Rita Banerjee’s essay in three parts, “The Female Gaze,” is an excerpt from her memoir and manifesto on how young women of color keep their cool against social, sexual, and economic pressure. In her essay exploring the female gaze, female agency, and female cool, Banerjee asks:

What if women, especially women of color, were the progenitors of cool? That is, did women have to cultivate their own cool—their own sense of style, creative expression, and coldness—in order to survive patriarchy across millennia across cultures? If the male gaze aims subordinate and colonize, what does the female gaze, tempered by cool, desire? What does the female gaze cherish or hold dear? If a woman were fully aware of her gaze, would she use it to objectify and colonize, or could her gaze destabilize and decolonize?

Photo still of Zowa and Ariane, a French couple from Burning Down the Louvre (2022), a documentary film about race, tribalism, and intimacy in the United States and in France.

III. I see you seeing me

In the line outside of the Beauté Congo exhibit at the Fondation Cartier, Michael digs into me.

“Your stance, it’s always political, political, political.”

His hands make a gesture like he’s solving a Rubik’s Cube.

“You’ve got a 30,000 foot aerial view on things, Rita, you’re never are going to get your hands dirty that way.”

My lips press together into a tight smile before I speak.

“And what about your view?” I try to parry, “Is everything in the world reduced to something that’s just Oedipal? Isn’t your gaze, in essence, Freudian?”

I avoid his eyes and know that I’m not saying what I really think. I’m afraid to say what I really think in front of him. What I want to ask is: isn’t everything you talk about invariably and essentially about sex?

Michael’s eyes are two dark missiles pointed at me. He aims and doesn’t look away. Our arms race occurs in silence. The silence stretches into infinity.

He leans closer. My heart speeds.

“Exactly,” he says with a half-smile as if he can read the thoughts I am afraid to articulate.

* * *

In Town Bloody Hall, Germaine Greer engages in a battle of wills and wits with Norman Mailer as he argues that men are merely passive slaves to women, who are the ones who really hold power, in The Prisoner of Sex.

The debate takes place at NYU in 1971.

In the film, Mailer introduces Greer as the “lady writer” from “England,” although Greer is clearly exhibiting an Australian accent and despises the term “lady” to qualify anything.

Her fur stole drags on the floor as she responds to Mailer:

“I turned to the function of women vis-à-vis art as we know it. And I found that it fell into two parts. That we were either low, sloppy creatures or menials, or we were goddesses, or worse of all, we were meant to be both, which meant that we broke our hearts trying to keep our aprons clean.”

Mailer doesn’t look up, Greer doesn’t pause:

“I turned for some information to Freud. Treating Freud’s description of the artist as an ad hoc description of the psyche of the artist in our society, and not in any way as an eternal pronouncement about what art might mean. And what Freud said, of course, has irritated many artists who’ve had the misfortune to see it: He longs to attain to honor, power, riches, fame, and the love of women but he lacks the means of achieving these gratifications.”

Greer pronounces the words and the camera settles on Mailer’s worried face. The audience chuckles at his unease. She does not stop:

“As an eccentric little girl who thought it might be worthwhile, after all, to be a poet, coming across these words for the first time, was a severe check. The blandness of Freud’s assumption that the artist was a man sent me back into myself to consider whether or not the proposition was reversible. Could a female artist be driven by the desire for riches, fame, and the love of men?”

* * *

Throughout my MFA program and grad school days, I had a batik tie-dyed image of Saraswati on my bedroom wall. She was strategically placed to hover over my writing desk at all times. Because goddesses were part and parcel of the modern Bengali imagination, and because my life couldn’t get any more hippie.

Several years later, when I moved to Munich, I started to teach creative writing classes in town at a local English-language bookstore called The Munich Readery. One of the first classes I taught involved “evocative objects.”

The room was packed. With thirty students or so. I asked them to come up to the stage, one-by-one, and pick up an object from the table that they found strange and fascinating, and write a lyrical, essayistic, or narrative piece that spoke to the object or spoke from it.

