(Note: Having not written at the [PANK] blog for nearly a year, I apparently thought the best way to make up for that absence would be to stuff an entire year’s worth of posts in one. I am definitely doing the Internet wrong. Also, this is failed essay is something of a throwback to the two failed essays posted here at [PANK]. I did say “failed.â€)

Trinh T. Minh-ha, “All-Owning Spectatorship”:

To say red, to show red, is already to open up vistas of disagreement. Not only because red conveys different meanings in different contexts, but also because red comes in many hues, saturations, and brightnesses, and no two reds are alike. In addition to the varying symbols implied, there is the unavoidable plurality of language. And since no history can exhaust the meaning of red, such plurality is not a mere matter of relativist approach to the evershifting mores of the individual moment and of cultural diversification; it is inherent to the process of producing meaning; it is a way of life. The symbol of red lies not simply in the image, but in the radical plurality of meanings. Taking literalness for naturalness seems, indeed, to be as normal as claiming the sun is white and not red. Thus, should the need for banal concrete examples arise, it could be said that society cannot be experienced as objective and fully constituted in its order; rather, only as incessantly recomposed of diverging forces wherein the war of interpretations reigns.

Seeing red is a matter of reading. And reading is properly symbolic.

Recently I’ve been thinking about the color red. It started, in a way, by reading Derek Jarman’s essay “On Seeing Red,†from his book on color, Chroma. But what held me, reading Jarman’s essay, was his mention of eczema. I’ve written about sickness and eczema here at PANK in the past, but Jarman’s essay, in connection with various current political events, made me feel that I needed to write about it again. Feel it again.

Jarman:

I’m coming back from the blast furnace of St. Anthony’s fire, an eczema which turned me red. Violent red soreness. I turned almost purple. My skin no longer welcomed the world, but shut it out. I was in the solitary confinement of the senses. For two months I could not read or write. Work stopped on this book. The red eczema spreads across my face. ‘Where have you been on holiday?’ passers-by asked. A short stay in hell.

Skin that no longer welcomes the world; yes, that’s right. But it’s more than that. As an eczematic person you no longer welcome the world, but at the same time, in spite of yourself, you become hyper-porous to the world, excessively open, flayed, (hyper-hospitable? eczematic ethics? who or what is the eczematic other? what about the self-othering that happens in illness; how many times did I weep to my husband F., “I’m trapped in this skin, my body isn’t mine, why is it like this, why still, why always, don’t understand, it’s beyond me, what is it reacting to, what does it want, why, can’t, can’t?”).

For Jarman says the skin shuts the world out, but is that so? Or do you shut the world out because of your skin; does your skin shut you out of the world; does the world shut you up into the world of your skin? Is the eczematic a shutting out of the world at all, or is it in fact a radical irrupting into the world, and a radical irrupting of the world into the body? A visceral mutuality and exchange between the social and the biological, the political and the personal, between two sicknesses that are one sickness. The biopower of sickness. Twenty-first century immunology: the place where the world becomes ever more intolerable, while forcing our bodies to tolerate it–and the place where we stop being able to tolerate it.

No, what am I saying? It’s not just the twenty-first century. Immunology has always been about this. About the red no of the red blood. About saying, often without being able to say it: I can’t take this.

*

Eczema: 1753, from Gk. ekzema, lit. “something thrown out by heat,” from ekzein “to boil out,” from ek “out” (see ex-) + zema “boiling,” from zein “to boil,” from PIE root *yes- “to boil, foam, bubble.”

Boiling up and boiling over. What boils me up. Someone like me. Jarman knew what it was to be in a sick body, a fragile/frangible body, a body whose particular sickness was also tied to a politics of what it means to be “healthy” in this world. The shitty world tells queer people, poor people, people of color, that they’re sick, that their lives don’t matter, that their lives don’t even register, that they should die, that they’re already as good as dead. And they get sick and die.

Boiling up and boiling over. All the libidinal forms of arson. Because a riot, too, has an eczematic (anti-)logic (better to say an eczematic spirit? an eczematic force? is an eczematic phenomenon), and not just the obvious “revolutionary red” thing. Particularly the part that always confounds and repells journalists in mainstream media: “why are they destroying their own neighborhoods, burning their own cars,” etc.? The “looting,” the attacks on private property and businesses (which is to say: direct political action, calling out of state-corporate power, spontaneous re-redistribution of wealth, rupture of the embodied public into the formerly public, but now hyper-privatized, sphere–contemporary urban portrait around the world now is a property development’s 3D mockup of the luxury flats they’ll build after they’ve turfed out poor local residents, no one there but a hologram of a young photogenic couple with their two young photogenic kids, one a toddler, one a bit older–obviously they all have smooth and healthy skin–pointing vaguely at a fountain or a well-mown lawn, the “communal gardens” of real estate ad copy, faux-communal gardens instead of commons)–these, the conservative journalists and soldiers of neoliberalism found easy to square away with their pan-criminalizing hoodie paranoia, the menace of “feral youth,” etc. But in L.A. in 1965, 1992, in Paris in 2005, in Brixton in 1981 and 1990, in Brixton and Broadwater Farm in 1985, in London in 2011, people still asked: why do people set fire to the places they live in? (The skin you live in; what if you can’t “love the skin you’re in,†as mass advertising insists you must?) What do you have, to burn against the corporate state, when the corporate state owns everything, including you, your body, your life?

No, we have no “cure” for eczema; most allopathic doctors do not know (are not paid to know) what causes it, and generally only give corticosteroid (immunosuppressive) medication to treat (repress) the symptoms, at varying strength levels depending on the severity of the case. Think of the water cannons used on protestors around the world. You’re inflamed and they douse you. That’s all. Why are you on fire? This question, not to be answered. Why do you get sick? Why do you burn? Why do you want to die? What are all the material and immaterial ways in which a body can desperately try to make itself seen, heard, felt, in a world that doesn’t give a shit about seeing you, hearing you, feeling you?

From “The Politics of Disquiet: Diamanda Galás in conversation with Edward Batchelderâ€:

Galas: In the state of disgrace and invisibility are they supposed to go to old folks homes where they can comfortably lose their minds? Are they supposed to drink themselves to death? What are they supposed to do as people who are just human receptacles of nothing, and who are not heard? I don’t know. There is an expression that my friend Michael Flanagan and a friend of his, John St. James, used when addressing the AIDS epidemic: death by media. Which is that most of the media was responsible for actually killing people with AIDS, making them commit suicide, giving them a sense of despair. And with hepatitis , I must say, because the articles you read in the newspapers are just so not where the state of medical practice is now, it’s very discouraging. This kind of reception in the media that tells people to shut up and that their pain is of no importance to anyone is the kind of thing that can drive a person completely crazy. That means a number of things, but with no will to live, you know, there are very few options.

From Laurie Penny’s â€Panic on the Streets of London:

Months of conjecture will follow these riots. Already, the internet is teeming with racist vitriol and wild speculation. The truth is that very few people know why this is happening. They don’t know, because they were not watching these communities. Nobody has been watching Tottenham since the television cameras drifted away after the Broadwater Farm riots of 1985.

Most of the people who will be writing, speaking and pontificating about the disorder this weekend have absolutely no idea what it is like to grow up in a community where there are no jobs, no space to live or move, and the police are on the streets stopping-and-searching you as you come home from school. The people who do will be waking up this week in the sure and certain knowledge that after decades of being ignored and marginalised and harassed by the police, after months of not seeing any conceivable hope of a better future confiscated, they are finally on the news.

In one NBC report, a young man in Tottenham was asked if rioting really achieved anything:

“Yes,” said the young man. “You wouldn’t be talking to me now if we didn’t riot, would you?

Two months ago we marched to Scotland Yard, more than 2,000 of us, all blacks, and it was peaceful and calm and you know what? Not a word in the press. Last night, a bit of rioting and looting and look around you.”

Eavesdropping from among the onlookers, I looked around. A dozen TV crews and newspaper reporters interviewing the young men everywhere.

Vandana Shiva, From Seeds of Suicide to Seeds of Hope: Why Are Indian Farmers Committing Suicide and How Can We Stop This Tragedy?

