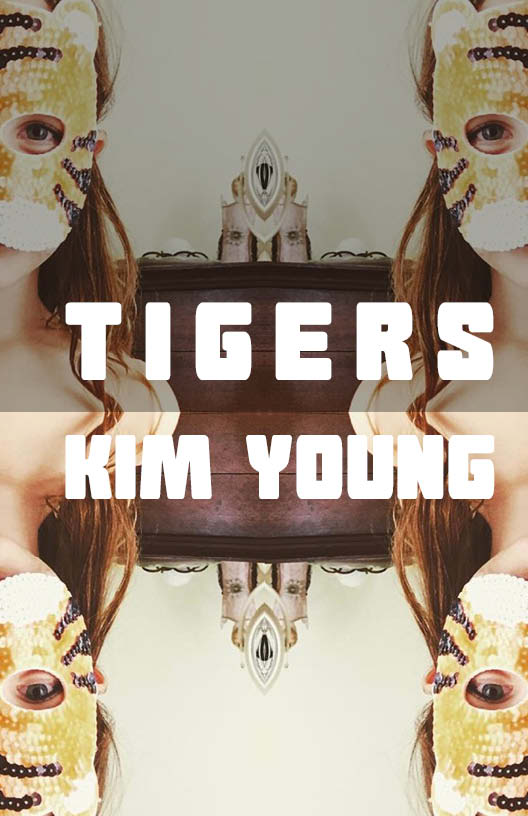

Shelby Handler, an incredible part of our PANK Family, sat down with author Kim Young to discuss her book of poetry, Tigers.

INTRO: Tigers is an exploration of a series of mutigenerational landscapes of the feminine–female adolescence, womanhood, motherhood, and personal revelation. Where the traditional coming of age story moves from “innocence to experience,” Tigers moves, through the excavation of trauma, addiction, recovery, adolescence, parenthood, and punk rock, from the ignorance and misunderstanding of a youth’s misbegotten “toughness,” into a turning inward toward tenderness and resilience—toward, in essence, what it really takes to be mature, “tough,” and–tigerly. With a principle focus on the dangers threatening girlhood, this book examines not merely the threat of degradation and assault, but, more deeply, the squandering of love through ignorance and inattention. Tigers here surely serve as symbols for such outward and inward threat, but also as a sign of the mature and tender maternal toughness of youth-grown-wise through trial and reclamation.

SH: There are many lush and haunting layers to this book: the tigers, the mother ghosts, the marriage fragments, the “directional headings” that orient each section. For me, they created a chorus of different voices and conversations, across time and space. They orchestrated tensions between the mundane and the sacred, the living and the dead, creatureness and humanness, predator and prey. How did you come to some of these different threads? When and how did you know they all needed to ring together in Tigers?

KY: I started the poems that make up Tigers after the birth of my firstborn and those early drafts initially wrestled with the more apparent theme of danger—especially given the formative trauma of my sister’s kidnapping and rape that I explored in my first book, Night Radio. The motif of the tiger had been a recurring dream of mine since I was in my twenties. It was about threat—yes—but more about power (in the dreams I learn to pass tiger without it pouncing and eventually I harness the animal and walk it on a leash).

At some point in the writing of the manuscript, I noticed, too, all the other wild animals populating the poems—coyote, deer, raccoon. The urban wild. Fellow feral hearts. As a parent, I was growing increasingly uncomfortable with the role I played in a child’s domestication process: The ways we teach children to become social humans who don’t stick their toes in the oatmeal. My role as a parent raised questions for me about all that’s sacrificed in the process of maturation and how we spend so much of our adult lives trying to recover the wonder and wildness that we train out of children.

I could see this, too, in the poems that were related to my adolescent self—that loaded girl living in her car with her shaved head and hairy armpits. She had something to tell the mother I had become. And so the idea of tiger kept opening up for me, kept yielding meaning, but at its core is what you are pointing to: a sort of tension between the past and present, the wild and tamed, predatory and prey. The threads you mention are ways for the poems to investigate moral complexity, states like shame, grief, ferocity, and tenderness. And they’re also a way to speak to what’s hidden, or what stands behind. I was interested in exploring that feeling, the unseen, the more unruly and concealed parts of the self.

SH: On the topic of the directional headings, I love that they basically make the book a compass, something that must be navigated by circularly: East, South, West, North, Center. In that way, I felt like Tigers resisted and played with chronology in fascinating ways. Though the collection thrums forward and has momentum, it simultaneously pushes against linearity. Inside each section, we move across generations, across eras of the speaker’s childhood, coming-of-age, recovery and adulthood. Quite literally, present and past tense are packed tightly together in the poems. For me, it brought up the ways that healing, particularly through violence, addiction and patriarchy, is non-linear, intergenerational, messy. How were you thinking about chronology in writing and ordering the book? Did you produce in a similarly non-linear fashion or was there any pattern in their original creation?

KY: A central project of the book is a retrieval of the non-rational, the unbound—a part of the self that is often neglected in a world the overly values productivity. Inhabiting that space meant that many of the poems resisted notions of linearity, progress—stories that are told as a straight line moving through time.

Also, I think of that line in Richard Rodriguez’s essay “Late Victorians” where he writes: “I do not believe an old man’s pessimism is necessarily truer than a young man’s optimism simply because it comes after. There are things a young man knows that are true and are not yet in the old man’s power to recollect.” And while I’m not necessarily exploring Rodriguez’s notions of optimism and pessimism in Tigers, I’m definitely interested in what my younger self knows that my older self might be trying to reclaim. The book is very much a project of going back to find the wisdom that might’ve been concealed or overlooked. And I think of reunification and retrieval as circular processes—maybe a spiral?

