~by Randon Billings Noble

Sarah Crichton Books

(an imprint of FSG)

Hardcover $23.00/Paperback $15.00

265 pages

My mother left me her journals, and all her journals were blank.

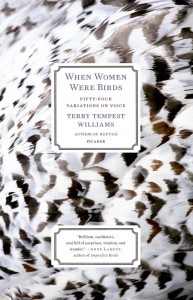

This is the refrain that runs through Terry Tempest Williams’ When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice. The blank journals become other things to Williams over the course of the book: an obsession, an act of defiance, a tease, a palindrome, an awakening, salt, clouds, myth. But they are always stubbornly and irrefutably blank.

I’m glad I read Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place first. Otherwise Williams’ mother would have been as blank as her journals, and I would have filled in a very different person based on what I know about mothers, Mormons and legacy. But perhaps that is part of Williams’ aim. After this shocking blankness, the blanketing silence her mother leaves behind, Diane Dixon Tempest is revealed to us through memory, letters, and story as a deeply loving yet somewhat elusive woman, wife and mother, as well as a catalyst for Williams’ thinking about self-expression.

I get hooked into this unfolding story of the blank journals, stunned by its vast, silent impact. So when the narrative swerves into Williams’ grandmother’s field guides and the sighting of an albino robin I am jarred a bit, but then I remember the book’s subtitle: Fifty-four Variations on Voice, and everything that felt like a vagary becomes vital: the humiliations and triumphs of Williams’ speech therapy, the unheard testimony she gives to Congress, the voices of women she meets in prison, the high cost of keeping silent against a potentially fatal violent act.

Williams weaves together chapters that explore ways of structuring a manuscript, what it is like to almost be a virgin human sacrifice (really!), the secrets of Nushu (a Chinese script used only among women) and the Strauss opera The Woman without a Shadow (called “the Everest of operas”). At times she tells a linear narrative, like the story of when she was teaching biology at an incredibly conservative school and was yanked out class for allowing her students to “swim” around a darkened classroom to a recording of humpbacked whale songs. Other times she veers into poetic fragments, such as when she reflects on physical intimacy: “It is ‘the lover’s discourse.’ What I hide by my language, my body utters. The necessity. The connivance. Only us. The incalculable two. Understanding love as madness. What can be done? We are done. Never.” But all of these styles reveal something about voice – or silence.

After Williams’ mother dies she waits a month before reading her journals. “I opened the first journal. It was empty. I opened the second journal. It was empty. I opened the third. It, too, was empty, as was the fourth, the fifth, the sixth – shelf after shelf, all my mother’s journals were blank.” What follows are six blank pages that give the reader a shadow of the feeling that Williams had: the shock, disbelief and frustration at encountering nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing. Later in the book there is another blank page to show what Williams is unwilling to show. And there are other physical surprises to the book – in its endpapers, in its margins – that I will leave you, dear reader, to discover.

Because this is a book of discovery. Williams finds multitudes of meaning in the blank pages of her mother’s journals and you will derive your own truths from the pages of When Women Were Birds. This book is everything those journals are – an awakening, an obsession; a tease, a myth; an interrogation, a celebration – everything except blank.

***

Randon Billings Noble is an essayist. Her work has been published in the Modern Love column of The New York Times; The Massachusetts Review; Passages North; The Millions; Brain, Child and elsewhere. You can read more from her at www.randonbillingsnoble.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)