200,000 farmers have ended their lives since 1997.

Farmers’ suicides are the most tragic and dramatic symptom of the crisis of survival faced by Indian peasants.

Rapid increase in indebtedness is at the root of farmers’ taking their lives. Debt is a reflection of a negative economy. Two factors have transformed agriculture from a positive economy into a negative economy for peasants: the rising of costs of production and the falling prices of farm commodities. Both these factors are rooted in the policies of trade liberalization and corporate globalization.

In 1998, the World Bank’s structural adjustment policies forced India to open up its seed sector to global corporations like Cargill, Monsanto and Syngenta. The global corporations changed the input economy overnight. Farm saved seeds were replaced by corporate seeds, which need fertilizers and pesticides and cannot be saved.

Corporations prevent seed savings through patents and by engineering seeds with non-renewable traits. As a result, poor peasants have to buy new seeds for every planting season and what was traditionally a free resource, available by putting aside a small portion of the crop, becomes a commodity. This new expense increases poverty and leads to indebtness.

The shift from saved seed to corporate monopoly of the seed supply also represents a shift from biodiversity to monoculture in agriculture. The district of Warangal in Andhra Pradesh used to grow diverse legumes, millets, and oilseeds. Now the imposition of cotton monocultures has led to the loss of the wealth of farmer’s breeding and nature’s evolution…

The suicide economy of industrialized, globalised agriculture is suicidal at 3 levels – it is suicidal for farmers, it is suicidal for the poor who are derived food, and it is suicidal at the level of the human species as we destroy the natural capital of seed, biodiversity, soil and water on which our biological survival depends.

*

I’ve often felt that we needed a furious queering of health. More than that: an intersectionality (Crenshaw) of health. Of skin conditions and the non-normative.

The skin off my back, skinned alive, she has a thin skin, you have to have a thick skin, show some skin. The skin being a hide, a hiding, it’s so hot out, why are you still wearing long sleeves, why do you wear black tights, why are you wearing a hoodie, what are you hiding, do you have something to hide?

Once I nearly burst into tears at a TK Maxx looking for a suitcase to buy, because every piece of luggage was being advertised as super light! and super hard/durable!. Lightness and hardness. What I wrote to my friend Masha about it:

Recently I had to look at suitcases, and the two desirable qualities that were being emphasized over and over again were: lightness and hardness. Either it’s super light and you can carry it anywhere and it never weighs on you or pulls you down; or it’s super hard and indestructible and nothing will ever damage it or destroy it or even make a scratch on it. You won’t know it’s there and you’ll never be injured.

And that’s the nightmare of the world we live in. Weightlessness and defense. Light and hard. Light and hard. It’s even worse than liquid modernity. Everything is a carbon fiber shield. We’re all turning into carbon fiber shields. I almost started crying in the fucking store. Was shaking and shaking.

The hard or healthy shell; it doesn’t have to hold together, it is together, or that’s the illusion it tries to pull off. You never feel it holding itself together unless it’s already fraying at the seams. No way to avoid feeling your own worldliness, your own in-the-world-ness and being-a-world-ness, when something’s “wrong†with your skin. Like: my brother’s deep shame and awkwardness about his acne, and now his acne scars, which I love, and which our older brother has, too. Losing the perfectibility of the skin means losing the illusion of perfectibility, full stop.

I always wonder how it would be possible to do away with the hermetic, the hermetic seal order of everything–or, not do away with the hermetic entirely, but to do away with the part that the hermetic turned into, which is to say, the scientific without its magical root. The magic of: still believing that flesh was ensouled, historical, political. That the world mattered to matter, and matter mattered in the world. That what happened to the bare and fragile body was a worlding in and of itself. That what happened to the body was also a meaning of the world.

The fragile body: the body that cannot help but feel its skin, because the condition of the skin differs from the dominant normative representations of skin as: smooth and hydrated (all the 3D mockups in beauty advertisements showing skin looking like cracked deserts, wastelands), impermeable/non-porous (all those beauty tools and creams to help “minimize your pores,” the desire to be ever smaller, ever tighter, ever more closed, homogenized), not “discolored” but uniform in tone and pigmentation, the standard of which being, of course, the-lighter-the-better (the beauty product description of “normal to dark skin”, dark skin being apparently abnormal; not to mention the use of skin lightening creams, which many of my friends growing up used, much to my dismay). Who isn’t smooth, who doesn’t have access to high-quality water, who has big pores, who has multiply pigmented skin, who is dark? When doctors and relatives talked pityingly about me as a fragile child, I always wanted to protest, But I can’t help it. I want to say it again, also as a protest, I can’t help it. I can’t help but feel it.

*

Now, this may be a Filipino-American urban legend I heard from my cousins, but someone told me once that some Filipinos were able to avoid compulsory military service because having eczema does something to your inner ear function; to your sense of balance, or to your sight. That under duress, you see get dizzy more easily, you see double. You’re unreliable as a marksman. They can’t trust you to shoot the enemy. Given that so many Filipinos have been historically involved or implicated in the U.S. army and its satellites within the military-industrial complex–like my grandfather who worked on an army base in Guam, my older brother who works as a security guard for NASA, and my younger brother if he eventually becomes an army nurse, if I don’t succeed in persuading him otherwise–I wonder, is this eczematic compromising of eyesight and marksmanship one of the ways a body might revolt against its own co-option; a condition that cleverly prevents you from fighting on behalf of the corporate-imperial power whose micro- and macro-aggressions and impingements upon your person, your life, are likely the cause of the symptoms in the first place? How does your body perform what might be called sub-conscientious objecting? Unreliable as a marksman, untrustworthy colonial subject. See double: bifurcated vision, bifurcated allegiances. Can’t shoot the enemy because can’t be sure who the enemy really is, when you’re a colonized person fighting on behalf of a colonizing power.

“A short stay in hell,” Jarman says. But bodily hell is also social hell and vice versa (vicis, versus, change it, turn it around, revolutions and turning). And not all stays there are short.

*

Speaking of eczema and people of color: since 2010 I’ve loved Mesut Özil’s face, have talked about him a little bit here and there. I know, I know, intégration par le sport is a hugely problematic if not entirely failed and outdated notion (though I retain some affection for things, particularly political things, that are failed and outdated; thinking through their failure and timeliness and untimeliness), RESPECT is a joke, and the racism faced by athletes of color particularly during this present Euro Cup is staggering. Just recently Özil was the target of racist tweets after the Germany-Denmark game, in which he, as a third-generation Turkish-German, was accused of not being fit to play for the German team. Italy’s Gazzetta dello Sport recently published a cartoon of their striker Mario Balotelli depicted as King Kong. Also, let’s talk about the disturbing martial metaphors commentators use in all popular sports, and the gradual change in tactics in the game itself to become more martial, offensive-defensive, rather than the multiplicity of flows that people say the game used to be, and some people say women’s soccer still is (though of course massively less watched, even by the one who writes this post, gah).

But of course I was nevertheless happy, really stupidly happy, in 2010, when Özil became the most-well known face of the German national team, the new Zidane (another love), another midfielder who sees the game like a psychic, a beautiful and resourceful mover, a débrouillard, someone who opens up space, who creates and is sensitive to gaps, like Ayrton Senna. Loved all the close-ups on Özil’s fierce, serious, thinking face on the pitch. Thinking about all the excitement in 2010 around Özil and Boateng and Khedira and Klose and the fresh, young, multiethnic German team. I fell for it hook, line and sinker, what can I say. Not to mention the fact that Die Mannschaft’s players’ politics are faintly more progressive–for the homosocial masculinity theatre that is international football, at least–than other big national teams; multiple players on the German team, thinking particularly of Lahm, Neuer, and most passionately Gómez, have all condemned homophobia in football; though Lahm (who nevertheless was given the Tolerantia prize?) as captain is decidedly more pessimistic about the possibilities of gay footballers coming out, Gómez, from what I’ve read, is more optimistic and outspoken and outright condemning.

