227 pages, $24

Review by Brynne Rebele-Henry

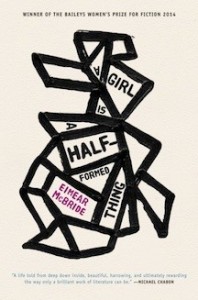

Eimear McBride’s debut novel A Girl Is A Half-Formed Thing is a runic chant for every woman, girl, and infant who has ever been born. McBride’s language is sexual, primitive, almost Stonehenge-like in its spacing and punctuation. The words pound against the page in a style that brings to mind the innermost working of organs in the human body, the language a jumbled elemental call for blood, desolate in its beauty, the prose reminiscent of a desert at four in the morning:

For you. You’ll soon. You’ll give her name. In the stitches of her skin she’ll wear your say. Mammy me? Yes you. Bounce the bed, I’d say. I’d say that’s what you did. Then lay you down. They cut you round. Wait and hour and day.

McBride’s prose is emotionally akin to taking an ice pick to the inside of your thorax—a raw, gorgeous pain. Technically, her prose astounds. The novel is composed of harsh sentence fragments that read like a crooked song. The result is visually, audibly, and mentally stunning:

One in the Ha bike shed. Handlebars dig in my back. He’s all embarrassed I should know the fat spots on his thighs. I have no eyes for that. No ears for any sound emit. I’m thinking counting ticking off. The great work. It’s my great work.

At the lake then two more on the late Saturday nights where they would pass me hand to hand if I would go. I would not. Maybe next week maybe next time. And swig of vodka pressing up my lips. That burn me down. I cannot see their faces or hips that bounce ready for me. I lie. I take my share of them the whole way and there are other girls here. Each one for herself. We don’t look her in the eye. The lads are here for what we are. It makes me laugh. That guzzle and the useless whinging come of them.

The novel constellates the nameless protagonist’s passage from a toddler to a woman, navigating sex and family. She grows up in a small religious country town in England with a conservative, emotionally unavailable, Jesus-obsessed mother and a brother who has a brain tumor, and whom she loves with a sharp devotion. She lives in a sort of impermanence, occasionally making friends, sleeping with random men and boys, sometimes consensually, sometimes not. Her life becomes consumed by increasingly masochistic sex as her brother’s health steadily declines. At its core this novel is a love song to him and to young women in precarious situations.

The lake near her house holds a deep sway over the protagonist, who baptized herself in it after kissing her uncle:

The house will still be quiet. If I go there. Drip the floor. I felt this morning strange beginning. I know. I know I won’t tell. Yet. To Whom. I go. I see the heron fly. Dart of it over my head. Heading are you out to sea? To the newfound world old now though. To a sudden death or a happy mate or a quiet circle or quiet nest. I watch it overhead.

Her mother’s sister’s husband begins an incestuous relationship with her when she is thirteen, and it continues until the end of the book. This relationship is abusive but occasionally disturbingly tender, though he becomes more violent as she slips further into self-destruction.

The plot of A Girl Is A Half-Formed Thing is slow, but the language is dense, fast, and painful. This book is akin to being blinded by the moon: it sears your eyeballs, and you love every tiny wrenching stab of it.

***

Brynne Rebele-Henry’s fiction and poetry have appeared in The Volta, Souvenir, Alexandria Quarterly, and other magazines. She also has published book reviews for Verse. An excerpt from her book Fleshgraphs is forthcoming in Revolver.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)