Review by Lisa Rabasca Roepe

Writers will find The Folded Clock by Heidi Julavits hard to resist. Who among us hasn’t kept a diary, often from the time we were children?

“Like many people I kept a diary when I was young,” Julavits writes. “Starting at age eight I wrote in this diary every day, and every day I began my entry with ‘Today I.’ ”

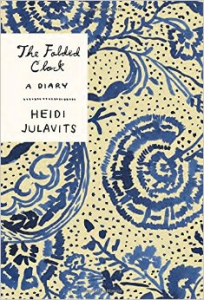

And so begins Julavits’ book, which even from its cover looks like a diary, reads like a diary with dated entries (although they aren’t in chronological order), and each entry begins like her childhood diary. Even the name, the folded clock, conjures up images of a diary because a diary, like a clock, measures time.

And time, as we get older, speeds up. “The ‘day’ no longer exists,” Julavits writes. “The smallest unit of time I experience is a week. But in recent years the week, like the penny, has also become a uselessly small currency. The month is, more truthfully, the smallest unit of time I experience.”

Julavits explains in her book that she recently cited her childhood diary keeping as the reason she became a writer. Yet, in rereading the diaries of her youth, Julavits declares, “They reveal me to possess the mind, not of a future writer, but of a future paranoid tax auditor.”

She begins to keep a diary again. But, instead of diary entries, the reader gets far reaching, broad essays, which explore not just the events of the day but ideas, objects, and topics that interest Julavits and perhaps also touch the readers’ lives.

Objects that are explored include a tap handle, a blue velvet couch, a garnet and rhinestone necklace, and a Rolodex she finds at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York City.

There’s the story of the therapist who stands Julavits up on her fourth appointment, ending their uneasy relationship, and the bad luck ring Julavits bought in Morocco when she was living with her angry ex-boyfriend. “Whenever I wore the ring, my paychecks were lost in the mail,” she writes. Drizzly and cold New York weather allows Julavits to conjure up a story about her semester in Blois, France, and her complicated relationship with her TA when she was 19.

My favorite entry is Julavits’ discussion of a dinner party she throws where she purposefully doesn’t tell her friends who else is invited because she doesn’t want anyone to “pre-Google anyone.” The mark of a failed dinner party, she writes, is when the conversation resembles a job interview.

In another favorite entry, Julavits likens her coat pockets to a diary. “In pockets I have found movie stubs, plane tickets, to-do lists, email addresses written on grocery receipts, business cards from people I have no memory of meeting, reminders that I used to have far more money in my saving account than I do now, jotted down directions (What was at 457 7th Avenue? Who was in Suite 23?). According to my pockets, I’ve been all over this city.”

Although people, places and object are occasionally mentioned in more than one entry, there is no plot. These entries explore the mundane and, at times, are tedious but the overall effect is brilliant. Like an abstract painting that has the viewer thinking, “My child could have painted this,” Julavits tricks the reader into thinking “I could have written that,” when in reality her sparse prose is full of gems like: “The best I could manage, on this day, was to plan to plan for the unplannable” and “One can play only so many card games and eat so many crackers before the familial humor flags.”

Anyone who has found beauty in the mundane and has questioned how small moments make up a life will enjoy this book.

***

Lisa Rabasca Roepe is a freelance writer in Arlington, Va. Her essays on parenting have appeared in Scary Mommy’s Club Mid, Yahoo Parenting, Women’s Day and Mommyish.com. She also writes for The A.V. Club, Men’s Journal, DailyWorth.com and Arlington Magazine. Follow her on Twitter at @lisarab.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)