But in Özil, what I love most are his eyes. A lot of people come to my blog, it seems, looking for information about Özil’s eyes. Recent search: “mesut ozil why he has black circles under eyes.” But the circles around his eyes aren’t always black, dear Searcher. They’re most often red, or purple-red. Which I think (I can’t know for sure, and Google-stalking hasn’t revealed any answers) indicates that he has some form of eczema, as it’s so similar to how my facial eczema used to manifest itself. The hot red halo around the eyes, reaching even to the temples. Every time I see him, I’m moved in the part of me that remembers pain. When it was really bad for me, I used to philosophize about what these rings around the eyes could mean, so hot, rough and itchy (they were so itchy, they vibrated with itching; you know those alien worms in Holloway’s eyes in Prometheus? itchy like you imagine that would be itchy; I always thought that there must be parasites in my eyes, and who knows, maybe there were).

In my case, the eyes were always particularly inflamed during moments of stress. I always got them when I traveled, when I was seeing a long-distance lover again after too much time apart (any time was too much time with this long-distance-lover-turned-husband), if I was around my mother, if I was around my in-laws. If I was writing poorly or writing well or not writing at all. If someone I loved was hurt, or dying, or freshly dead, or dead for a long time but it doesn’t matter, you’ll never get over it, never, never, never, never–

Thinking about Özil’s eyes. About how Özil sees the game and plays it, his assists, his deft and elegant manuevering. How he gets himself out of shitty positions, impossible situations. How he places the ball perfectly, as if he knew you were going to be there, when you weren’t yet there. Isn’t a playmaker a kind of visionary? You have to be able to somehow see, feel, predict, the future. I wonder, were there mystic visionaries got eczema around the eyes? Teresa de Avila, Julian of Norwich, Hildegard von Bingen, anyone? People looking intensely and looking everywhere. Looking past looking. Overworked vision, inflamed. (Doesn’t that often happen in anime, as well; a villain doing something particularly evil, or a hero doing something particularly heroic, and all the veins bulge around his eyes to show the senses working overtime? I feel as though this was a formative image in my anime-watching and manga-reading childhood.)

Seers. People said of Zidane, people say of Özil: he sees the game. But the seeing here is extrasensory. Jarman: “Red adapts the eye for the dark. Infra-red.” Eczema-red adapts the eye (or is the bodily symptom of the adaptation) for the seeing beyond sight. Or even, beyond beyond: under, below, further (infra). Red goes deep. Or, as Masha Tupitsyn wrote in “The whole world is actually red and green”: “Red is feeling deeply—deeper—and losing something or someone deeply, too.”

Red not oceanic deep but: earth-deep and blood-deep. Burrow-deep and skin-deep–which is actually really very deep. You stop using skin-deep as a pejorative term for superficial when you realize the multidirectional vastness and profundity of the skin. When people use depth metaphors like “bowels of the earth”, I wonder if they remember also that the body also is like a tube, that the internal skin of the colon is continuous with the outer and visible skin, that the bowels of the earth are also its innermost skin, its skinmost skin, our bottoms being bottomless, and so, skin, skin is deep, skin, skin goes in.

At the last match, Germany vs. Greece (what everyone was comparing to the Battle of the Eurozone), Özil was named Man of the Match by Fifa. German audiences however, apparently considered him the least effective player, and it’s true that in my experience, all of the German people I know have some visceral distaste for Özil. I say visceral, I mean: “racist.” Once, when I was telling a German person in Munich how much I loved Özil and his style of play, and that I found him beautiful, the person said to me, “Really? But he has such a big nose.” Indicating an enormous nose on his own face.

I was shocked. Still, Germany, really? “I love his nose,” I retorted. Thinking about how German courts recently ruled that circumcision shall be judged and punished as a bodily harm, rightly condemned as blatant racism by Jewish and Muslim communities, as well as women’s rights groups. France and the veil. America and the hoodie. Germany and the foreskin. Someone, someday, must write an essay about the racist paranoia around the dark, hidden and unseen; its valorizing of exposure, illumination, “enlightenment.â€

The word that kept recurring in the comments of this Guardian article about the law was: barbaric.

Barbaros, that most ancient of xenophobic slurs. What Greeks, particularly Attic Greeks, called their Persian enemies: anyone who, instead of speaking good, imperial, Attic Greek, spoke like this: bar bar bar bar (why I wrote this poem once). They weren’t above calling certain Greeks to far to the east near-barbarians, either; it was whispered that Sappho’s Aeolic dialect was practically a barbarian speech, so close to Asia Minor was Lesbos. What Romans called Germans and the people surrounding their growing empire. Barbarian. The xenophobic word for: those lesser people who say shit and do shit that we don’t understand because we’re too fucking stupid and inured on our own smug imperial arrogance to try to understand it, and anyway, it isn’t worth understanding. The barbarian is always that which is Other, and the deployment of the word is crucial in the practice of dehumanizing and demonizing that other (the way David Cameron named the rioters as a “feral underclass”), the better to push forward the kind of savagely (!) unequal measures necessary for the total disenfranchisement and eventual annihilation of that other. From Cameron’s recent speech on the welfare state: “In a world of fierce competitiveness – a world where no-one is owed a living – we need to have a welfare system that the country can properly afford.†A world where no one is owed a living—of course, no one is owed a living, because aristocratic and corporate elites like David Cameron take it as given for themselves and only themselves. “No one is owed a living (but us).”

For could it not be called barbaric what the neoliberalist agenda of Germany, the IMF, the European Central Bank and corrupt ruling elites have perpetuated within the Eurozone, in particular countries like Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal, all while citizens of such Southern countries are called “lazy” and not yet properly “evolved” for a “modern” economy? A week ago, I overheard on the street: “Greece, they’re not even a proper country. Lovely vacations and olive oil, that’s it. It’s not right, innit, us paying for them to retire early and lounge on the beach?”

A typical fallacy, the Süddeutsche Zeitung reminds us: “Not one euro has yet flowed from Germany into the Greek pension system.”

[Germans] denounce their “irresponsible†eurozone neighbours, but they know that Germany’s economic boom depended on higher spending in the rest of the eurozone.

Germany has one of the world’s biggest export economies. Some 60 percent of its exports go to other eurozone countries.

The introduction of the euro in 1999 gave Germany a massive boost.

While German banks sent money to peripheral eurozone countries, those same countries imported German goods.

The boom in Germany was only made possible by the German government’s “Agenda 2010†attacks on workers’ wages, rights and conditions.

Greek and German bosses did well out of their relationship—at the expense of Greek and German workers. But now the bubble has burst, the bosses are turning on each other.

But no, it couldn’t count as barbaric. Barbaric is a word used by power. The powerful will impose austerity measures that will ensure debt slavery, deepen unemployment, accelerate the selling-off and privatization of assets and social services, and the continued siphoning of national wealth into the bank accounts of wealth corporate and government elites—but my god, in their brutality, they shall be civilized!

Richard Seymour at Lenin’s Tomb:

The Eurozone leaders reacted to the deal, to this complete capitulation signed on behalf of Greece by its unelected government, by dismissing the agreement and demanding more. The actual amount of additional cuts they demanded is fairly piddling compared to the agreed total and, you would think, hardly worth scuppering an agreement for. But the contempt conveyed by this gesture is jaw-dropping. It goes without saying that they don’t care if a fifth of Greek workers, and just under half of young Greek workers, are unemployed. Knowing that the government is widely seen as a slave of external powers, European bankers, EU leaders, the ECB, and the IMF, they demanded further prostration from the Greek government and ruling class. Knowing that the struggle against cuts in Greece is now suffused in the popular imagination with the national resistance to Mussolini’s invading forces beginning in 1940, they opted to underline the sense of national humiliation. Knowing that the left-of-PASOK parties could win any election called in the near future, they demanded the bourgeois parties add petrol to their own immolation. Knowing that there is a volatile, violent mood, that the tempo of working class struggle is escalating, that strikes will continue over the weekend when the package is put to a vote, that more defections are on their way, and that the government may not survive for long, they smacked it down for following orders. Knowing, aside from anything else, that the police federation is angrily claiming that it is not willing to keep a lid on popular anger, and that the head of the civil servants union is predicting a “social uprising”, they’ve raised their two fingers and said ‘bring it on’.