I’ll say, too, that the prose poem has been a generative and spacious form, one that works against chronology, where I’ve enjoyed the ability to move more quickly between past and present, between interior and exterior, a form flexible enough to carve out the interior thoughts of the speaker along with dialogue, newspaper headlines, song lyrics, and other layers of text.

SH: Ok, not to just keep talking about the directional headings, but hey, you give a queer witch a book that is structured with feminist witchcraft and this is what you get. Clearly, I’m fascinated by the way they structure the book into five sections, each representing a cardinal direction but also an energy, a power, specifically, the powers to “know, will, dare, keep, change,” in that order. For any muggles out there, these directions are used to “cast the circle” for a ritual, to open the space. How did you come to these as the skeleton for the book? Are the poems themselves rituals, invocations or spells?

KY: Exactly—calling in the directions transports you between the worlds, between all the mundane details of daily life (the freeways, sunburns, and monthly payments) and the shadow world—the great vault, the unknown, the mystery. Most things are not as they seem. And the directional headings hopefully amplify the idea that the poems are spaces where the reader can enter and get a peek behind the veil (as I suppose all poems are on some level).

The directional headings came later in the process of structuring the book (though they were how I was taught to cast a circle back in 1999). As an organizing structure, the directions—with all the connotations associated with each element (water as emotion and intuition, for instance, and air as inspiration, thought patterns, the cerebral) really helped me order and organize the poems and conceptualize how I wanted the book to function as a whole, again resisting a linear narrative that arrives at a destination or revelation. Instead, each section, each direction, is a place for a particular kind of knowledge. Given that this book is dedicated to my daughter, I wanted it to be a, sort of, book of shadows that I could hand down to her. I wanted it to be, not necessarily instructions, but instructive, the way a spiritual text can act as a map for what’s most mysterious.

SH: Part of my fascination with how feminist witchcraft influences your work is because a central interest of Tigers is the delving into the speaker’s ancestry. We see this, in the Mother Ghosts series and beyond. Specifically, you seem to be exploring with what it means to have European ancestry, in Estonia, Hungary, and Ireland, and your investigations are matrilineal, focusing on the mothers and grandmothers who have come before. I’m so curious about this ancestor work, and how it is related to the other threads of the book, the childhood and coming-of-age stories, the tigers, the witchcraft, the marriage fragments. How did those poems come to you? Research, ritual, communication with ancestors, dreams?

KY: I can hear the stories of my mothers and grandmothers, but I have little context to comprehend what they mean. Until I cross the threshold and stand at that age, or, in this case, with a child of my own, those ancestral stories had little significance. The very first poems I wrote came after I entered motherhood. Little by little, I began to understand the strength, compromises, and failures of my own mother and grandmothers in ways that were uncomfortable and profound. Questions of what we inherit and what pass down are central to this book, and I suppose the powerlessness I felt in handing down a certain legacy of suffering to my daughter meant an exploration of ancestry. In many ways the poems came from my ability to recognize the ancestral stories I had be carrying all along in new ways.

SH: To extend the last question even more, I really appreciated the poems where you are grappling directly with whiteness and complicity with white supremacy in your family and yourself. As a fellow white poet, I believe it’s vital for us to do this work of unearthing complicity, reconnecting to ancestry lost in assimilation in our creative work, and of course, moving power and heeding the calls of BIPOC movement leaders. I’m curious how you’re thinking about contending with whiteness in the book? And is it related to how the book’s speakers are resisting other violences and oppressions?

KY: In a book so concerned with power, it makes sense that I had to at least begin the work of looking at white supremacy and, yes, my complicity in that system. In my case, the intersection between sexual violence and the fact that my father and other men in my family worked in law enforcement, the very people who brutally police and uphold the laws that protect white supremacy, seemed unavoidable. And because my father was an LA cop and because he is a man I love, I have a vantage point into that world that not everyone has. It’s a complex and fraught relationship to power, and I can only think that I would do more harm by ignoring it.

SH: The way you move between different forms on the page is refreshing and dynamic. In Tigers, there are so many different textures alongside one another: prose-block poems, poems filled with gaps and spaces that sprawl across the page, short-lined poems that pull us along slowly, and so much more. How do see these poems singing with each other? Is your generative process different for different forms?

One of my explicit experiments in Tigers was to explore forms that were different from the elliptical, image-laden poems that made up much of Night Radio. I was interested in syntax and repetition, in how to create music with the sentence. I felt drawn to the ways the prose poem contains all the stuff that makes up poetry—image, metaphor, compression, repetition—but is also interested in story-ness. I mean, these prose poems (and the prose poems I most love) still do what poetry does: they create a space for the reader to have an experience, to recover a more complex perceptive kind of knowledge. But there’s also less investment in silence, in the unsaid. And much more investment in velocity. There’s a meat & potatoes feeling to a prose poem—something substantial and filling.

SH: Okay, last question. Do you have any “ghost books” of this collection, as Maggie Nelson calls them? What texts did you “lean against”, or what minds think along with, in the creation of Tigers?

KY: Yes—I love Maggie Nelson’s notion of the “ghost books” and while I don’t think I have necessarily leaned against texts in this book in the same way Nelson describes, I love to think about the contexts out of which we write. I definitely turned to Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, another text that I returned to as an older human and saw with completely different eyes. And there are many quoted lines from Tich Naht Hanh’s writing, the 90s music I grew up with–The Cramps, Bikini Kill, and PJ Harvey. There’s the oral wisdom I was raised on in twelve-step recovery meetings. And then specific texts like Michelle Tea’s essay “On Valerie Solanas” in Against Memoir and poems like Robert Hass’ “My Mother’s Nipples.”

SH: Ok, putting all those books and pieces on my to-read list. Thank you so much Kim for this stunning book!!

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)