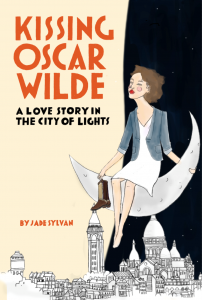

Write Bloody Publishing

160pages, $15.00

Review by Max Vande Vaarst

It feels as though nothing could be more Millenial. What better emblem of the “Me Me Me” generational tagline posited by Time Magazine than a memoir written by an author barely on the cusp of thirty, a novelized account of a nascent artist’s ramblings through France and her search for the self in the City of Lights? Yet to fellow members of a debutante generation now nearing the end of its post-recession cotillion – this brief, shared moment of youth, opportunity and national spotlight – Jade Sylan’s dazzling new work Kissing Oscar Wilde can seem, if anything, overwhelming in its urgency. In many regards, it is no more a memoir than a eulogy to one’s twenties, and a prayer for the long, unknowable period of adulthood ahead.

At the center of the novel is Sylvan herself, an up-and-coming poet and all-purpose bohemian presently living in Boston. It is sometimes unclear to what extent Sylvan the author resembles Sylvan the character, a self-styled androgynous, polyamorous, bisexual Dylanphile who wears her wavy knots of hair in perfect mimicry of the folk legend during his mid-‘60s Don’t Look Back days. Perhaps there’s no point in attempting to separate the two. Vonnegut was correct in surmising that “we are what we pretend to be,” and this impulse for projection has never been truer than of artists in the internet age.

Like young Dylan with his heroes Guthrie and Rimbaud, Sylvan is enamored with imitation. She departs the Midwest for Boston because its literary scene seems “the closest to the Parisian Lost Generation.” She studies Patti Smith’s own memoir Just Kids for lifestyle advice as though it were a teenage fashion magazine, and abandons her birth name in favor of something new, a name made beautiful by its sense of naturalist romanticism and, more importantly, by its “slant rhyme with Dylan.” Sylvan the character is as much a product of fabrication as memory, which Sylvan the author acknowledges when she notes, “When I write about myself in France, I feel like I’m creating a character from nothing. I’m doing it because I have to in order to tell a story.”

There’s an admirable sort of immaturity in this – all artists must of course begin as copycats – though at times Sylvan’s single-minded desire to ‘look the part’ can become grating. I was especially perplexed by her insistence on making art only in “a real city on a coast,” having myself escaped the New York area in favor of first Sylvan’s native state of Indiana and then later on Wyoming, ostensibly in search of the “true” America. In this we find another commonality linking idealistic creative types of all stripes: the belief that Authenticity exists, yet is always in hiding someplace else.

The events of Sylvan’s travels in Paris make for a somewhat interesting travelogue. Her descriptions of places like the Reims Cathedral and Oscar Wilde’s own Père Lachaise Cemetery are as vivid and evocative as scenes from an old foreign film. A near-romance with a cowboy boot-wearing local named Adélaïde is both charming and a little sad, the sort of friendly, superficial crush that can only unfold within the limited window of international adventure. True to form, Sylvan imagines a timeline in which their potential romance unfolds like that of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas.

Try as Sylvan does to add heft to her tourism, it is her internal world that drives the novel and controls its form. The text often shifts with Sylvan’s mood, transforming from straightforward narrative to structures as diverse as a documentary list of former lovers, full-text poems (including the lovely title piece, “Kissing Oscar Wilde”) and a stage drama-style conversation between the character Sylvan and her imagined audience. These last scenes are among Sylvan’s most powerful, and her most naked.

“Thou art not fucked-up. Nor art thou special. Thou art like everyone else,” the audience states in a mock Elizabethan dialect. This is a hard truth for an educated Millennial, to understand the smallness of your reality, that your talent only goes so far. “Now telleth us, what wantest thou?” they ask.

“To connect with people,” the character Jade responds, “…To be fully human and have people see me be human…to not be alone.”

This is remarkable introspective writing and an astute examination of the creative drive. In traveling to Paris, Sylvan participates in the classic tradition of ‘finding oneself,’ yes, but vitally, she also comes to find Art, to know that those we call artists in the end are not the most special, nor the most talented, but they for whom art “is the only alternative to death.”

It’s a message bound to resonate with any young artist, and a message that makes Kissing Oscar Wilde well worth reading.

***

Max Vande Vaarst is a maybe possibly someday up-and-coming writer of imaginative fiction and the founder of the online arts journal Buffalo Almanack. Max’s work has been featured in such publications as A cappella Zoo, JMWW and Jersey Devil Press. He currently resides in the Denver, Colorado area and can be found online at www.maxvandevaarst.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)