“If you choose to live in Europe, you adapt to OUR lives and society. You are welcome to maintain practices and culture providing it does NOT flout EU law!†wrote the Guardian commentor. Indeed. You are welcome to remain in Europe as long as you submit to just that very notion: that what the EU says is law, and the EU’s elites make the law for themselves. The old bitter pun, truth: Justice really means Just-us.

*

Before the game against Greece, Özil had been playing well but not obviously spectacularly, and so when interviewers asked coach Joachim Löw why he had not yet performed to the best of his ability:

Löw took sharp exception. “Maybe the coach sees what you do not see,†he said.

“The problem is not Özil, it is that his team-mates need to make more varied runs to give him more passing options.†This may explain why despite three wins in the group phase Löw still felt compelled to make three changes in the quarter-final, with those areas most dependant on Özil’s creative eye refreshed.

Who sees what you do not see? What does the creative eye see? When people (typically male sportscasters) talk about someone seeing, the way people talk about Özil seeing, I think they really mean: I can’t see what he sees. I don’t even know what he’s seeing. I had to watch the replay. I don’t know how he sees what he sees. What he sees is different from what we see. More like: what he sees is not something you see.

Recently, however, when fans talk about Özil, I notice they often mention that he looks: depressed, out of place, exhausted, lost his magic (although admittedly, this has stopped recently, as his performance for the German national team has been increasingly astonishing, the passes and assists he’s been making, the general consensus being he’s come back into his own magic, the magic that drew attention to him in 2010). Another recent semi-regular search leading to my Tumblr: “mesut özil sad.” After Germany’s dynamic debut at the World Cup in 2010, Özil was purchased from Werder Bremen by Real Madrid for around fifteen million euros. Sami Khedira, another German player with an immigrant background, accompanied him to Madrid, too, moving from Vfb Stuttgart.

“Life is hard for the newcomers,” it was reported. Real Madrid coach José Mourinho said:

Life for the two Germans is not an easy life. They don’t speak a single word of Spanish. They only say ‘buenos dÃas’ and ‘hola’. They don’t go further.

The work we do in field is intense and luckily I have an assistant who speaks some German and gives them my instructions. But it’s not easy for them to get my message as I wanted.

Besides, social life with the group is still zero for them. Khedira lives with Özil and Özil lives with Khedira. Their entry into the group is not easy yet, even though the group is young, friendly and easy to deal with. They don’t even speak English well. They speak it a little better than Spanish, but it’s so hard that way. Patience, we have to give them time.

Sara Ahmed, “Multiculturalism and the Promise of Happiness”:

We can see here that the shift from unhappy to happy diversity involves the demand for interaction. The image of happy diversity is projected into the future: when we have ‘cracked the problem’ through interaction, we will be happy with diversity. That football becomes a technique for generating happy diversity is no accident: after all, football is proximate to the ego ideal of the nation, as being a level playing field, where aspiration and talent is enough to get you there, providing the basis for a common ground. Diversity becomes happy when it involves loyalty to what has already been given as a national ideal. Or we could say that happiness is promised as a return for loyalty to the nation, where loyalty is expressed as ‘giving’ diversity to the nation through playing its game…

And indeed, a news item on June 24: “Mesut Özil in battle to win German hearts.”

However, nearly a year ago, at the Real Madrid match vs. FC Barcelona, El Clásico, a brawl between the players broke out following Madrid leftback Marcelo’s strong foul on Barcelona’s Cesc Fà bregas.

Before I go further, talking about these teams, an important reminder, in the words of From a Left Wing:

Meanwhile corporate speculation has sucked the soul from the men’s game. Who believes that the season championship is something that a team earns? What honor is there in a trophy that’s been bought? Or in watching a play-off between two or three teams that have sold their economic souls in order to have the right to be in the running?

And Voyou Desoeuvré, “A Victory for Spain is a Victory for Neoliberalism”:

While in terms of the nations the teams represent Germany vs. Greece was often talked about as a clash of neoliberals against their victims, from a purely football point of view it seems clear to me that the Spanish team are the standard-bearers for neoliberalism. Spain have perfected the style of play that is most in tune with the ongoing neoliberalization of football. The passing style of play is made increasingly attractive by the rules changes which discourage aggression in tackling (as can be seen by the results when the Netherlands tried to play a more physical style of football in the World Cup final in 2010), and these rule changes reflect the increasing amount of money involved in football: even a brief loss of playing time due to injury represents a considerable financial cost to a club. Of course it’s also true that Spain’s success with this style of play is a result of the exceptional talent of their players; it’s interesting that in recent years descriptions of Spain’s football have tended towards terms like “businesslike,†rather than the rapturous descriptions of the beauty of their play that was common a few years ago, but the most important point is that these two things are not incompatible. In flexibly-specialized postfordist capitalism, to be businesslike is to be virtuosic, making the sensible and sober business investment one in “human capitalâ€; it’s not a coincidence that Spain draws most of its players from Real Madrid and Barcelona, which are the two highest-revenue football clubs in the world.

The difficulty is that there’s no national team you can point to as an alternative to Spain’s neoliberalism; TINA, all the other teams are attempting to play the same neoliberal game as Spain, but are simply doing it less well.

What got me interested in this particular El Clásico brawl last year was the participation of the normally preternaturally calm (or so reputation maintains) Özil; his anger aimed at Barcelona striker David Villa. Later, Özil revealed that Villa had made some kind of Islamophobic comment: “I was defending my religion because David Villa insulted Islam.”

The commentary on this video is particularly revelatory. “For all of the good that Mourinho is putting into them, there’s this nasty edge. And it’s on FÀbregas. And it’s nasty as a rat bite from the back, from Marcelo. It’s wicked, it’s malicious, it’s verging on criminal…”

As he speaks, at 0:34, we can see Özil in the upper left reacting to Villa–it’s difficult to see in the video, but some speculate that there was a slap, along with his Islamophobic comments. His teammate pulls Özil back quickly, but it’s too late, he’s going in. The commentator cries, “And it’s all gone off!”

Continuing: “Even their fans don’t like to see this! It’s all right to be aggressive, all right to have that edge, to try to knock the Barcelona team off, and I welcome an aggressive approach to anything in football, but when it’s reduced to this, it gives the game a bad name, and it gives El Clásico a bad name. And we’ve seen it, the last four Classics, that this has come out and spilled over the top…”

As the commentator speaks-shouts, we see Özil (1:10) shouting, struggling, protesting. Adriano on that Barcelona team is holding him back, along with another football official. He won’t be held back, keeps going towards Villa. Another official has to step forward, then Pepe, then Carvalho. Everyone is struggling to hold onto him, restrain him. At 1:40, flanked by teammates and officials, he is still protesting, moving forward. Even Marcelo, the one responsible for the foul in the first place, diverts his energy now to holding Özil back.

The second, American, commentator, trying to get a word in edgewise: “Özil appeared to have been slapped!”

The first commentator, still talking over him: “[They’re] bigger than this, Phil, Real Madrid. They are a wonderful, great institution…”

The fight reminded me of what happened during the World Cup Final in 2006: Zinedine Zidane’s infamous headbutting of Marco Materazzi, which I have been haunted by since watching it. Haunted by the way the rhetoric that followed, the swift turn against Zidane, the prioritizing of impersonal professionalism above all, the imperative to maintain the game’s good reputation, the singular importance of fair play (this, in a game that had already been characterized by several dirty fouls and tackles). That Materazzi had insulted Zidane’s mother and sister–all right, this was lamentable, certainly, but still, apparently, would not “excuse” or “absolve” Zidane’s actions. Zidane should have been above it. As Özil should have been above it.

“It” being always things like: xenophobia, racism, homophobia, sexism, personal attacks in a professional environment. The things you’re supposed to get over, the things you’re supposed to already be over, if you’re a mature, well-adjusted adult professional. But as Jiddu Krishnamurti says, “It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a sick society.”