Emily Phillips, an expat African-American poet and dramatist living in Munich, came up next. She took her time rummaging through the objets d’art, and chose at last a small object gleaming silver, and then sat down to write an essay about India and the recent rape of Jyoti Singh Pandey in Delhi and her fears of traveling to Asia all alone. As I walked around the room and listened to her read her piece aloud, I found myself wanting to reassure her that women could not only combat the male gaze but could subvert male violence, too.

But the conviction in my voice faltered as I made my way up to her. I scanned her face and saw her eyes flash with confusion, hope, disbelief, worry, and rage. What could I say in reassurance to those eyes? Was there any society on earth worth defending that only saw women as bodies, as anonymous vessels for male enjoyment and cruelty?

“What do you have there?” I asked, avoiding her glance, and peeking over her notebook at what she held in her hand instead.

“It looks like it’s a seated woman wearing a machine gun,” Emily answered.

“A machine gun?”

“Yes,” Emily elaborated on the story of the female figure. “It looks like she’s holding a machine gun in her hand and swearing a chain of bullets.”

“Oh,” I did a slow double-take and let out a breath, “that’s Saraswati. She’s the goddess of the arts.”

* * *

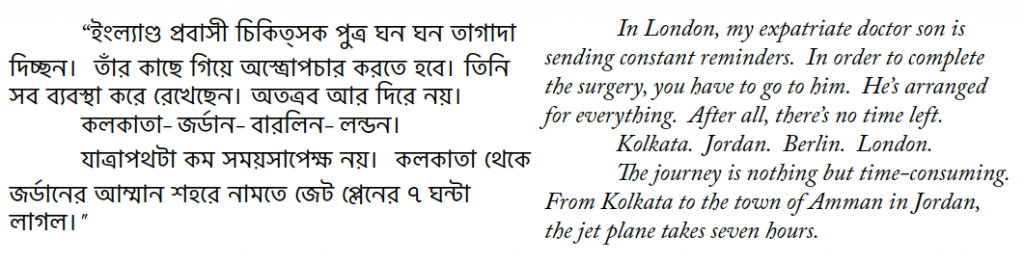

In Cambridge, in August, when the sun dapples through the old lindens and wisteria and makes everything seem like a mid-summer night’s dream, Michael and I find ourselves interrupted. We are shooting a scene for our documentary film on race and racism in Paris. We are laying down the narration and plot point B for the film, when our film crew revolts.

Two members of the camera crew, two young men, both in their early twenties, take over our mics and seats. They push us out of our chairs and literally off the stage.

“You’re not commenting on the action happening on the film reel behind you,” a Harvard undergrad exclaims, fanning a hand through his dirty-blonde hair. “I mean look at the cops hitting black protestors, that’s racist, right?”

In the back of the room, behind the rolling cameras now, Michael and I watch and listen.

“I feel complicit,” says the other young bespectacled man, also with blonde hair but tinged with gray. “I feel like I’m part of some sort of psycho-sexual drama.”

My ears pricked. In the dark, Michael grips his paper coffee cup and wrings it, as if it were the neck of an undergrad.

“I mean, Rita,” the tall, blondish undergrad continues, now addressing me, “you said yourself that you’re a fan of Beauvoir. But as Michael mentioned, when one becomes a woman, one becomes both subject and object. To not recognize that one is an object would be to deny oneself the eroticism of objectification.”

Excuse me, I think, but don’t get a chance to counter before he continues.

“So we think that you and Michael should explore that space. There’s some sort of dynamic building between you. So why not go for it? Why not become a woman, Rita?”

Excuse me?

The twenty-one-year-old issues his dare and stares at me, off-screen. His more nervous and thoughtful, bespectacled friend does the same. Michael barely turns my way, but I can feel the tension radiating from every part of his body. I am surrounded by the ferocity of three male gazes: three white male gazes: three white male cis-heteronormative gazes. And all these gazes are asking me to do is become the thing I fear most: a woman.

