and, instantly fit, he throws off the covers and vaults from the bed—but how could this have been?

Still, his recovery was rapid. One of his lungs was partially collapsed, but who could tell? At Temple, the college, he met my mother. I’m sure to her he looked fine.

Soon, too soon, they were planning marriage.

If I’d known my mom then, I’d have talked some sense to her. Wait. You’re thinking of marrying a man who just got out bed after 10 years? There’s no way he won’t be weird.

Reader, I married him.

That’s a very good opening line. But it’s a whole nother story.

And, for this story, it’s the epilogue. This anecdote begins earlier. Thus:

Once upon a time, a young man was dying. Mid-20th century. East Coast, USA. Year 8, say, of 10 years in bed. His body was not well, but his mind was fine. To pass the time? Books. Hardbacks, paperbacks, comics. Newspapers, magazines. Pencils, pads. A deck of cards. Maybe a bedside radio. No TV in his room. Downstairs, the console television was parlor furniture, a blank wooden beast that hogged a corner—maybe the guy would have turned it on if he’d been able to get to it. His mom used the TV like a display table: framed photos on doilies, a curvy blue-and-white vase. Chinese drawings on it. Dear things a well child might destroy.

One of the activities the guy in bed did to pass the time was take and retake I.Q. tests.

Say what? When my dad told me this part, I broke in. Where the hell did you get I.Q. tests?

I don’t know. From books. In magazines.

So you found these tests, and you took them over and over?

Yes.

Why?

I was bored.

Anyway, he took these tests so many times that he had all the answers memorized. Eventually, finally, he got well. So, what now? He’d gone to bed a kid and gotten up a grownup, and he had to do something with himself. He took some classes at Temple. He enrolled in the Charles Morris Price School of Advertising.

He interviewed for jobs. At one of these interviews, they gave the applicants an I.Q. test.

Me: No.

Him: Yes.

We both start to laugh.

My dad had a great laugh—just full on, absolutely unfalse. A person telling a story who got this laugh felt like, I am so owning this. Also, the inverse: Dad’s telling a story and he starts to laugh, and that’s it. The room is in tears. Everyone is dying.

I say, That interviewer, he must have been like: This skinny guy is a straight-up geeenious. Hire him!

But my dad says, Nah. They’d never seen this before. Some schlepper takes this test and he gets a perfect score? Not possible.

I’m like, What I.Q. did they think you had?

Dad goes, An I.Q. that doesn’t exist.

Laughter.

Anyway, get this, the interviewer tells him, You must have cheated.

What’s my dad supposed to say to this? He did sort of cheat. But he didn’t mean to.

What did you say?

I just told him I knew all the answers.

My dad was shown the door. They thought there was something funny about him. Something weird. He had tricks up his sleeve. Cheat sheets.

Soon enough, he got a job at an ad agency and he wrote copy for Hills Brothers Coffee.

Hills Brothers Coffee: Flavor so unbeatable, it’s reheatable.

My dad became Don Draper. First in Philly, then Chicago. Less dapper than Don. But funnier.

I meant to be done here. But I need to say one more thing.

I look at this photo of my dad, a small boy, and I know what happens to him. Is there a word for this experience? Perhaps “prescience.” But that’s not it. It’s prescience falsely gained. It’s prescience for cheaters.

My point is: I look at many photos on Facebook that friends and family post of their kids. These children are small right now. So much is ahead. Their faces look unmarked.

There’s a final line in a poem by a writer named Bruce McRae that appeared in FRiGG last spring and it killed me when I read it:

Every minute is a hammer. Every day is a nail.

I repeat these words in my head sometimes to make myself feel better. Every human, I think, at every minute, can feel the heavy rhythm of these words. We feel it in utero, a heartbeat. These babies, these little kids whose faces we look at on Facebook in the year 2015, they are not unmarked. We just can’t see it yet.

***

Ellen Parker is from Philadelphia, Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, and Seattle. She writes fiction. She is editor of the online literary magazine FRiGG (http://friggmagazine.com/).

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)