“Football is proximate to the ego ideal of a nation,” Ahmed writes, and it is a deeply normative ego ideal, what with its homosocial codes of masculinity, its insistence on an ideal of sportsmanlike comportment that nevertheless fails to truly address and combat the all-pervasive and structural racism and homophobia in sports culture, its emphasis on the professional, on the protection of the sport-as-institution above all (“They’re bigger than this, Phil; Real Madrid is a wonderful, great institution”), its vision of diversity as an illusion of seamless integration producing a kind of ninety-plus-minute realm transcending politics, a realm even transcending the personal, into the mythic, to ultimately produce: The Beautiful Game. For the personal and political to erupt into that sphere, would be to contaminate it–and such contamination is unacceptable.

“It tarnishes the reputation,” the sportscaster says, while Özil reacts to Villa. Journalists and commentors spoke similarly of Zidane: that he had sullied the game, sullied the reputation of the French team. Demanded that he apologize, to Materazzi (he refused), to the nation, to the fans (he acquiesced).

At the end of the World Cup final in 2006, when the French team lost, no one in the French audience I was watching the game with clapped for Zidane, even though my husband and I were shouting, “Merci, Zizou!” Shortly after the headbutt, there was a real sense that Zidane’s rage had betrayed France; that he had prioritized his “personal” feelings about a “personal” attack, over the good of the nation, the team, the game. Showed a lack of team spirit, was unprofessonal, was unsportsmanlike conduct.

But it’ll come as a surprise to no reader, I’m sure, that I value messy and uncontainable emotional and affective reactions that dissolve the boundaries between one’s “work” and one’s “life,” between being a professional and being a person, historicized, politicized. It remains moving to me that both Zidane and Özil in these incidents refused to bracket off their personal lives or politics, their emotions and their attachments and convictions, valid at any time and any place. That they had complex attachments they refused to relinquish “at the door,” as people often say, when they’re speaking of entering into and becoming part of some Institution, be it academia, the workplace, or similar. Whatever your own personal issues and politics, leave your shit at the door. Well, what if you don’t or can’t leave your shit at the door? What if you carry all your shit with you, all the time? What if you refuse to separate your shit out? What if you have the audacity to try integrity as a way of life–that is to say, try to be integrated? The radical refusal to leave your anti-racism, your anti-xenophobia, your anti-sexism, your anti-Islamphobia, at the door.

Why couldn’t Zidane just ignore it? Why couldn’t Özil just let it go? Why couldn’t they just play the game, take one for the team? Why did they have to remind us of their difference–that their priorities may in fact be differential, and different?

Ahmed:

The figure of the melancholic migrant is a familiar one in contemporary British race politics. The melancholic migrant holds onto the unhappy objects of differences, such as the turban, or at least the memory of being teased about the turban, which ties it to a history of racism. Such differences–one could also think of the burqa–become sore points or blockage points, where the smooth passage of communication stops. The melancholic imgrant is the one who is not only stubbornly attached to difference, but who insists on speaking about racism, where such speech is hard as labouring over sore points. The duty of the migrant is to let go of the pain of racism by letting go of racism as a way of understanding that pain.

It is important to note that the melancholic migrant’s fixation with injury is read not only as an obstacle to their own happiness, but also to the happiness of the generation-to-come, and even to national happiness. This figure may even quickly convert in the national imaginary to the ‘could-be-terrorist.’ His anger, pain, misery (all understood as forms of bad faith insofar as they won’t let go of something that is presumed to be already gone) becomes ‘our terror.’

To avoid such a terrifying end point, the duty of the migrant is to attach to a different, happier object, one that can bring good fortune, such as the national game…

In July 2006, France lost the World Cup. In August 2011, Real Madrid lost Él Clasico. In both of these games, Zidane and Özil received red cards for their actions.

*

“To say red, to show red, is already to open up vistas of disagreement.”

*

Something else I think Jarman leaves out, when he talks about red in his essay, is feminine red. When he says that red is explosive, that red is rare, a moment in time, quickly spent intensity (“Red is a moment in time. Blue constant. Red is quickly spent. An explosion of intensity. It burns itself. Disappears like fiery sparks into the gathering shadow. To warm ourselves in the long dark winter when the red has departed. We welcome the robin redbreast, and the red berries that sustain life. Dress in the Coca Cola red of Father Christmas, the bringer of gift…”)–he perhaps forgets or overlooks that for menstruating women, red (like green) returns. Red remains, endures, trickles away, trickles back in. Ebbs and flows. Has a weight; a gravity. A pull. Doesn’t only explode or aggress; has a varying velocity, sits for a long time in the body and on what parts of the world it meets: its stains remain. What about the deep and cyclical constancy of red, reddening? The red time you live in; move towards, move away from. I’m always either moving towards or moving away from red. I’m always waxing and waning.

Jarman: “Red is rare in the landscape. It gains its strength through its absence. Momentarily, in an ecstatic sunset, the great globe of the sun sinking below the horizon … then it’s gone. I’ve never seen the legendary green flash. Remember, great sunsets are the consequences of violence and cataclysm, Krakatoa and Popocatepetl.â€

So Jarman says, but it isn’t quite true: red is everywhere in the landscape, is its lifeblood. Or maybe it’s time to stop looking at the world in terms of landscape–what other worldings can there be, besides the geographical or cartographical? (Reasons I can’t be a real Deleuzian: my dislike and distrust of the map.) Corporeography. Corporeal-scapes. Red blood, red soil. Iron and iron ore. (Iron Man is red and gold.) Red isn’t so rare in the anything-everything-scape; what about the red you came from? Blood isn’t only for the horror film, the slasher: blood not only as spurting, gushing, gore. I want to think about and feel through lifeblood, a word I use a lot. Lifeblood, not only deathblood, killblood. Once I wrote to Masha about the mystical properties of blood, which my mother believes in and which I believe in, despite no longer believing in my mother. The ritual she made me undergo at the age of eleven, which I think I’ve mentioned here before somewhere, or it was possibly in a poem in CANDIDA, the horrified gossip of my classmates after I made the mistake of telling one friend about the ritual, which consisted of: washing my face with my very first period-stained underwear, to ensure smooth skin (folk magic; did other Filipinas do this? please write to me!).

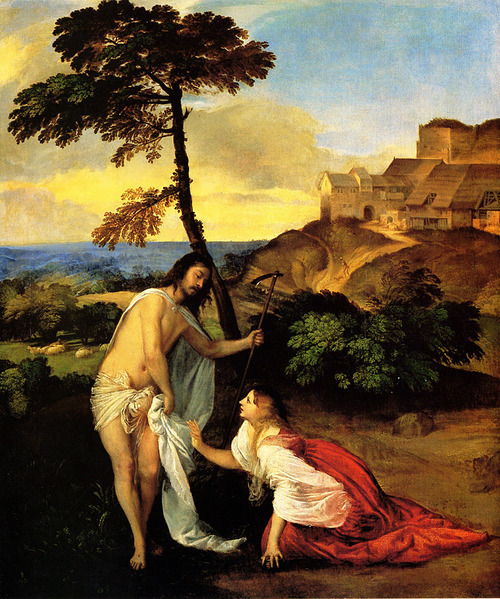

Back then I also sent Masha the story in the Gospel of Matthew, about the woman who goes to Jesus to be cured of her excessive bleeding, and wishes only to touch the fringe of Jesus’ cloak; her faith being such that she knows contact with his garment alone will save. Then he unfolds the concentrated kernel of her faith, when he says, Daughter, your faith has made thee whole.

Touch that heals, faith that makes whole. A cloth soaked in your own blood that preserves you. Red of viscera, of the visceral. Red of the inner of life (innard life).

And what about red and impurity? The menstruating woman banished out of the community for the time of her monthly contagion. Terror of menstrual blood, childbirth blood and afterbirth blood, bad blood, sick blood, blood on your hands (Macbeth’s hysteria over blood–will Neptune’s ocean wash me of this deed, etc–Lady Macbeth washes it off with water). Several natural healers and acupuncturists told me I had eczema and the other illnesses because I had bad blood. Dirty blood (which for a fee and regular sessions, they could clean, of course; especially one male acupuncturist and natural health practitioner, who became obsessed with healing me and whom I once had to firmly castigate before his–all female–employees, before leaving the clinic). Impure woman’s blood.