You’re standing on my neck.

* * *

Bengali culture is full of ghosts and goddesses. Sometimes, they are even the same. Every autumn, from mid-October through February we would celebrate puja season in New Jersey. Puja, or an act of ceremonial worship, always appears to center on the honor and reverence of goddesses.

The season always began with a puja to Durga, the wife of Shiva, a woman warrior and fierce mother figure, who was the only god with enough chutzpah to defeat the buffalo-demon Mahishasura. She could do this, in part, because she was female. From the feminine, came her strength.

And her desire, too. Because Durga soon transformed into Kali, after that first death. Once she tasted violence, Kali could not get enough of it. She danced around the world naked, covered in garlands of her victims’ severed heads, hands, and other trophies of war. Only when she stepped on the body of her husband, Shiva, did her rampage stop. The wife’s foot on her husband’s body. The ultimate patriarchal mark of dishonor.

Later in November, during Navaratri, there’s the celebration of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity. At night, wax candles in copper lamps are lit to illuminate her way into each home.

And finally, in February, Saraswati, the goddess of learning, knowledge, elocution, and the arts is celebrated. She is seated beside her owl or swan. She often has a quill in her hand, or often is depicted playing the sitar.

Goddess worship is innate to Bengali culture. Bharat, itself, is often referred to as “Mother India” in many local tongues. In Hindu and Jain cultures, the cow is not holy, but she is, of course, female.

Of his kinsman, Rabindranath Tagore once wrote, “Bengali mothers don’t raise men, they raise Bengalis.” It was meant as a form of barbed criticism but was received as praise by his native audience.

Over coffee one day, my mother, Gargi, the scientist and the philosopher turns to me, “Do you know that the Sanskrit word for power is feminine?”

“You mean Shakti?” I ask, thinking the term connotes strength.

“Yes,” she answers, “shakti is power, absolute, divine. Without shakti, there is no human power. Without feminine power, there is no masculine.”

I pause and smile, “Then how do you explain the patriarchy?”

* * *

In Cambridge, the day after our shoot ends, Michael asks about the camera operators. Both men were blonde and blueish-eyed, but he inquires about the young man he knows personally. The tall one. The one who doesn’t wear glasses. The one with the roving eyes. The one who suggests the crew should step out, the cameras keep rolling, and Michael and I make out on screen. The one whose gaze cuts me like a knife.

“Do you find him beautiful?” he almost whispers. We are alone in the faculty cafeteria, staring at my computer screen. We watch the video footage from the day before as the two boys overtake us on stage.

Michael sounds thoughtful and tired.

He might as well be asking: Do you find me beautiful?

My eyes rove over his nervous hands, his cool glasses, his face. When they finally meet his, it’s a union of hazel against deep brown. He’s looking right back at me. His eyes are softer than they ever should be. They catch light. So I whisper back:

“Who says the eye loves symmetry?”

Rita Banerjee is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing and Co-Director of the MFA in Creative Writing and Publishing program at the George Polk School of Communications at Long Island University Brooklyn. She is author of CREDO: An Anthology of Manifestos and Sourcebook for Creative Writing,Echo in Four Beats, the novella “A Night with Kali” in Approaching Footsteps, and Cracklers at Night. She received her doctorate in Comparative Literature from Harvard and her MFA from the University of Washington, and her work appears in Hunger Mountain, Isele, Nat. Brut., Poets & Writers, Academy of American Poets, Los Angeles Review of Books, Vermont Public Radio, and elsewhere. She is the co-writer and co-director of Burning Down the Louvre (2022), a documentary film about race, intimacy, and tribalism in the United States and in France. She received a 2021-2022 Creation Grant from the Vermont Arts Council for her new memoir and manifesto on female cool, and one of the opening chapters of this memoir, “Birth of Cool” was a Notable Essay in the 2020 Best American Essays.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)