71 pages, $12

Review by Brian Fanelli

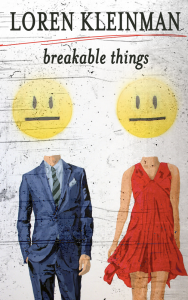

Loren Kleinman’s third collection of poems, Breakable Things, has more than one reference to Charles Bukowski, and similar to Bukowski’s work, Kleinman’s latest effort contains more than one poem about drunken revelry and sexual adventures. However, the poet pushes deeper, beyond poetry about wine and sex. Breakable Things draws a stark connection between love and violence, either mental or physical, while highlighting themes of loneliness, trauma, passion, and moving on from past relationships.

Immediately, the opening poem establishes the theme of loneliness and longing, which haunts much of the collection. In the book’s title poem, the author establishes surreal imagery and juxtaposes it with a speaker whose fragility is exposed by the closing stanza. In the opening stanza, the speaker states, “My kitchen/is the only thing that exists/one room/floating up/above New Jersey’s faults lines,” before confessing in the second to last stanza that she is alone, eating, smoking and drinking in the kitchen, “the only girl in the world/hiding in cabinets/next to breakable things.” Images about lights circling around the speaker and the ceiling acting as its own solar system make the reader feel as buzzed as the speaker. What grounds the poem, however, is the confession in the closing lines, the fact that even the alcohol isn’t enough to comfort the speaker.

The collection proves, however, that isolation can be remedied in many ways, and not just by alcohol. In “Love Poem,” the speaker finds comfort in words, and it is the first poem to namedrop Bukowski. The longing evident in the first poem returns in “Love Poem,” especially its opening stanzas:

On a Tuesday night,

I get lost

in a love poem by Bukowski.I want to be held

and loved

by someone with big arms,

with ears and feet,

just like me.I think of all the men,

all of them,

their hands holding me,

like the women held Bukowski

in the love poem he wrote.

There is something moving in the plain language and confession that Kleinman employs throughout the collection, but especially in “Love Song,” a poem raw and honest. Unlike the collection’s opening poem, however, the speaker in “Love Poem” finds comfort in words, a cure for the blues. “The lines of the poem fill me up/and make me glow/like a hot doorknob,” the speaker says near the poem’s closing. Yet, there’s also a danger that exists in the poem’s final stanza regarding obsession and love, or even the connection between love’s overwhelming emotions and violence. The “hot like a doorknob” simile is a precursor to the poem’s closing image, when the speaker imagines being smothered in paper, drenched in wine and lighter fluid, and ultimately, lit on fire by Bukowski.

In another poem, “He Breaks Me like a Glass Plate,” Kleinman again explores the theme of violence in relationships. The poem’s opening stanza returns to the image of a breakable thing:

I’m cut on the floor,

porcelain in the skin,

and he breaks

he breaks he breaks he breaks me,

like I’m a plate

on counter top.

The repetition of the word break in the first stanza is especially effective because it causes the reader to relive the violence over and over again. By the end of the poem, Kleinman employs repetition again to show how worn down the speaker is from such violence. “My heart is tired/I’m so tired/so tired/I’m so tired/I wish I was the moon tonight.”

The book’s closing poem, “Keep Smiling,” is one of the strongest and strikes a positive note, specifically the idea that we’re able to overcome our past and keep pressing on. The book’s speaker is literally in motion, moving forward in a car. Halfway through the poem, the speaker is haunted by a ghost of the past, but is able to transcend the memory to keep moving on:

You look through the night

towards something you see,

and you recognize it

in front of you,

like when you recognize

someone you know,

and you stare,

and smile,

and drive past him,passing through him

and he into you,and the night passes

through both of you.

In a collection filled with poems that explore violence, love, loneliness, and past relationships, Breakable Things couldn’t end with a more appropriate poem. The speaker in the closing lines keeps smiling in the face of the past and is ultimately able to overcome it. While Kleinman’s latest collection of poems has more than one poem that mirrors some of Bukowski’s drunken hymns, many of the poems dig deeper to explore, in plain language and well-crafted imagery, the influence of past relationships on the present and ways to overcome past traumas.

***

Brian Fanelli is the author of two books, Front Man and All That Remains. His poetry has been published or is forthcoming in The Los Angeles Times, World Literature Today, New York Quarterly, Blue Collar Review, Paterson Literary Review, Oklahoma Review, and other publications. His work has been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize and the Tillie Olsen Creative Writing Award. He was also a finalist for the Allen Ginsberg Poetry Prize. He is currently a Ph.D. student at SUNY Binghamton and teaches full-time at Lackawanna College.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)