The Up Drafts is an ongoing series of essays and interviews that examine creativity, productivity, writing process, and getting unstuck.

—

BY NANCY REDDY

“Is anyone writing now?” a friend asks me via text. “Are you?”

I have not been writing, not in the way I want to, not in the way of my Before life. Writing this column has been hard because I want to offer ways to help, and I cannot seem to help myself. The magic’s gone out of my old tricks. When I think of the rushing-forward, word-count driven, One Thing-obsessed, target-locked-on-the-horizon way of writing that animated me even a few months ago, my chest goes tight and my brain gets muddy. The words just stop. I’ve been reading and running and baking and teaching on Zoom and answering students’ emails. I’ve been trying to help my older son with his subtraction and playing board games with my younger son, who insists on playing Battleship, even though he doesn’t yet know all his letters or numbers or understand the concept of a grid. We watch so many movies, and when we’re all cuddled together on the couch, I can mostly forget my fear that the old life will never come back.

//

When I was in graduate school and teaching intermediate composition, I’d start the course with a list of definitions of rhetoric, a word that’s most often deployed with a sneer, as if all attempts at persuasion, all effort expended in the service of selecting words were automatically suspect. My favorite definition, or at least the one I keep returning to now, is also one of the oldest: Aristotle’s maxim that rhetoric is the ability to, in each case, “discover the available means of persuasion.” The translations I find online mostly use the verb observe, but I prefer discover, for its emphasis on action and changeability: in each case, the available means are different. They shift each time we look for them. Each time we attempt to persuade, we search anew.

And writing right now feels like that, like a new search through unfamiliar materials. For most of us, the time and space and material conditions of our writing lives have shifted immensely. What are the available means for this new version of our lives?

//

I have been trying for two weeks now to write about what’s helping me – about my new available means. One thing that helps is broadening the scope of what I’m willing to count as writing. As C Pam Zhang wrote in a recent craft newsletter for Lit Hub,

Walking is writing. Crying is writing. Talking to a parent whose health you fear for is writing. Cooking is writing. Lying prostrate on the rug and watching sun stripe the wall is writing. Your lover’s hand on yours is writing. Your dog is writing.

For me, this is both true and not true. Much of what I’ve been doing–rearranging tiny spaces in my house, making lists of the items in the freezer and what we can make for dinner with them, the endless laundry–is decidedly not-writing, is instead just trying to busy myself and keep the hum of panic in my brain down. But some of my non-writing activities are writing: long runs, chopping things for dinner, mixing dough and watching it rise, certain kinds of reading, standing on the porch with milky coffee while my kids stomp in the puddles in our now-quiet street. What distinguishes the two, for me, is that, in the latter group, my body is just occupied enough to let my brain work. While running or slicing onions or weighing out flour and water, I am in my body and I can hear the part of myself that writes surfacing again, for a moment. That kind of work can’t be quantified in the way I’ve come to like, but I can feel my brain inclining again toward writing, and that will have to do for now.

//

In the ancient world, the men who taught the art of rhetoric were largely forbidden from practicing it themselves. The most skilled teachers of rhetoric were not themselves citizens and so could not speak in public spaces. I find that very moving now, for reasons I still cannot fully articulate. It is dangerous to romanticize anything about the history of rhetoric, bound up as it is with the history of empire and exclusion. But I have come to realize that much of what I miss about the old life is the casual social contact of public spaces: greeting colleagues and students in the hallway, the awkward shuffle for the sink and paper towel dispenser in the campus bathroom, chit chat with other parents at school pickup at the end of the day. (If what you miss most is a clue to who you are, what does this say about me?)

Though those kinds of casual public spaces are closed to us for now, reading helps me because it reminds me of being in touch with other people. Last week, I read a bad book, or at least a book that disappointed me by falling flat after a strong first couple of chapters, but I was able to pinpoint what I thought had gone wrong and felt a certain writing part of my brain click back on. I read Jennine Capó Crucet’s My Time Among the Whites, a book that’s so smart and well-written, each essay tracking multiple threads that come together in sharp and unexpected ways, and I remembered the vital kind of thinking that happens through serious writing and reading. I’ve been reading The Sewanee Review’s Corona Correspondences, and I love best the ones (like Lauren Groff’s, Danielle Evans’s, Chloe Benjamin’s) that give a kind of intimate account of this new life. This kind of reading is a way back into writing. When I read, I remember what words can do.

