Harper Perennial

236 pages, $14.99

Review by Megan Culhane Galbraith

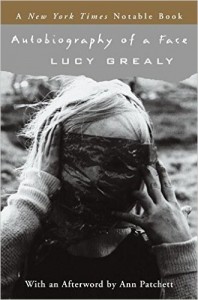

Just when I needed it, when I’d planned to write about Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy, for “Books We Can’t Quit,” the book quits me. I couldn’t find my 1994 edition in my own bookshelves (had I loaned it to someone?), I went to the Saratoga Springs library and it was listed as “lost” in the catalog. I found one copy, a reprint, and the last one on the shelf at a local, independent bookstore. How, I wondered, could I have allowed one of the most important books in my life to vanish?

Was this a metaphor for what Grealy’s book has meant to me? Why has it haunted me since I first read it in 1994?

Autobiography of a Face is an excavation of Grealy’s soul. In it, she dissects the pain endured by multiple surgeries to her face as a result of a Ewing’s Sarcoma discovered when she was just nine years old. Skin grafts, bone grafts, tissue expanders, chemotherapy, and radiation, these are all physically painful, but it was the emotional agony that resonated with me: her throbbing, metaphysical pain.

Autobiography is a memoir about loss on multiple levels, but for me back then, it was simply about girlhood; the insecure, low self-esteem, failer-of-every-Presidential-Physical-Fitness-Test-ever, misfit kind of girlhood I’d experienced too. I’d found a kindred spirit. I’d found myself in Lucy Grealy’s sentences.

When Autobiography of a Face was published in 1994, I was 23 years old and flailing around in my own little post-college world. I don’t remember what drew me to the book, but I’m pretty sure it was simply the intriguing title and the prologue, “Pony Party.”

My 23-year-old self identified hard with Grealy, who to me at the time was just another Irish girl who loved horses, David Cassidy, and who was made to feel a spaz in gym class, or inferior for being different because of the way she looked.

I was relentlessly made fun of in school for my crooked mouth. The boys called me ‘Sidecar,’ elbowed me into lockers, and threw carrot sticks at me on the school bus. Years later, I would come to find out my mouth crookedness was a direct result of a traumatic high forceps delivery in the charity hospital where my birthmother had given birth to me. I had been adopted and was trying to come to grips with what that meant and who I really was. Here was Grealy who seemed to be asking similar questions about her own identity and self-image. I felt like we were soul mates. I imprinted myself all over her. Maybe we were secret sisters, I thought, I was a spaz too!

I now see my connection was so strong because of her ability to form clear, honest, unsentimental, probing sentences. This one, in particular, has stayed with me:

Anxiety and anticipation I was to learn, are the essential ingredients in suffering from pain, as opposed to feeling pain pure and simple.

At the time, I understood this as a truth, but I didn’t know why. Now I see how carefully Grealy was dissecting her own emotions. Now too, I understand how long and hard she may have labored to write that single sentence: To distinguish between “suffering from” and “feeling” pain.

But I felt, and still feel, she was the sister I’d always wanted. I didn’t yet know that my longing was because I hadn’t pinpointed my own feelings about my very different suffering. I was still years away from forming even the questions I needed to ask that would untangle my emotions about having been adopted. I didn’t yet know the language of it. But here was Grealy, showing me the way before I knew how. In hoping she could have been my sister, I now know that I was trying to identify a family for myself, a place to belong. I felt I very much like I belonged in her book.

When Grealy’s book went missing, I felt I’d lost a piece of myself. Sure I bought another copy, but I had wanted to hold in my hands the same book now that I had then. I wanted to see if 23-year-old me had written in the margins and, if so, what I’d thought back then so I could compare it to now.

As a young girl I always felt I was late to the dance, the last one to know something. My mother had to once forcefully tell me, “People don’t always mean what they say, Megan.”

My younger self puzzled over that statement, couldn’t square it. How could people not mean what they said; they’d said it? The saying implied ownership and ownership implied meaning, didn’t it? If I couldn’t believe the things people said, how could I believe anything?

These are epiphanies I shared with Grealy after reading passages like this one: “More than the ugliness I felt, I was suddenly appalled at the notion that I’d been walking around unaware of something that was apparent to everyone else. A profound sense of shame consumed me.”

We were David-Cassidy-loving spazzes. We were kindred spirits and even though she chose to quit this world, or it quit her thanks to heroin, I will never quit this book.

I used to think truth was eternal that once I knew, once I saw, it would be with me forever, a constant by which everything else could be measured. I know now that this isn’t so, that most truths are inherently unretainable, that we have to work hard all our lives to remember the most basic things.

One sentence grafted to the next and to the next. Stitch by stitch Grealy led me forward through her life’s pain at every turn and she healed me. Unlike the multiple grafts on the bone of her jaw and the skin of her face, the truth in Grealy’s words will not dissolve, and will not disappear. The beauty about her sentences is that they can live forever.

***

Megan’s work is in ASSAY, Literary Orphans, Hotel Amerika, Consequence, drafthorse, and elsewhere. She was a finalist for AWP’s WC&C Scholarship judged by Xu Xi, and a Scholar at Bindercon. She is writing a collection of essays titled, The Guild of the Infant Saviour. Connect @megangalbraith, at megangalbraith.com and at The Dollhouse.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)