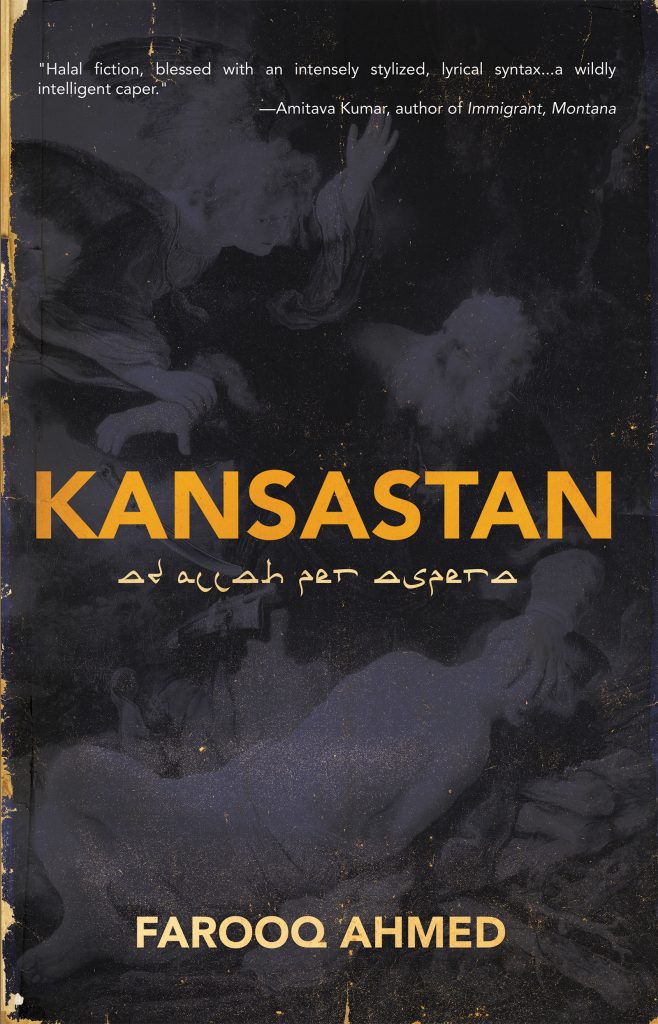

(7.13 Books, 2019)

REVIEW BY J.D. HO

—

One of the important projects of contemporary writers of color or writers belonging to marginalized religious groups is to reclaim and rewrite histories that have largely been recorded and imagined by the majority. Farooq Ahmed’s Kansastan is one such reclamation. Ahmed weaves an alternative narrative of Kansas during the Civil War. His unnamed narrator lives in Imam Bahira’s mosque, slaughtering goats and doing other chores, while around him Kansans defend the state against Missourians. Like a less wholesome Forrest Gump, complete with leg braces, our narrator meets historic figures like the abolitionist John Brown. While the setting is America during the Civil War, on the border between a free state and a slave state, Ahmed incorporates narrative elements from the Qur’an and Islamic history, drawing in particular on the story of Hajar and her son Ismail, ancestor of the Prophet Muhammad. Muslims populate Ahmed’s novelistic universe, and the mosque stands without comment in Kansas. In the Civil War period, Muslims were, in fact, present in the U.S. because a significant number of slaves came from Islamic regions, but that aspect of history is not directly addressed in this narrative.

The narrator of Kansastan at one point proclaims: “If I inherited the mosque, I could retell our stories!” Thus, the main character ostensibly shares a goal with the novel itself. But what is the purpose of retelling and reclaiming history? The tone of Kansastan leans more toward satire than historical illumination or giving voice to unheard witnesses. The retellings seem to be important primarily to gratify the narrator’s ego. In the text, the narrator often feels overlooked, unjustly treated, incorrectly perceived. His sense of injustice increases with the arrival of a woman named Maryam, whom the narrator claims is his aunt. The members of the community regard Maryam’s son, Faisal, as a healer and prophet, while the narrator is the butt of jokes. When Faisal strikes a geyser in the parched landscape, the populace shower him with gratitude, but the narrator complains that no one acknowledges the fact that he was the one to make Faisal play the game that led him to discover the well. That link, he says, “was lost between the storytellers and the told.” The narrator exists only as “the cripple” in songs about Faisal. To combat that injustice, the narrator schemes to take over the mosque by defeating his oppressors one by one.

We know little of our narrator’s past, though we know he is an orphan, that he has a malady that prevents him from walking easily, and that he possesses some knowledge of the Qur’an, though that knowledge is perhaps as unreliable as he is. He doesn’t know Arabic, and calls “ignorance—my shield and my sword.” Despite the character’s ostensible religion and time period, he smokes cigarettes and marijuana (which he calls his “analgesic seasonings”), commits murder and rape, and is generally unsympathetic. In this he resembles some of Vladimir Nabokov’s narrators, whom we are not necessarily supposed to like or trust, and who often have an exaggerated sense of self-importance and a shifty moral compass. Ahmed’s narrator is similar. He seems to bend facts to cast his ethically dubious actions in a positive light. He is our storyteller and our archivist, the compiler of all the information we know about the novel’s world.

As I began this novel, I had trouble getting my bearings because there is little exposition of the factions and historical background of this particular universe. I found myself wishing for more world-building and exposition. I turned to the Qur’an for direction because Kansastan so constantly references the Qur’an and the people in it. Though my reading of it is incomplete and certainly not deep, the Qur’an helped in two ways. First, as I looked up many of the novel’s quotations from the Qur’an, I began to question the narrator’s knowledge of scriptural context. Second, thinking about how to read the Qur’an was helpful for thinking about how to read Kansastan. In his introduction to my version of the Qur’an (Oxford), M.A.S. Abdel Haleem states: “An important feature of the Qur’anic style is that it alludes to events without giving historical background.” Haleem goes on to say that the Qur’an relied upon its readers’ knowledge of events that were, at the time, current. Ahmed employs a similar style, perhaps purposely leaving the particulars of the Kansas–Missouri conflict vague in order that readers will treat the novel as contemporary fable—or satire. Though Ahmed draws upon the Qur’an and the story of Hajar and Ismail, he does not create straightforward parallels.

From an editorial perspective, I think Kansastan tries to take on too many narrative tasks at once. Its satirical elements often clutter the narrative in a way that decreases their effectiveness. (References to Kansas-specific insider jokes, for instance, are worldbuilding, but not in a meaningful way.) But Ahmed possesses the skills to wield a satirical blade, as when the Imam says, “Whom ye war against, I war against,” and much later Faisal says, “If the Lord be for us, who can be against,” echoing both Romans 8:31 and George W. Bush after 9/11.

Another purpose of retelling in the form of satire is to attempt to make sense of—or find relief from—the present, and I think that is where Ahmed’s aim lies. In mocking disability, religion, and the fight against slavery, Kansastan treats nothing as sacred, revealing a deeply pessimistic worldview. The point may be that the particulars of factions and history will do nothing to make sense of the events of our times or the narrator’s. If our murderous and narcissistic narrator is on the side of abolitionists, what does that say about the other side? Perhaps both sides are Fanatics (the narrator’s term), and both sides believe they are right, but, as readers standing outside the narrative, one side’s fanaticism is indistinguishable from the other’s.

—

J.D. Ho has an MFA from the Michener Center at the University of Texas in Austin. J.D.’s poems and essays have appeared in Georgia Review, Ninth Letter, and other journals.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)