Editorial Assistant Erinn Batykefer sat down with [PANK] author Dinah Cox to discuss the ins and outs of her new book, The Canary Keeper.

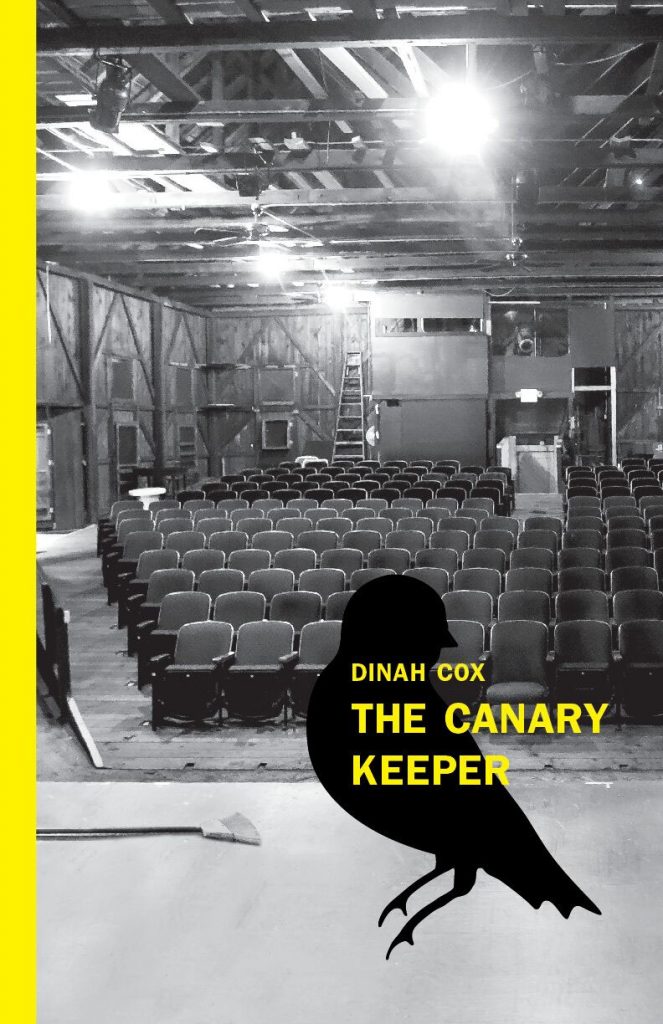

The Canary Keeper himself is a failed actor, the kind of person no one wants to listen to at parties, but the eponymous play he stars in features characters eking out existence while in search of their own curtain calls, a chance to hear the applause before the silence sets in. Artist-citizens from the fictional Market Town look to the dimming spotlight and cannot decide its meaning: are they destined for burn-out or blinded by fantasies of themselves as small-town stars? They mark time by way of darkened, lonely highways, indifference from people in power, and the search for opportunity beyond the boredom of Oklahoma’s borders. They step forward, clear their throats, and laugh at their ability to wait in the wings forever, longing for escape to the green room and anticipating that fateful moment when the stage manager says Go.

Erin Batykefer: Names are slippery in these stories. I’m thinking of “Leo’s Peking Palace,” where friends sing Happy Birthday to Leo and half of them sing “Tiger” because they don’t know his real name, or the way Laura’s middle name, Ashley, is used as a slur in “Snowflake.” How so you see names relating to identities?

Dinah Cox: One of my favorite parts abot writing a story is the moment when a character lets me know her name. Her name tells me much about how other characters will perceive her. Rarely have I written nameless characters—though I think I have a story in which one of the characters is named “The Boss”—because a name is not just a marker but a fixture, a place where one’s origins and one’s future might converge. I’ve become accustomed to people messing up my own first name. In a way, that’s given me a kind of namelessness I sometimes resent and sometimes enjoy. But because my own name is somewhat unusual, perhaps I give more attention to names than I otherwise might.

EB: The stage and the idea of performance is a recurring theme in this collection: politics, plays, talk shows, ballet. Were you a theatre kid?

DC: My parents were very heavily involved in theatre; my father was a professor of theatre history, and my mother did a great deal of acting and directing. My sister, in addition to some other, juicer roles, had the honor of portraying one of the no-neck monsters in Oklahoma State University’s production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. At first, I resisted the family tradition in favor of “making my own way in the world,” but as an undergraduate at Earlham College I majored in theatre, and in my twenties I interned and then worked as a stage manager at an Equity theatre in Michigan. I also spent a memorable summer interning at the Peterborough Players in Peterborough, New Hampshire.

EB: In “Blackout,” I was struck by this line, when the narrator has a moment of panic while arranging props between scenes in a production, only to find the prop cake replaced by a real one: “Had he picked up the wrong cake by mistake–maybe someone working backstage, a real person with real feelings, was having an actual birthday?” There’s real anxiety over real-life consequence of staged performance. How blurry is the line between truth and story?

DC: I worked as an assistant stage manager in a production featuring a birthday cake made of cardboard. It was such a convincing fake, everyone who saw it wanted to eat a slice. So I wrote some version of that cake into a story. But to answer your question, the line between truth and story is blurred enough that, like spun sugar on a real/fake birthday cake, it’s delicious until it gives us a bellyache. Maybe all cakes are made of cardboard after all.

EB: There are a lot of birthdays in these stories–two 21st birthdays, a birthday party not on an actual birthday. What’s your ideal birthday celebration?

DC: I had a pretty nice birthday celebration last year. My partner and I drank elaborate cocktails and cooked an elaborate dinner, drank and ate, and were very merry, indeed. Because all comedies end with a party, I try to have as many parties—throughout the year—as I can; however my parties often include only two people and four dogs: the perfect way to celebrate.

EB: Market Town, where these stories take place, is fictional, but it’s state is real. Why Oklahoma?

DC: The short answer is because I was born in Oklahoma and live here, still. The slightly longer answer is that it’s a sad, haunted, strange, out-of-the-way place, worthy of storytelling.

EB: If you could upload one text into the brains of your readers Matrix-style before they opened your book, what would it be?

DC: How about the American Heritage Dictionary? Or maybe a Post-It note that says, “read a book, robot.”

EB: Anything else you’d like to share with [PANK] about The Canary Keeper?

DC: [PANK] loves you.

Dinah Cox’s first book of stories, Remarkable, was published as the winner of the BOA Short Fiction Prize in 2016. Her stories have appeared in a number of literary magazines and journals, including Prairie Schooner, StoryQuarterly, Cream City Review, Copper Nickel, and Beloit Fiction Journal. She teaches in the creative writing program at Oklahoma State University, where she’s an Associate Editor at Cimarron Review.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)