–by Nichole Reber

Ask for names like Basharat Peer or Tashi Dawa at your local or chain bookstore and the clerks look at you like you’ve got seven heads. I was the one confused, though, by the lack of easy access to international authors upon repatriating back to the States. Sure, I no longer had daily access to ramshackle book vendors beside Mumbai train stations, Peruvian favorites in Lima’s bookstores, or expat bar bookshelves in China, but need that put an end to my colorful reading? So join me in this journey between crisp white pages of new literary titles and soft yellowed pages of older books.

Literary Acts of Worship Terrifies

Yukio Mishima’s Temple of Dawn gave me nightmares. It’s not a frightening novel, not a thriller or suspense, a crime drama or any other form of genre fiction, though it does contain some magical realism elements that prove the literary technique does not lie solely in the hands of Latin American writers. What stole my sleep for two nights, what has me in a terrified yet excited fix to watch The Criterion Collection’s two-disc account of the Japanese author, is his ethereal darkness.

Just a couple of days after opening my first of his books, I put down the novel and started on something else entirely. The next time he came around I stuck with him, opening the pages of Acts of Worship with excited terror like seeing the Blair Witch Project for the first time in a 1999 theatre. This collection of short stories made a better entrée into the troubled writer’s oeuvre.

Translated by Englishman John Bester, whose work on the book earned him a 1990 Noma Award for Translation of Japanese Literature, the stories were originally published over the span of some 20 years and are collected for the first time in English in this book. Acts contains themes that captivated Mishima throughout his writing career all the way through his final and best-known work, the Sea of Fertility tetralogy. His work is charged with religious, homoerotic, socio-economic, and political commentary and filled with poetry, literary references, and other elements of traditional Japanese cultures that enlightens. It also contains an almost gossamer humor that’s easy to miss and usually on the dark side.

The tetralogy includes Spring Snow, Runaway Horses, the Temple of Dawn (where I originally began), and The Decay of Angel. Richard T Kelly, in an article in The Guardian, calls it a saga of 20th-century Japan. Covering 1912 through 1970, the sweeping political statement on Mishima’s homeland contributed to his notoriety.

It’s the pathos and prose that haunted my days whilst reading his short story collection. The seven stories found me traveling through an intellectual and emotional spectrum. At times, spurred by characters’ reprehensible actions, hurling the paperback across the room seemed a splendid idea. At others, I wanted to absorb the stories, if only to comprehend the stimulating plots and dynamic manipulation.

One of Mishima’s most compelling techniques is his ability to delve into the psyches of his characters, a la Thomas Mann. We meet young and old characters who conduct themselves in every way from excessively well-mannered to downright dangerous. Intense development shows characters whose superficial façade as demure and accommodating never cracks, even while stabbing another person’s back with a cleverly placed hand. (In that sense it’s also like Audition, a psychological thriller from 2000 by Japanese director Takasi Miike that haunts me more than a decade after seeing it, yet leaves me ardently arguing it’s one of the best films ever made.)

These characteristics are quite clear in “Fountains in the Rain” and “Raisin Bread,” short stories about teenage misogyny and jealousy. But in “Sword” we get so much more than a bildungsroman. We see layers of character complexity and actions that reveal a fraught humanity within.

“Sword” is the tale of a school-age fencing club at its summer training camp. Two of its members, Mibu and Kagawa, have conflicted relations with each other and Jiro, the near-perfect fencing leader who leads them through schedules, drills, and dietary restrictions like “a god on the rampage.” The dialogue and structure of this and other stories in the collection reveal Michima’s skill as a playwright as well. He builds the plot when the fencing group isolates itself in a camp which natural setting plays a role in the spiraling of this story.

“’The rest periods are for resting, so you’re not to take any exercise that would tire you for the training,’” Jiro says. “’We may be near the sea here, but for you the sea doesn’t exist. If the sight of it bothers you, it means you still aren’t putting enough into the training.’” Because Mishima’s hand is not so heavy in foreshadowing, the reader cannot yet foretell the rebellious scene that will take place in the sea. So unexpected are his plot twists that we’ve no way of foretelling who will rise, fall, or worse.