Minh-ha:

Many of us working at bringing about change in our lives and in others’ in contexts of oppression have looked upon red as a passionate sign of life and have relied on its decisive healing attributes. But as history goes, every time the sign of life is brandished, the sign of death also appears, the latter at times more compelling than the former. This does not mean that red can no longer stand for life, but that everywhere red is affirmed, it impurifies itself, it necessarily renounces its idealized unitary character, and the war of meanings never ceases between reds and non-reds and among reds themselves. The reading of ‘bad blood’ and ‘good blood’ continues to engender savage controversies, for what is at stake in every battle of ideologies are territories and possessions.

For who is pure and impure? Who has the power of the prophylactic, and who submits her miasma for scrutiny, containment, eventual sanitation? Noli me tangere, Jesus said to Mary Magdalene, clinging to his robes. “Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father: but go to my brethren, and say unto them, I ascend unto my Father, and your Father; and to my God, and your God.” But then later he let Doubting Thomas directly touch his wound. The brothers can touch you, but not the whore who loves you. I’m not a biblical scholar, there’s probably more to this. But this already is enough for me.

The red woman is untouchable.

Did she just catch him at the wrong time, too early (“not yet ascended to the Father,” which has its own issues), when he couldn’t have been touched by anyone? Women and the untimely. Women and the unclean. Women and their red clothes, women and their menstrual blood, women and their bleeding hearts. The sentimental is bloody: it’s what you feel. What’s telling is that the way it’s an insult to tell a person (a woman): “You feel.” Feeling, in certain (gendered, sexualized and racialized) bodies, is always too much.

Mary Magdalene was that word that people use to deride the scandal of desiring women: “clingy.” Don’t touch me, don’t cling to me. What clings, remains, stains? Hollywood movie trope: the bitch who won’t die, the girl who won’t get a clue, he’s just not that into you. Who or won’t let go. Like Sara Ahmed says in “Feminist Killjoys,” minoritized people everywhere being told to get over it–whatever their grievance is–to just let it go already. Why do we fear and vilify that which (she whom) doesn’t let go, that doesn’t get over it, that holds on, that remembers, that leaves a stain, that sticks, that’s sticky, that contaminates?

Women and the stain of love. Sticky, sentimental, won’t-get-over-it, love. From Juli Carson’s “Exile of the Imaginary: Politics / Aesthetics / Love”:

Love is an “atopic” discourse. It induces an allergic reaction in the conventional critic to something completely out of place. In critical analysis, love is something that must be cleaned up, a sort of stain that both hides and reveals what is lacking in scientific discourse: the analyst’s desire. To reveal the analyst’s desire–the fact of his Imaginary attachment to his object of study, which is to say, the libidnal locus of his ideal-ego–is to sully the site of analysis, forbidden as such desire is. A stain or spot of this sort can thus be an eyewitness of a crime, as it was for Lady Macbeth, who pleaded “out out damned spot” when she tried to erase a spot of blood that refused to go away. But as we know in the case of Macbeth, the more one attempts to clean a stain, the dirtier the scene gets. In the world of criticism, love-as-stain is a self-perpetuating exile machine, if not of the critic himself then of an entire discourse…

Bruce Fink rhetorically asks: in the name of what does one get thrown out of their field? He answers that it is always in the name of science. ‘Whenever you want to throw someone out of your field,’ Fink argues, ‘you claim that his or her work is unscientific, i.e., that it cannot withstand serious theoretical scrutiny or is scientifically irresponsible. In other words you appeal to Science with a capital S…

I love the idea of love inducing an allergic reaction in the conventional! Love, contaminating Science, contaminating Power, contaminating the idea of Objective Critique. Love-as-stain being a self-perpetuating exile machine echoes what Jarman wrote about eczema: your sensitivity (skin, heart) is always setting you apart. You have to be quarantined. The risk of contamination is high.

Contamination: com and tangere, together and touch. Touching together, things that make things touch together. This is also why the corporate state breaks up occupations and is rapidly criminalizing the right to gather and protest: what they are fighting is precisely contamination: the together-touching (tactile-material, not only remote-controlled) of people being together, particularly being together in public. The energy–which is always a collective energy, a connective energy–of contamination.

Franco Berardi, “Info Labour and Precarisationâ€: “How can we oppose the decimation of the working class and its systemic de-personalisation, the slavery that is affirmed as a mode of command of precarious and de-personalised work? This is the question that is posed with insistence by whoever still has a sense of human dignity. Nevertheless the answer does not come out because the form of resistance and of struggle that were efficacious in the C20th appear to no longer have the capacity to spread and consolidate themselves, nor consequently can they stop the absolutism of capital. An experience that derives from worker’s struggle in the last years, is that the struggle of precarious workers does not make a cycle. Fractalised work can also punctually rebel, but this does not set into motion any wave of struggle. The reason is easy to understand. In order for struggles to form a cycle there must be a spatial proximity of the bodies of labour and an existential temporal continuity. Without this proximity and this continuity, we lack the conditions for the cellularised bodies to become community. No wave can be created, because the workers do not share their existence in time, and behaviours can only become a wave when there is a continuous proximity in time that info-labour no longer allows.”

What was the occupation of Tahrir Square but the most profound sharing of existence in time (remaining in the time of “not until he leavesâ€) and spatial proximity of bodies? Despite the attempts of social media corporations and their supporters to co-opt the protests, to position themselves between bodies and bodies. Reciprocal branding: the Twitter revolution, Twitter as revolutionary. I’m so materialist, with my suspicion and reticence. I still want to think of shared time and bodies in time.

*

But increasingly, we’re not supposed to want to share time, and share bodies in time. While checking my email recently, I watched a KLM Airlines advertisement for their Be My Guest campaign, part of their new feature, Meet & Seat. From their website:

Be My Guest

Are you a movie fan? Do you love fashion? Maybe have a passion for space? Just imagine sitting next to a world famous Dutch celebrity on a KLM flight. KLM is making it possible with Be My Guest!

Which Dutch icon would you like to travel with most:

Armin van Buuren – the best DJ in the world

Ruud Gullit – football legend

Yfke Sturm – supermodel

Dr. Ockels – astronaut

Jeroen Krabbe – Hollywood actor

Hella Jongerius – designerHow to participate

Go to Be My Guest, choose your favourite celebrity and have a virtual conversation!

Answer your celebrity’s 5 questions about your common interest – such as design, music or football. Who knows you might just be their ideal travel companion!

6 winners will go on a journey with their idol: Jeroen Krabbe for example will take his travel companion on cinematic journey to Venice. And Yfke Sturm will bring her ideal travel companion with her on a fashion trip to New York.

Meet & Seat

If you want to find out who will be on board your KLM flight anyway, you can. If you have booked an intercontinental KLM flight to or from Amsterdam and if you are travelling alone, you can now see who else will be on board and where they will be sitting – from 90 days before departure.

All you need is a Facebook or LinkedIn account. First, log in to Manage my Booking. Go to the tab ‘Seating’ and then to ‘Meet & Seat’.

What is Meet & Seat

KLM’s Meet & Seat lets you find out about interesting people who will be on board your KLM flight such as other passengers attending the same event as you at your destination.

Simply share your Facebook or LinkedIn profile through Manage my Booking. Next, check other passengers’ profile details and where they’ll be sitting. Of course you can also choose your seat.

Meet & Seat is a new KLM service – the first of its kind.

Social Steak (what a name), a social media and tech news blog, writes of the new feature: “Passengers can also view other passengers profiles and arrange to sit next to that person. This is a great idea and has the potential to create new friends or business contacts. Why sit next to someone you have no interests with? It could make a boring flight much more entertaining.”

Not only is KLM working to solve what is evidently the supreme grievance of shared transportation–physical proximity with strangers–but now, assisted by the social prosthetics of Facebook and LinkedIn, you can monitor who will be sitting on your flight, look everybody up, check where they’re sitting, locate and avoid your personal undesirables, foreclose all possibility of aporetic experience.

