By Nichole L. Reber

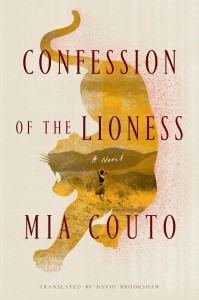

It’d be hard to deny Mia Couto’s sparse detail and simple (though stunningly gorgeous) prose echo that of Papa Hemingway’s. But the fissure between hunter and writer in Couto’s novel, Confessions of the Lioness, makes me wish the two authors could have a public discussion over tea or, more likely, beers. Here’s a line that gets me wondering what Hemingway would have thought:

It’d be hard to deny Mia Couto’s sparse detail and simple (though stunningly gorgeous) prose echo that of Papa Hemingway’s. But the fissure between hunter and writer in Couto’s novel, Confessions of the Lioness, makes me wish the two authors could have a public discussion over tea or, more likely, beers. Here’s a line that gets me wondering what Hemingway would have thought:

“There’s a time to love and there’s a time to hunt. The two never mix. If I were to give in, I would be betraying an age-old tradition: when one is hunting, one cannot have sex.”

I wonder how the Old Man would feel about the novel’s essayistic undertones. They seem to strive to reconcile his own professional sides. Born in Mozambique in 1955, last year’s Neustadt International Prize winner is one of the most prominent writers in Portuguese-speaking Africa. His books, infused with magical realism and deeply rooted in the political upheavals, languages and narratives of his native land, have been published in more than 20 countries and as many languages. He was short-listed this year for the Man Booker International Prize and lives in Maputo, the capital and largest city of Mozambique, where he writes and works as an environmental biologist.

His prose has a swoon-worthy lyrical intensity, yet his sentences come short and quick. Such poetic majesty does Couto’s pen posses that, though Confessions is only 192 pages, a reader simply does not fly through it. Among one-liner pearls (“To forget such an event, it would be necessary never to have lived.”), and for entire paragraphs his sing-song yet soft-spoken lyricism reigns:

“We all know, for example, that the sky is as yet unfinished. It’s the women who, for millennia, have been weaving its infinite veil. When their bellies grow round, a piece of sky is added. Conversely, when they lose a child, this piece of firmament withers away.”

This kind of language makes it easy to enter the worlds of Mariamar Mpepe and Archangel Bullseye, the narrators of this epistolary tale of lion hunting. Through these characters’ stories Western readers gain a sense of Mozambique after its liberation from Portugal and its subsequent civil war. The novel sheds light on all kinds of divides: between urban and village life; between Muslims, Catholics, and polytheists; man versus nature; and man versus woman. Though, from the perspective of the author’s note, the story is based on real people and facts. It stems from a 2008 experience when hunters pursued lions responsible for dozens of attacks on people associated with an oil company’s seismic prospecting.

“The hunters realized that the mysteries they were having to confront were merely symptoms of social conflicts for which they had no adequate solution,” he wrote. In the case of Confessions, Bullseye, the hunter/would-be writer, has his own conflicts, some of which will be solved for him. The resolution of these conflicts, by magical, superstitious, man-made, or animalistic means makes for a dynamic ride.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which published this translation in July and is certainly one of the most elite names in the publishing world, disappoints for its failure to include at least an introduction by translator David Brookshaw. Brookshaw is a professor of Luso-Brazilian Studies at Bristol University in the UK and specializes in postcolonial literature in Portuguese. He’s translated a number of Couto’s and other writers’ books, and thank the gods for that. My hope is that Brookshaw’s work impresses upon students and other readers both the need for world lit’s proliferation and an appreciation for the art of translation.

In this book (I haven’t read any of Couto’s or Brookshaw’s other works), the translator threads in African languages  such as Shimakonde and Manica that help demonstrate the novel’s socio-political gravity. He tells us, for instance, that the Manican term kusungabanga “means to close with a knife.” In this case when Archangel’s father insisted that his wife’s vagina be sewn together before he left town (a not-uncommon practice in African nations even today) the needle was not sterile which led to dire events.

such as Shimakonde and Manica that help demonstrate the novel’s socio-political gravity. He tells us, for instance, that the Manican term kusungabanga “means to close with a knife.” In this case when Archangel’s father insisted that his wife’s vagina be sewn together before he left town (a not-uncommon practice in African nations even today) the needle was not sterile which led to dire events.

Let’s return now to the discussion of the hunter-writer quandary. From early on, Couto sets up multiple layers of conflicts between a writer hired to report on the hunting event and the hunter himself. They spy inside each other’s journals, for instance. The former is white and short and opposed to hunting. He says things like, “I don’t find it at all heroic to fire on defenseless animals. There’s no glory in such an unequal contest.”

Conversely, the tall mulatto hunter, who also writes but perhaps approaches it like a hobbyist, says things like, “Writing isn’t like hunting. You need a lot more courage. Opening yourself up like that, exposing myself without a weapon, defenseless.”

What would Hemingway, cup of Irish Whiskey in hand at our make believe public soiree, say as he sat across from Couto, who, let’s pretend, had just read those lines aloud? Would Hemingway be able to sway Couto’s hunter protagonist to one or the other side of his conundrum that perhaps writing is a form of colonialism, cannibalism, or scavenging? These are things to ponder while reading lines like this: “How can someone criticise me for my professional activity? I practice hunting. Well, the writer lives on carrion. He embarked on this journey in order to peck at misfortune, among survivors who sorrow in silence.”

Ponder this conundrum, magical realism, and stunning lyrical expression in an excerpt of Mia Couto’s Confessions of the Lioness then buy the book. http://us.macmillan.com/excerpt?isbn=9780374129231

***

Nichole L. Reber is an award-winning writer whose memoirs, essays, literary reportage, and lit crit centers on art, architecture, and travel– and sometimes cults. Her work has won awards from Traveler’s Tales and the Antioch Writers Workshop (Midwest).http://www.nicholelreber.com/

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)