The story’s crackling tension comes to a head as two strands of rebellion unravel and snap to a surprising end.

“Exactly what had happened? He put the question to himself again. Simply that the others had gone for a swim while the captain was away. That was all. And yet it had been enough to make something collapse—collapse once and for all.”

“Sword” left me quite literally breathless. In fact Mishima’s magical literary tricks here left me dumbfounded weeks later.

Mishima blends strong characterization and an unpredictable plot again in “Act of Worship.” Here we see him as master of misdirection. In this final short story of the book, readers follow the aged Professor and his protégée-cum-acolyte, each of whom has become a self-made caricature, as the former searches for burial places for three wooden combs within the grounds of Shinto/Buddhist temples. All the while we wind deeper and deeper into the motives behind their unorthodox relationship and this trip, which seems to protégée Tsuneko to come suddenly and mysteriously. The more pseudo-academic attention Mishima pays to these holy sites that are “the land of the dead,” the more we connect it with the age of the Professor and his sadness. As he and Tsuneko climb up steep mountain steps, we begin wonder Is she going to kill him? Is she the one who’ll die? Will one of them fall down the Nachi waterfall?

Mishima blends strong characterization and an unpredictable plot again in “Act of Worship.” Here we see him as master of misdirection. In this final short story of the book, readers follow the aged Professor and his protégée-cum-acolyte, each of whom has become a self-made caricature, as the former searches for burial places for three wooden combs within the grounds of Shinto/Buddhist temples. All the while we wind deeper and deeper into the motives behind their unorthodox relationship and this trip, which seems to protégée Tsuneko to come suddenly and mysteriously. The more pseudo-academic attention Mishima pays to these holy sites that are “the land of the dead,” the more we connect it with the age of the Professor and his sadness. As he and Tsuneko climb up steep mountain steps, we begin wonder Is she going to kill him? Is she the one who’ll die? Will one of them fall down the Nachi waterfall?

“As she did so, her foot slipped on the mossy rock; she started to fall, and at that instant, with the unexpected swiftness of a young man, the Professor thrust out a hand to help her.

“The hand floated in the roar of the waterfall, the divine apparition threatening abduction to lands unknown.

“Unfortunately the Professor’s strength was not up to the burden. When she took hold of him he started to fall in turn.”

Mishima meanders back and forth between taut and languid prose and calm and tense scenes as dynamically as switchbacks up any mountain road. All the while he plummets readers further into our own psyches until we come out the other side of these characters’ deep-seeded needs.

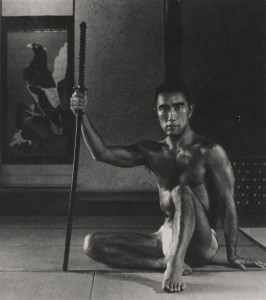

I will return to Mishima’s novels. Later. One must protect her mental health, after all. A friend, likely bothered by my gushing about this Japanese writer, asked if it was the author’s conflicted and enigmatic life—and death—that caused the nightmares. No, if I had nightmares after reading every writer who committed suicide I’d likely live in a mental house. It’s true, Mishima’s work contains a surprising number of suicide-related images that a reader can’t help but see as foreshadowing the end of his life by a gruesome suicide in 1970. But a reader is equally likely to find herself pondering the mysterious writer’s graceful, poignant Japan and its multi-leveled significance of honor and heritage.

Those curious to learn more about Mishima might also consider A Life in Four Chapters. Paul Schrader (known for Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and American Gigolo) wrote and directed this fictionalized account that starts with the day of Mishima’s suicide. It features a Philip Glass soundtrack and an interview in which Mishima discusses writing. https://www.criterion.com/films/588-mishima-a-life-in-four-chapters

***

Nichole L. Reber is an award-winning writer whose memoirs, essays, literary reportage, and lit crit centers on art, architecture, and travel– and sometimes cults. Her work has won awards from Traveler’s Tales and the Antioch Writers Workshop (Midwest).http://www.nicholelreber.com/

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)