But what was to me most revelatory of the true strategies and implications of this campaign, was the tiny, short advertisement I saw to the side of my inbox, the glimpse that introduced me to this campaign at all. I can’t find it again online (how easy it is to be offensive in the 21st century: the protection of ephemerality, no one is accountable, was I offended, what offended me, you can’t find proof, it never happened), but this is what I witnessed:

One airline seat which split into two seats, which then spin into vertical reels, as in a gambling slot machine, so as to indicate that the wheel of chance will now decide the occupiers of this seat. (They choose a gambling metaphor, and yet the entire premise of the campaign is precisely to preclude chance encounter.)

A young blonde white woman appears on one of the seats. Smiling, she then presses a button (the slot machine “lever”) to spin for her seat partner.

A man of color (whom Wikipedia tells me is Ruud Gullit, the Dutch Surinamese footballer who dedicated his Ballon d’Or in 1987 to Nelson Mandela) appears next to her and smiles.

The white woman wrinkles her nose in distaste and presses the button again to change seatmates once more, to try her luck again. Her next seatmate is an older white man. She seems pleased, remains with her choice.

But then the older white man presses the button himself; his next seatmate is a young white man. They smile at each other. Now they are both satisfied. Now they can have a pleasant journey.

This is the trajectory of free choice, which is to say, the trajectory of discrimination. A young white woman doesn’t want to sit next to a brown man. An older white man doesn’t want to sit next to the woman. The only nod to diversity, perhaps, is intergenerational: white men of any age are happiest and most comfortable sitting next to each other. Everyone else is an untouchable. Undesirable seatmate.

The universal sign for NO: a big red circle with a red slash through it. Like a cut. Like saying: “Cut.” Cut out. Cut them out. Cut it out.

(I was able to find the video version of the ad I saw; it begins at 1:20.)

*

Sara Ahmed:

To be unseated by the table of happiness might be to threaten not simply that table, but what gathers around it, what gathers on it. When you are unseated, you can even get in the way of those who are seated, those who want more than anything to keep their seats. To threaten the loss of the seat can be to kill the joy of the seated. How well we recognise the figure of the feminist killjoy! How she makes sense! Let’s take the figure of the feminist killjoy seriously. One feminist project could be to give the killjoy back her voice. Whilst hearing feminists as killjoys might be a form of dismissal, there is an agency that this dismissal rather ironically reveals. We can respond to the accusation with a “yes”…

…Even if you do not want to cause the unhappiness of those you love, a queer life can mean living with that unhappiness. To be willing to cause unhappiness can also be how we immerse ourselves in collective struggle, as we work with and through others who share our points of alienation. Those who are unseated by the tables of happiness can find each other.

*

In her poem “After Watching Klimov’s Agoniya,†Fanny Howe wrote: “Love is the green in green. Does this explain its pain?”

Then I would say: life is the red in red. Does this explain its pain?

*

When I went to Berlin recently, the first day my thighs broke out in hives because I tried to wear pants for the first time in a while (have not been able to wear pants in years, skin on legs too sensitive), for two weeks legs were raw and itchy and feverish with blood. F. and I hovered our hands over my thighs; we could feel the blood radiating from within. Heat, but not only heat, not only the metabolic exertion of the immune system at work. But: the blood-aura. Somehow I could be embedded within it, but and yet at the furthest edge of its halo. It seemed to me then, seems to me now, that blood is musical (symphonic?). Plays the organs. Its deep, beep beat. So deep as to seem like a secret, when in fact it couldn’t be more explicit (hidden in plain sight). The end of medieval manuscripts: “explicitus est liber,” the book is unrolled. Explicitus est cruor? The blood is unrolled. Rolling and unrolling. What’s red in me I feel beyond feeling, hear beyond hearing.

Speaking of how red is felt in the body, the music of blood, and what can be felt extrasensorily, I love this, also, from it’s her factory’s article, “How To Subvert Biopolitical Administration/Big Data/Neoliberal Superpanopticism?”:

More interestingly, hip hop (and now dubstep and other hip hop inspired dance music) producers will often push the bass “into the redâ€â€”i.e., it’s too low for humans to actually hear, but it can be felt (standing in front of speakers in the club, listening in the car, etc.). By taking the bass signal into the red, there is a qualitative shift in the signal. As Tricia Rose explains:

Using the machines in ways that have not been intended, by pushing on established boundaries of music engineering, rap producers have developed an art out of recording with the sound meters well into the distortion zone. When necessary, they deliberately work in the red. If recording in the red will produce the heavy dark growling sound desired, rap producers record in the red. If a sampler must be detuned in order to produce a sought-after low-frequency hum, then the sampler is detuned…Volume, density, and quality of low-sound frequencies are critical features in rap production†(Rose, Black Noise, 75).

These producers are playing with “volume, density, and qualityâ€. This strategy makes sense, especially if, as both Puar, Jeffery Nealon, and others argue, neoliberalism manifests in/as the organization of intensities.

So, it seems to me that this idea of modulating something “into the redâ€â€”modifying the intensity of a signal so that it effects a qualitative shift—is a good way to start thinking about how to subvert neoliberal biopolitical administration. This form of power manifests as the regularization and regulation of frequencies, the stabilization of a signal. You modify signal with signal (e.g., an electric signal made by turning the potentiometer on a volume knob makes the mp3 play back louder or softer). Subverting signal means, a la Ghostbusters, crossing the streams—or, pushing signal into the red.

*

Pushing into the red. Crossing the streams. Contaminate, and come together. When my brother was still here visiting me in England, he said he wanted to watch a play in London, at one of the more well-known theatres. This was one of his major touristic dreams, along with riding the London Eye. So we took him to the Young Vic to watch the Belarus Free Theatre’s play Minsk, 2011: A Reply to Kathy Acker.

From a New York Times article about the in June 2011, about Belarussians being criminalized for contaminating/coming-together:

Iron-fisted authorities in Belarus have responded to a burst of creative modes of protest by young protesters with a rather surreal innovation of their own: a law that prohibits people from standing together and doing nothing.

A draft law published Friday prohibits the “joint mass presence of citizens in a public place that has been chosen beforehand, including an outdoor space, and at a scheduled time for the purpose of a form of action or inaction that has been planned beforehand and is a form of public expression of the public or political sentiments or protest.â€

Anyone proven to be taking part in such a gathering would be subject to up to 15 days of administrative arrest, the draft says.

When we were waiting for the play to start, some banker or hedge fund manager behind us started plummily talking to a woman, name-dropped Tracey Emin, Jake and Dinos Chapman, started talking about things he’d (he used the pronoun “we”) acquired for booking or selling or something (?? sorry, don’t understand language of millionaire art curating), and then he mentioned that he was a trustee of the Young Vic, where this play was showing, and told the woman, in what I realized was a literally patronizing air, the air of a wealthy patron: “Well, enjoy this!” I wanted to throw up, but then realized it was helpful to be reminded about the relation of money and art and audience and publicity and the public. Had to remember that Jude Law and Harold Pinter and Vivienne Westwood and Mick Jagger and Tom Stoppard and Kevin Spacey and others have publically supported the Belarus Free Theatre, too; that it bears that celebrity-liberal stamp of engagé cool.

The play’s most publicized tagline was, “If scars are sexy, Minsk must be the sexiest city in the world.” And red is a popularly sexy color, too, of course. Is red sexy because people find death sexy, or life sexy, or is it that fragile cusp between, or all of these in one (though I must say, death is not, has never been, sexy to me)?

Towards the beginning of the play, a young man (Denis Tarasenko) gradually stripped off his clothes and showed the various scars received throughout his life. He marked each scar with a red felt marker, both so we could see better where the areas where the scars were located, but also to recreate the scar, the originary cut, then and there, again. Each instance of talking about it, telling us about it, was also an instance of opening it up again, feeling it again, fresh as the first time.

