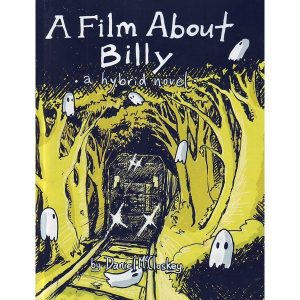

Six Gallery Press (distributed by Birdcage Bottom Books; reprint distributed by Small Press Distribution)

248 pages, $12

Review by Rachel Mennies

Collin, the teenage protagonist in Daniel McCloskey’s comics-prose hybrid novel A Film About Billy, has a movie to make about his dead friend William, and a seven thousand dollar grant from the enigmatic Mint Foundation to complete it. Billy jumped in front of the train tracks near a military base in Canyon City, Pennsylvania, not far from Pittsburgh; his body takes the blow so hard that his friends find pieces of him for miles up and down the tracks—a piece of his long black hair, a discernable shard of his skull. McCloskey’s first book follows Collin, the narrator of the book’s prose sections and the creator of the documentary film represented in the book’s comics frames, through what first appears to be the ordinary process of mourning a sudden loss, and later manifests as a wildly dystopian tale of an international suicide epidemic and a government plot far more bizarre than anything Collin—or the world—could have imagined.

At the center of this book live teenagers: artists and filmmakers and gamers, agents of action, prey to depression and drugs and ennui and suicide, and—most emphatically—the book’s emotional and intellectual centers of integrity. Many of the enduring adults in A Film About Billy—warped scientists, corrupt military personnel, and absent (or present, sometimes for the worse) parents—perpetrate most of the book’s evil. Collin and his friends first unite in the wake of Billy’s death, only to splinter apart as suicide and unrest overtakes Pittsburgh. McCloskey renders these protagonists most thoroughly and tenderly as the book opens and the story of Billy’s suicide unfolds—as we “watch” the first few frames of Collin’s documentary, where Billy lives, as teenager, forever.

Seeing Billy at once dead and alive, thanks to the novel’s hybrid mode, captures both the sharp grief of those left behind after suicide and the deceptive nature of mourning and memory: how the dead remain with the living after loss, sometimes as a gift, other times a plague. As editor of the documentary, Collin notes “no matter how I put together the story, my friend died: Kids struggle in an oppressive environment, and my friend dies. A group of druggies meets the popular girl who ends up liking them, and my friend dies…I didn’t want my friend to die. I wanted my friend to live, but how could I make him live when he was dead?” This trap also snares the reader: Billy appears and disappears throughout the novel, as do other characters later lost to the suicide epidemic, leaving Collin and the rest still alive to reckon with the cost of living in the wake of so much easy-seeming death.

While A Film About Billy’s setting expands and sprawls as the plot boomingly accelerates in the book’s later half (elliptically: a whole bunch of crazy shit happens, and fast), McCloskey sets the book’s “home” in Pittsburgh: a city of sunrise-watching roofs, truck-graveyard hollows under concrete monolithic overpasses, and streets that drop off the face of the earth deep into the city’s twisting inclines. It’s here that the seeds of both Collin’s film and A Film About Billy itself germinate into fantastic tragedy, eventually merging comics-panel and prose to reveal the secrets of the source of both Collin’s grant and the suicide epidemic more broadly.

As the documentary transitions from telling the story of Billy to telling the story of the entire lost world, it—and the book as a whole—never loses sight of its ultimate driving narrative: that, as a frame from the film tells us, “Teenagers, by their very nature, are beings of change.” Even in the midst of the worst-possible scenarios both global and personal, it’s youth who hold the keys to solving crisis and sorting grief, and it’s their one-foot-in-childhood, other-in-adulthood lens on the world that grants them this particular power and vision to effect change. A Film About Billy, then, tells the story of not just grief and corruption but also one of ongoing evolution: that which we all must push through to become whole, and adult, and truly and entirely—while we still have the time—alive.

***

Rachel Mennies is the author of The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards, winner of the 2013 Walt McDonald First-Book Prize (Texas Tech University Press), and the chapbook No Silence in the Fields (Blue Hour Press). She is a member of AGNI’s editorial staff.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)