~by Thomas Michael Duncan

160 pgs/$11.40

As any restless new parent will tell you, the world we live in is a dangerous, frightening place. Parents are blessed with these beautiful, wailing, flesh-blobs of wonder, and burdened with the task of protecting them, raising them to be good, happy, productive members of society. Is it any wonder why some parents chose to exercise a great deal of control over their children and their environment, to shelter their young from all the apparent and hidden pitfalls beyond the boundaries of the household?

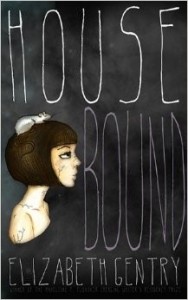

At nineteen, Maggie is eldest of nine highly sheltered children living in a way that borders on quarantine. Each child is homeschooled, recreational time is limited and monitored. The only times the children leave the house are when the older ones run errands and when the entire family visits the library together. The family lives an isolated existence, underlined by the house itself, which is isolated from the rest of civilization by an array of natural features. Housebound, Elizabeth Gentry’s debut novel, begins with Maggie announcing her plans to leave the house to find a job and a new life in the city. This declaration creates a rift between her and the rest of the family, breaking a longstanding spell over them:

“Some time had passed since two complete sentences had been spoken over breakfast that did not pertain to some practical task—an instruction or bid for help. The children shifted on their benches, unable to believe they were witnessing a declaration of intent that even their parents’ refusal could not erase: Maggie had not asked permission nor had she made the announcement in private. She made it in front of all of them deliberately, suggesting that they, too, might seek out something else.”

The following pages account for the final days leading up to Maggie’s departure, during which she is somewhat ostracized by her parents and siblings, and experiences brief tastes of freedom through visits with peculiar neighbors and dining on forbidden sweets.

Gentry presents readers with a world disconnected and isolated even from space and time. The time period is uncertain; it could be 1950, or it could be 2011. The usual hints—current events, technology—are nowhere to be found. A telephone is mentioned briefly, but there is no word on cell phones, computers. The landscape and weather described fits much of the northern hemisphere. Maggie’s destination is always simply “the city.” This squares with Maggie’s point of view, the feeling of being part of a larger yet inaccessible domain.

Surely her controlled upbringing has some adverse effects on Maggie’s development. When she accompanies her father into the city to search for a job, she is “embarrassed to realize that their father did not just retreat from their consciousness every day when he left, the way that characters did when the children set down their books for a break.” Nineteen is surprisingly late for such a revelation. Her social skills are far from par, yet these flaws are countered by positive characteristics. She is intelligent, if naïve, makes up for a lack of ambition with an industrious attitude.

Each passage carries an air of mystery, the sense that a groundbreaking revelation waits in the next page. And perhaps this is exactly how it feels to be a sheltered child venturing bravely into new territory. After all, there is much for Maggie to discover—about the world outside her home, and about the secrets kept inside it. But Gentry chooses not to dole out information in bundles, rather slowly, piecemeal, from different characters with different angles, making the story multidimensional.

The easy takeaway from this novel is that overprotective parenting is a foolish endeavor with impossible expectations. The hard truths of the world cannot be held beneath the surface. Trouble finds a way in. Yet the story stops short of condemning this style of parenting. “Your parents had their own ideas about how to raise you,” Maggie’s grandmother says, “as all parents do.” On the cusp of adulthood, Maggie is a free-thinking young woman, ready to strike out on her own. Far from the most tragic of outcomes.

***

Thomas Michael Duncan lives in Syracuse, NY. His reviews have appeared in Necessary Fiction Reviews, Prick of the Spindle, and Blood Lotus Journal. His online home is tmdwrites.tumblr.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)