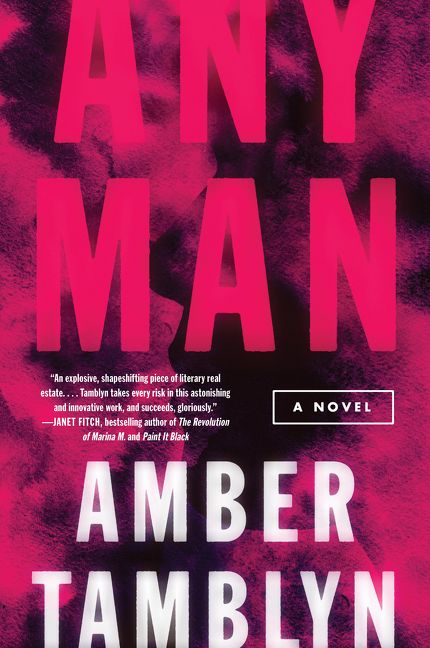

(HarperCollins, 2018)

REVIEW BY S.N. KIRBY

__

Amber Tamblyn’s debut novel speaks to a climate where we face more and more revelations about the monsters that haunt our communities with their self-serving path of destruction and abuse. While the monster in this story is infamous for one peculiarity—this time the sexual predator is a woman, who goes by the name Maude—the unfolding of the narrative plays out like so many others our society has seen. Moreover, it is the public’s schadenfreude and salivation at witnessing this private pain that Tamblyn suggests that we, the public, are perhaps just as monstrous as the predators that lurk in dark corners.

Born in the era of #MeToo and the subsequent disclosures of long standing institutional abuses, Tamblyn’s work gives voice to a cast of men healing after a monster (or is she a woman) destroys their bodies and leaves them naked in the humiliation of her abuse. Some are left for dead. Others are left in their shame. The only evidence she leaves is a six-foot long, white hair.

In the narrative, Maude transforms from human assailant to a mythical creature created out of an amalgam of visceral nastiness. She bounces from human to nonhuman not by her actions, but by the descriptions of her as detailed by the men she assaulted. The first victim, Donald Ellis, sees Maude in a moment of second sight as she moves onto her next victim: “Between the parted woods, a small pair of black eyes peer out and a misshapen scribbled hand claws at the bark, it other arm long, dragging in the mud./The creature is headless./It moves.” Adding to this narrative of Maude, the second victim Pear O’Sullivan goes on to call her, “Maude with cankles and demon egg sacks growing in her gums. Hooved Maude . . . Like a fucking burn victim with babies’ decapitated fingers for eyelashes. With breath like rotting fish and a trail of fur running up the back of her legs and two giant claws for tits.” Here there be monsters.

Something about the physicality of her monstrosity and the way it shifts and changes seems to suggest that there is a shifting component to her selfhood. So often the standard narrative focuses on the transformation of the victims—from victim to survivor—but here Tamblyn seems to suggest that in the very act of becoming an assailant, Maude transforms into a monster. Giving pain is just as transformative as receiving it. But the source of that transformation remains unclear. Is it her soul that is corrupted by these acts? Maybe. For now, the mythical quality of Maude’s physical monstrosity gives her an aura of an omnipresent demon, lurking just outside of our reach.

Maude isn’t the only monster in this narrative. In the echoing and reverberations of voice and power in a media obsessed world, the men left in the wake of Maude are confronted with a cacophony of “support” online and on screen. Through tweets and television transcripts, Tamblyn cleverly reveals the level of entertainment, if not pure enjoyment, society derives from these horrific tragedies. While the author isn’t at a Trump level criticism of the media (no fake news here, folks), there is a kind of blame she places on the media outlets for the way they relish in the private horror of these men.

A caller to Donald Ellis’ radio show, yes he gets his own radio hour, speaks to this quite eloquently, “I realize, more than ever, we need to keep fighting and protecting our kids, not just from predators but also from a society and culture that feels kind of predatory ya know? I mean, that lady did the crimes, but we publicized it. We capitalized on it.” Hey, tragedy makes for great ratings, right? Donald Ellis testifies, “I live in a country built on celebritizing its citizens’ grief and amplifying stories of violence and assault for political gain, click counts, or television ratings. Let me be emphatically clear: They. Don’t. Care. About. Us. People who live through sexual assault are a crash on the side of the road, and the American media is nothing more than cars slowing down just long enough to take a peek.” The condemnation is harsh and swift, make no mistake.

While the public focuses on the monster without, the survivors battle the monster within themselves. Because at the core of it all is a story of healing. This is where readers find a there’s a touch of the mystical in the nightmare. Some kind of unseen magic seems to wind its way around the prose and poetry that is untouchable from tragedy. This magic is delicate but resilient. Tamblyn’s novel reminds us that we can live in a world worthy of redemption. While we can’t destroy the monsters, we can heal the ones within ourselves. Even still, in the concrete jungle of New York, Maude lurks and mutters, “Any man will do.”

__

S.N. Kirby is a graduate of the MFA Fiction program at The New School. Her fiction work explores the relationship between man, magic, and nature. She has interviewed musicians across musical genres such as Ray Toro of My Chemical Romance and Beats Antique. Her National Book Critic Circle interviews with Ruth Franklin and Pulitzer Prize winner T.J. Stiles were featured on The New School writing blog. When she’s not writing, you can find her teaching yoga in New York City. If you smell sage burning, it’s probably her.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)