Every book I pick up these days seems to be filled with food. Is it I? Is it because I write this column? Is it fiction lending itself to letting people eat and eat and eat? I don’t know. That’s part of what I’m exploring here each month—how do food and writing connect … and why.

Some connections are obvious, of course. Novels are populated with humans and as humans we do a lot of eating. Ritual, celebration. Food binds us to each other.

When I read a scene that has a character eating, I can sneak under that person’s skin; I can be that person. Even though I’m a vegetarian, there I am eating a steak.

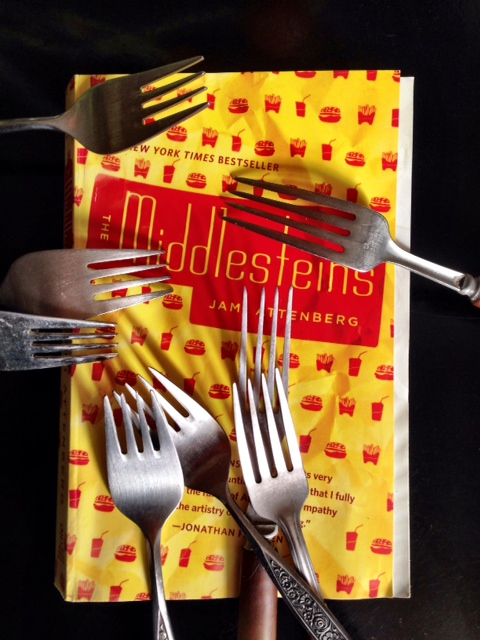

I didn’t come to Jami Attenberg’s novel for the food though. The Middlesteins was included in a Buzzfeed list of “The 24 Most Dysfunctional Families in Literature.” I can’t seem to get enough family dysfunction on my reading list so I tackled the books that I hadn’t yet read.

And, oh boy, The Middlesteins does in fact explore a dysfunctional family that splits apart and patches itself together over a period of years. But what’s really happening is Edie, the family’s matriarch, is eating herself to death. She eats and eats and eats until she dies. This is not an easy book for a food lover to read.

Attenberg reinforces the taut connection between food and love, food and comfort in the first sentence: “How could she not feed her daughter?” (1)

This is Edie’s mom, talking about little 5-year-old, 62-pound Edie Herzen. The moment is set in a stairwell. Little Edie refuses to walk up on her own. Her mother is carrying grocery bags. A tantrum ensues. And we are privy to how the mother is torn between wanting to walk up the stairs and put away her groceries and loving her difficult little girl who is tired and wants to be carried. We learn that this Jewish family understands the history and meaning of hunger. Edie’s father “ate and ate; he was carnal, primal, about food….He had starved on his long journey from Ukraine to Chicago eight years before, and had never been able to fill himself up since” (2).

The moment escalates when a bag rips and a can of food smashes little Edie’s fingers. Everything in this first chapter funnels into this defining moment: “Her mother sat there with her arm around her daughter, until she did the only thing left she could do. She reached behind them on the floor and grabbed the loaf of rye bread, still warm in its wrapping paper, baked not an hour before at Schiller’s down on Fifty-third Street, and pulled off a hunk of it and handed it to her daughter…” (6).

I love this moment. I can smell the bread—I can imagine its texture as the mother grabs the crust and pulls, brings the chunk of warm bread to Edie’s mouth, which opens “like a newborn bird.”

There’s passion here. And love. And certainly a kind of compulsion to ease and please through taste.

This compulsion continues for Edie as she heads into her life. She hardens, searches for love, and loses her parents who seemed to have a key to something in her, a key they took with them. And so Edie’s compulsion grows. She reaches 210 pounds. She eats with her two little children, Benny and Robin, their McDonald’s tray loaded down with Big Macs and Happy Meals and fries and cookies. In this scene Edie circles around what draws her to food when she muses about six-year-old Benny’s lack of concern for it: For little Benny “It was not about taste. It was about some sort of affection or association with a memory, she suspected. Like, maybe she had given him macaroni and cheese on the first cold day of the year and it had warmed him up so beautifully that he craved that same sensation on repeat” (90).

Edie is a charming, flowing character. The family is filled with distinct, quirky people with cravings large and small. But everything escalates. Edie’s husband leaves her, her children grow up; she tops 300 pounds.

She has a fast food route she hits one gleaming primary-colored drive-thru to the next in a series of hours. Her daughter-in-law trails her, mouth agape. Edie’s eating is epic, and she doesn’t want to stop. There is a deep, heartbreaking compulsion in her to eat as if she’s digging to find this one thing in her past, giving up the potential of the present. And perhaps it is that moment on the stairwell with the steaming loaf of rye. She’s eating to find that exact love again.

Attenberg, Jami. The Middlesteins (Grand Central Publishing, 2012).

***

Sherrie Flick is author of the novel Reconsidering Happiness and the flash fiction chapbook I Call This Flirting. She lives in Pittsburgh.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)