//

Because the available means – the empty blocks of time, the coffee shops with other people noisily working away – of my writing life have changed, I’ve also been rethinking what my writing process looks like.

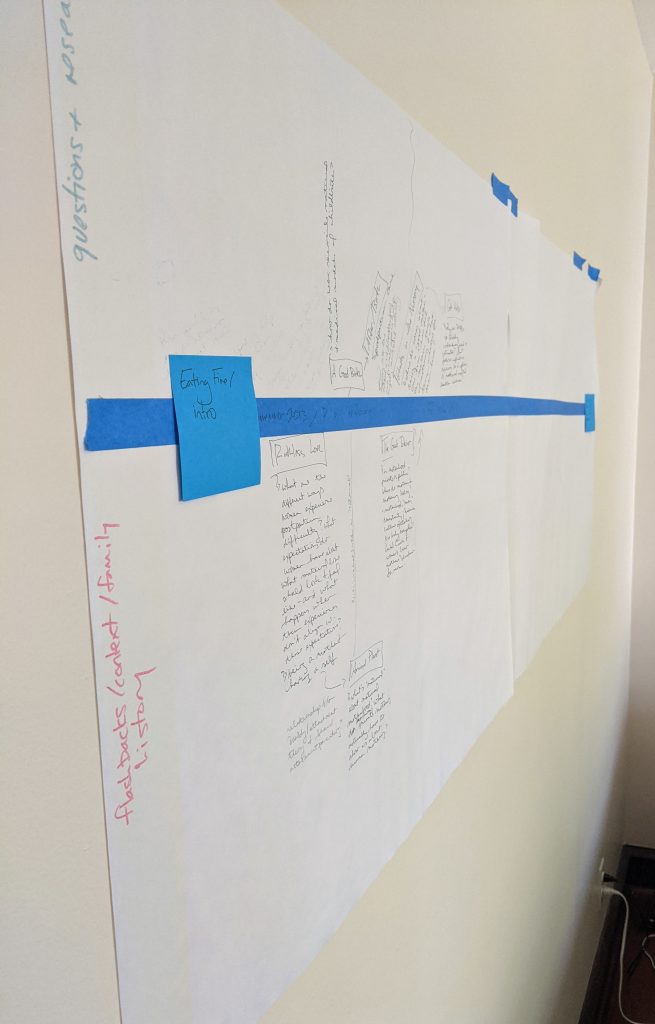

So instead I’ve been trying to sneak up on the writing. I open a document and play around in it. I scrawl a few phrases, standing at my desk, before going to bed, because that isn’t Writing, it’s just making notes. At some point last semester I’d pilfered the end of a pack of large post-it paper from the supply closet on campus, and a few weeks ago, I hung the last two pages horizontally on the wall with painters tape to make a large timeline for the book of narrative nonfiction I’m writing. I’ve started adding chapter titles and notes to the paper. When I make a new connection, I add it in pencil. I draw arrows between the ideas.

This practice has a lot to do with the way I wrote when I was teaching high school English in a demanding charter school system and driving to work in the dark and returning home too exhausted to have a thought. I mounted Ikea curtain rods on the walls of the spare room and used the clips to hang poems so that even when I wasn’t writing (or Writing, in the serious, focused way I wanted) I could be in the presence of the poems. Then, as now, I often got up early to have a few minutes to feel like a writer before the day began. Because I didn’t have long, and because the rest of my life was full of other demands, it helped to have the words right there, as soon as I entered the room. I’m reminded also of Melissa Stephenson’s description of writing in “confetti time,” capturing snippets on hotel notepads and index cards in ten and twenty-minute increments. (Her Lit Hub essay details the index card method, and it’s the kind of low-pressure exercise that I think would help many of us now.)

So these are, for now, my available means: the fragments of attention that become available through certain kinds of tasks, reading that reminds me how words make worlds that connect us, and being with the writing in whatever small ways I can.

Are you writing now, dear reader? How?

—

NANCY REDDY is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review, Pleiades, Blackbird, Colorado Review, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere, and her essays have appeared most recently in Electric Literature. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University. She’s working on a narrative nonfiction book about the trap of natural motherhood.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)