225 pages, $17.95

Review by Julienne Isaacs

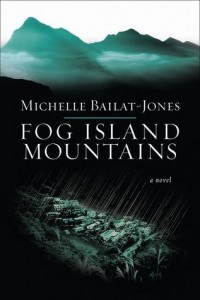

The gloomy cover design of Fog Island Mountains, Michelle Bailat-Jones’ first novel, immediately appealed to me, ripe for a spate of late-winter melancholia: streaking rain over a black-and-green mountainous settlement, the whole layered with heavy titular fog.

But true melancholia denotes passivity or depression, and on that level Fog Island Mountains’ cover design is deceptive. The novel, which won the 2013 Christopher Doheny Award from the Center for Fiction, is self-contained and energetic, as whimsical as it is sad, as playful as it is serious.

Alec Chester is a South African expatriate who has made his home—and his life—in the town of Komachi, Japan, at the base of Kirishima mountain range. In the first pages of Fog Island Mountains he is diagnosed with terminal cancer—news he does not have to pass to his wife of four decades, Kanae, in so many words. She already knows, with the insight of the deeply beloved, and she has fled Komachi to avoid facing Alec’s imminent death.

Cross-cultural communication is a key element of Fog Island Mountains, and one Bailat-Jones, a writer and translator and translations editor for Necessary Fiction, is well-placed to explore. In this novel it occurs on several levels. The story itself is a literary reinterpretation of the Japanese kitsune (or “fox”) folktale tradition, in which foxes are magical beings of great wisdom who can shape-shift into women. In Fog Island Mountains, which is narrated by Azami, one of the town’s oldest and wisest women, the veil between the female domestic sphere and the domicile of the fox is fine indeed.

And within the arc of Azami’s tale, Alec, “a man who has made integration into Komachi a kind of life’s work,” discovers that no amount of time spent in a place, even a lifetime, can completely elide cultural differences.

Alec and Kanae’s story is a narrative thread spinning from Azami’s spool—one of many, the reader can assume. At the opening of the novel, Azami is waiting for the gathering storm to begin: “We will watch the sticky, drizzly rain, the green clouds and gusts of wind that hit hard but do not build, not yet … This waiting the hardest part, and here is Alec Chester, one half of the subject of my poem, of this story that I must tell…”

Bailat-Jones maintains the present indicative tense throughout the novel, an impressive achievement on its own, which also serves to strengthen the reader’s sense of Azami as the omnipotent storyteller. Every vision is filtered through her gaze, and as the town begins to learn of Kanae’s abandonment of Alec, the stories spin faster:

This evening we are learning the first hints of their story and the people of Komachi are wondering what it all might mean. Where has she gone? What is she doing? … So many stories starting up, so many possibilities—we are writing her and rewriting her, forgetting what we know of her character … it is amazing how easily, how quickly really, a person can be turned inside-out and rewritten completely.

What makes an identity strong? What makes a life strong? What makes a marriage strong? Fog Island Mountains fuses these questions, and the answer—which Bailat-Jones hints at in her lilting present tense—has something to do with deep communication that transcends love.

When Kanae flees Alec’s illness she flees her own responsibility, but not until she has left him in every sense is she able to see the need for restoring honest communication with her husband. But even in this spirit of returning, the form of Kanae’s communication is not dependent on Alec’s presence, but rather her own internal openness:

… she begins a dialogue with him in whispers; in the familiar hushed tone of their intimate conversations … she explains what she is doing, she gives him a litany of her smallest actions—how she must push on the pedals, hold the handlebar with a firm grip …

Fog Island Mountains’ thesis is a brave one: vows, once spoken, can transcend the need for speech. But their power is dreadful—they compel us to return and return again to the sites of our deepest weakness. And as Azami shows us, our task—as Komachi within the story, as readers with-out it—is to hear the vows as they are made and listen to the story until it is finished.

***

Julienne Isaacs is a Winnipeg writer. Her essays, reviews and interviews have appeared in The Globe & Mail, The Winnipeg Review, CV2 magazine, Whether magazine, The Rusty Toque and Rhubarb magazine. She is staff writer for The Puritan’s blog, The Town Crier.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)