Towards the end of the play, one of the actresses (Yana Rusakevich) stripped naked, and while alternating between a monologue on power, exploitation, repression and sexual and psychic commodification and degradation, and singing a Belarussian folk song with the rest of the actors, was being painted entirely with black ink by the male actors in the troupe. Still speaking/singing, her body was then wrapped in paper and securely tied by the male actors, while one male actor continued to hold the microphone up to her mouth, then as the paper concealed her, through the gap above the improvised packaging, then against the paper itself, where her mouth would have been visible, but was no longer. She continued speaking-singing with increasing fervor, until eventually, reaching the crescendo of her monologue-song, she collapsed/writhed on the floor, still in her paper constraints, until she finally broke out, screaming. Covered in black ink, torso wrapped in paper. Now wielding and cracking a whip, holding a shaking finger to her mouth to tell certain audience members to: “Ssshhh.” Having once been silenced and bundled away, now it was her turn. Her turn to silence and command.

And in that moment you saw the tragic reversal of power that can be produced within an exploitative and repressive system, the life of sexuality and gendered bodiliness under patriarchy, and in particular a totalitarian patriarchy. From vulnerable degraded object-body to whip-wielding silencing (policing) body; from old oppressed to new oppressor. The transformation is no triumph (there is no simple affirmation of feminist self-expression emerging victorious from its oppressive trappings). This, because role-switching alone, without the serious questioning of ingrained and systemic power relations–only I shall be the tyrant this time–isn’t fully or truly emancipatory. But only continues the pain system, and the pain cycle. And she knows it. And we know it.

Red ink, black ink, marker, whip, skin, paper. How do you get out of the pain system? How do you write and rewrite your body, your life, take up the ink and paper, when you’ve been written over and papered over, over and over again? When the story’s been already written for you, over and over again, and always without your consent?

At the beginning of the play, a man in the audience loudly responded directly to the actors; we all turned to him, most of us probably thought he was part of the performance. He wasn’t, it turned out. At the end of the play, while the troupe was taking their bows, the same man–an older man in a button-up and crewneck sweater–stood in the aisle, his back turned to the actors and told everyone in the audience: “I AM BELARUS.”

He went on to say that the actors were insulting his country, that this was all lies, this is political provocation, and they receive money (here he trailed off vaguely). Then he walked away, out of the small theatre, to boos from the audience.

“I am Belarus,” he had said. The implication of course being that only some people get to “be” a nation, represent a nation, show the right face to the nation. The queers and sex workers, the scarred men and dirty women: their stories have to be erased, silenced; they’re not valid, they “corrupt” and “pollute” the healthy, upright patriotic body. The only body meant to exist, to show its face, its flesh. As women and queers and people of color, you often get (I’ve often gotten) that feeling even within radical leftist and anarchist movements. Women and queers and people of color are habitually made suspect, derided, for their frivolous, impure, soft-power, identity-centered concerns; they can’t just be good, straightforward (phallically-directed, get to the point, the real point is) revolutionaries, all unanimously and unquestioningly fighting for the One Good Cause–typically anti-capitalist, anti-war, and based on the (traditional, white, hetero) working-class. No: the others carry too much baggage with them, it prevents cohesion, they have too many issues, they divert the struggle. But why shouldn’t the struggle be diverted (diverse), perverted, impure, contaminated? This continued unacknowledged pretense at unity-as-homogeneity only reinforces the kind of binaries that we must strive (and rejoice) to dismantle.

Minsk, 2011. That title: name the place, name the time, this happened, our lives are real; the way Derrida writes, talking about Paul Celan who often dated his poems, that the date is a cut: ““We will therefore focus on the date as a cut or incision that the poem bears in its body like a memory, sometimes several memories in one, the mark of a provenance, of a place and of a time. To speak of an incision or cut is to say that the poem is first cut into there [s’y entame]: it begins in the wounding of its date.â€

One of the most used props in the play was a shaggy red carpet, which eventually became a bit dirty by the end of the performance, fake snow and paper and black ink. Dirty, or more accurately: lived-in. Lived-in red. Sometimes this red carpet was sometimes a long puddle of blood at the site of the 2011 terrorist attack in the Belarus metro; sometimes a red carpet. For the penultimate scene, it became a river into which all the actors in the troupe dipped their feet, pointing into the distance and saying they could glimpse Minsk. In this scene, each actor gave a short monologue about her or his personal circumstances: the arrests, the life of political exile, being fired from jobs, the daughter back home waiting, breaking up with a lover, being beaten, falling in love. With their feet splashing in this red, red, shaggy river.

And for the final scene, the red carpet eventually became a kind of curtain, which the actors gradually lifted to conceal themselves, as they sang another Belarussian folk song, with eventually only their eyes and feet visible. I loved that, rather than the more traditional red curtain whooshing over the stage, powered by some invisible force, to end the show and obscure the actors entirely from view, they were covering themselves, with their own red curtain, and even then not perfectly, not totally (the parts of their bodies that still showed).

This jointly held red curtain/carpet, which was also: a cut, a wound. A zoomed-in close-up of a cut: clotty, clumping, bright red. A cut that didn’t cut away (like a filmic jump-cut at the end of a film), but rather, a cut that opened. When the carpet was a river that the actors dipped their feet into as they told their own stories–even then the red carpet was already a wound. Telling their stories, showing their wounds; when Tarasenko told his scar-stories at the beginning, marking his body with red ink. Such scenes didn’t just break the fourth wall, but replaced the wall entirely with a wound. A replacement of the old barrier with: an opening.

This opening up of a redness, this act of holding up and going deep into the red carpet (which had appeared in nearly every scene of the play) came just as they were “closing” the show. As if to say: this performance may end now (cut!), but think also of what it opens, what it cuts open, what it exposes. Ending with an opening. An act of hiding that is also an act of revelation, exposure; as an underground theatre must always hide and expose at the same time. Its hiddenness makes its exposure possible. (The ways in which the play was explicit: explicitus est liber, explicitus est fabula, explicitus est cruor. The book, the play, the blood. Is unrolled. Is made explicit.)

As the actors slowly hid themselves behind the red carpet, it felt as though they were at the same time: revealing themselves. Exposing a wound. Blowing it up. Going deep into it. Into its dirty red blood. It was contaminated. It was lived-in.

*

Minh-ha:

Power is at once repulsive and intoxicating. Oppositional practices which thrive on binary thinking have always worked at preserving the old dichotomy of oppressor and oppressed, even though it has become more and more difficult today to establish a safe line between the government and the people, or the institution and and the individual. When it is a question of desire and power, there are no possible short-cuts in dealing with the system of rationality that imprisons both the body politic and the people, and regulates their relationship. There are, in other words, no ‘innocent people,’ no subjects untouched in the play of power.

…’impurity’ is the interval in which the impure subject is feared and alienated. It is the state in which the issue of gender prevails, for if red defies all literal, male-centered elucidation, it is because it intimately belongs to women’s domain, in other words, to women’s struggles. To say this is simply to recognize that the impure subject cannot but challenge hegemonic divisions and boundaries. Bound to other marginalized groups, women are often ‘impure’ because their red necessarily exceeds totalized discourses. In a society where they remain constantly at odds on occupied territories, women can only situate their social spaces precariously on the interstices of diverse systems of ownership. Their elsewhere is never a pure elsewhere, but only a no-escape elsewhere, an elsewhere-within-here that enters in at the same time as it breaks with the circle of omnispectatorship, in which women always incur the risk of remaining endlessly a spectator, whether to an object, an event, an attribute, a duty, an adherence, a classification, or a social process. The challenge of modifying frontiers is also that of producing a situated, shifting, and contingent difference in which the only constant is the emphasis on the irresistible to-and-fro movement across (sexual and political) boundaries: margins and centers, red and white. It has often been noted that in China ink painting there is a ‘lack of interest in natural color.’ One day, someone asked a painter why he painted his bamboos in red. When the painter replied ‘What color should they be?,’ the answer came: ‘Black, of course.’

*

Jarman wrote “On Seeing Red.” Minh-ha mentioned that seeing red is a matter of reading, so: “On Reading Red”? But I would write: “On Feeling Red.” Feeling red’s perceptible-imperceptible signal. Its frequency in the body and the world. How frequent it is, in the body-world and in the world-body. I’m feeling it, do you feel it? I feel you, do you feel me? When I ask you, Do you feel me?, the question is red.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)