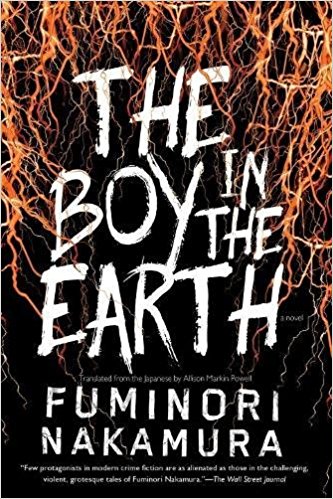

Soho Press , 2017

REVIEWED BY GABINO IGLESIAS

–

Fuminori Nakamura is one of Japan’s most talented contemporary writers. Besides the critical acclaim and translations of his work into various languages, he was won a plethora of awards including the ?e Prize, Japan’s largest literary award, the David L. Goodis Award for Noir Fiction, and the Akutagawa Prize. Despite these accolades, the reasons to read his work are easy to explain: he approaches noir from a multiplicity of unique and seldom-explored angels and injects his dark narratives with a distinctive combination of ennui, melancholy, philosophy, and classic elements of crime fiction. In The Boy in the Earth, his latest novel to be translated and published by SoHo Press, Nakamura turns up the dial in terms of ennui and melancholy to construct a haunting story about a man whose death wish stems from unbelievable trauma.

The Boy in the Earth follows an awkward, disengaged unnamed narrator who drives a taxi around Tokyo for as living after quitting his sales job at a company that produces educational materials. The narrative kicks off with the man picking a fight with a group of motorcyclists and getting a beating for no other purpose than the beating itself. The idea that lead to the scuffle was just one of many the man has been having lately, and they point to a warped frame of mind. At home, he only interacts with Sayuko, a former work colleague. She tries to take care of him after the brawl and they end up in bed, but she is emotionless during their encounter. Later, the man receives information about his parents, who abandoned him 20 years earlier. His mother has died, but his father is still alive. That knowledge forces him to ponder the linger effects of his childhood and how different his life would have been if he had been nurtured. As the narrative movies forward, the man’s past is revealed, and the darkness it holds explains a lot about the nature of the man.

Nakamura always deconstructs violence and explores the relationship between human nature and brutality, both that which we inflict on ourselves and that which we inflict on others. The Boy in the Earth is not different, expect for the fact that the thirst for self-inflicted violence is a mystery to the narrator and reconnoitering the spaces where those thoughts are born and where his need for violence festers becomes a crucial elements of the narrative. This contemplative state begins early and is expressed well after the beating that opens the novel as the narrator thinks back to his childhood, a time in which he murdered lizards:

Grasping a lizard that had already lost its tail or an unsuspecting frog, I would thrust my arm through the fence and suddenly let go. This living thing would fall, and although it wasn’t dead yet, surely it would be a few seconds later. Watching this happen always evoked anxiety, but for some reason, I found solace in that anxiety. In the midst of my agitated emotions, I felt a clear awakening as nostalgia tinged with sweetness spread within me. When I did this, I would also be thinking about “them”—the ones who had tormented me. This habit was persistent in its cruelty; it was almost as if by what I was doing to those lizards now, I was validating what had been done to me in the past, as if I were exploring the true nature of it.

Coming in at 147 pages and with short chapters that make it a very fast read, The Boy in the Earth is one of Nakamura’s darkest, gloomiest, most emotionally draining books. The narrator suffered horribly as a child, and the result is a detached man for whom tedium is a way of life. In that regard, this is a narrative that pushes past all the boundaries usually associated with the genre to enter a unique, obsessive realm where violence, alienation, suffering, the impossible weight of memories, and self-loathing coexist in a maelstrom of pain, shattered innocence, and a very flimsy will to continue living.

Although Nakamura does many things well here, perhaps his greatest achievement in this novel is that it holds a giant secret until the end and reveals it only after showing how the putrid thing at the core of the story corrupted the soul of the protagonist. The writing is fast-paced from the star, but once the visions from the past start appearing in the third act, the lines demand to be read even faster because they reveal the kind of truth that’s simultaneously hard to look at and impossible to look away from:

Beyond the sound of the shovel digging of the earth and the beam of a flashlight feebly illuminating the darkness, I had a hazy vision of their expressions as they spoke hurried Lee to each other, their faces twitching as if they were frightened. I laid there, looking up at them asked, shovelful by shovel for, the earth was heaved on top of my small body.

The time to call Nakamura merely an outstanding thriller author or a very talented Japanese noir master is over; the man has demonstrated time and again, and does so again here, that he is one of the best crime novelist working today.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)