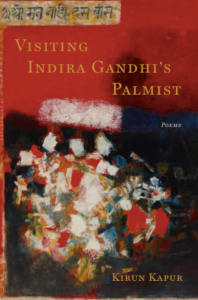

104 pages, $17

Review by Meg Eden

Kirun Kapur has a love-hate relationship with history. Her debut poetry collection, Visiting Indira Gandhi’s Palmist, is an embodiment of history—not just her own, but the archetypes that build history itself. Kapur is situated within both eastern and western culture, and carries such a rich family history that it’s almost as if she’s compelled to be involved in conversation with history, whether she likes it or not. In her poem “Under the Bed” she says, “I didn’t need monsters, I had history. Didn’t want history, I wanted crime—“ But despite “not wanting history,” Kapur uses it fully as a successful medium for her poems.

While many of us write about our family histories and narratives, Kapur reminds us what makes a successful retelling of history. Kapur begins the collection with a quote by Willa Cather from O Pioneers, “There are only two or three human stories, and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they had never happened before…” This quote perfectly sets the landscape and ideology behind these poems, which do not rely solely on their own uniqueness but affiliate themselves with a history of human stories. What’s so great about what Kapur does is that she doesn’t isolate her family poems, but marries them alongside biblical and Hindu narratives, using these archetypes to place her family narratives in a larger context and history.

Despite the specificity of her family’s history, Kapur is profound in speaking on the human experience at large. She even allows her family to inhabit the mythological stories, so that the line becomes blurred between history and myth, her family taking on this almost other-worldly embodiment.

Kapur’s decision to take ownership of her history is particularly clear in the title poem, “Visiting Indira Gandhi’s Palmist.” Having her palm read, she concludes after being told that she’ll be “a good wife” and have “many good sons”: “I made up my mind right then to open my hands—their forked wires, their lines of names and places—take them.”

This very act of writing about her histories not only grants Kapur ownership over them but also allows her to memorialize them. This idea of memorializing comes up most clearly in section two, starting with Urvashi Butalia’s quote: “Millions may have died, but they have no monument. Stories are all that people have, stories that rarely breach the frontiers of family and religious community: people talking to their own blood.” By writing these poems, she is memorializing the people whose stories have only remained in “their own blood”.

The ideas of this quote are reinforced through Kapur’s choice to not name many of the family members in her poems. Most of them are referred to their title (aunt, uncle, mother, father, cousin). In Light, we see the aunt referring to the characters as “your cousins and your cousin’s cousins’” and the speaker refer to one character as her “favorite cousin.” We also see the act of “nam[ing] lost aunts and daughters.” In this poem, the names of the speaker, favorite cousin and niece all mean “light,” as if the individual names or differences between these characters are irrelevant—or perhaps not considered relevant by others. This poem is particularly potent in its ability to address political themes and concerns without being overbearing.

Perhaps what makes this content so strong is Kapur’s seeming lack of bias. Her poems are a marriage of east and west: both figuratively and literally. As she describes her parents meeting in “Meat and Marry,” she describes: “A nun and a swami walk into a bar.” Her poems balance Hindu and Western perspectives, acknowledging tension (as in the poem “Factory Fire”), and she provides both perspectives the opportunity to speak. She always gives two sides to the same story, which can be seen most clearly in the “First Families” series, which takes on both Cain and Abel’s voices, but also the Pandavas from the epic Hindu text the Mahabharata. We also see this in the speaker getting perspectives from both parents in the “How it Happened” poems. Kapur’s world is divided by these juxtapositions, but instead of finding tension in them, she embraces this diversity to create a full, thought-provoking collection of poems.

***

Meg Eden’s work has been published in various magazines, including Rattle, Drunken Boat, Eleven Eleven, and Rock & Sling. Her poem “Rumiko” won the 2015 Ian MacMillan award for poetry. Her collections include Your Son (The Florence Kahn Memorial Award), Rotary Phones and Facebook (Dancing Girl Press) and The Girl Who Came Back (Red Bird Chapbooks). She teaches at the University of Maryland. Check out her work at: www.megedenbooks.com

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)