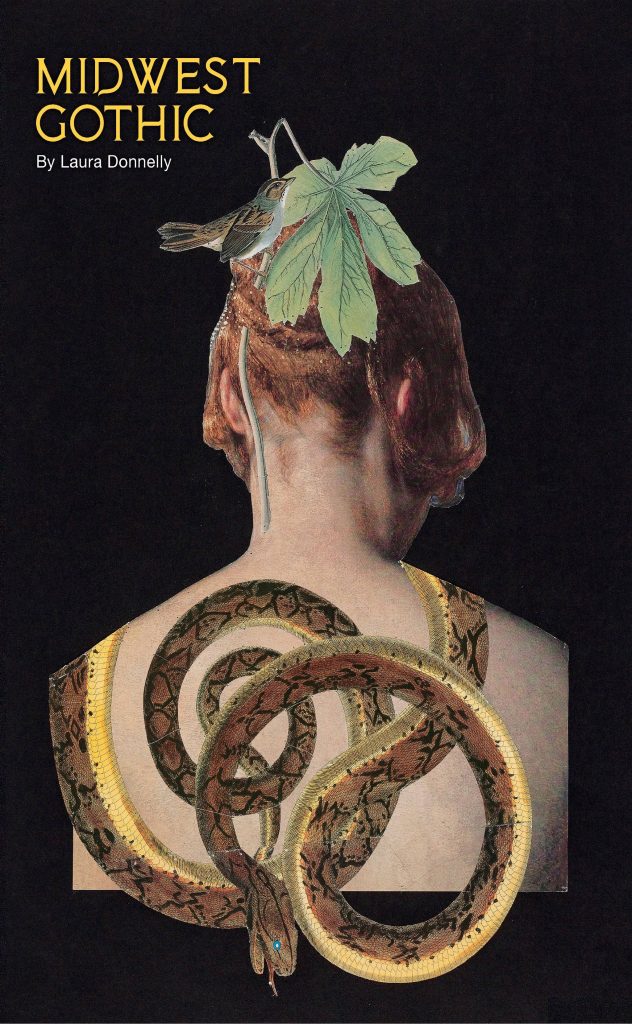

(Ashland Poetry Press, 2020)

REVIEW BY SALLY SMITS MASTEN

—

The intertwining of poetry and gardens has a long history, of course, from the pastorals of Hesiod and Virgil to Wordsworth’s daffodils to Anne Spencer’s famous garden and Mary Oliver’s incantatory natural imagery. And it isn’t new to say that a poetry collection is like a garden, and yet.

And yet. Laura Donnelly’s Midwest Gothic is the garden of Eden and of exile, the garden of inheritance and of renewal. Each poem in the collection shows her to be a master gardener, deftly pruning the lines, digging into the hard ground, nurturing delicate images, unearthing what’s buried, replanting seeds of hope after sorrow. Midwest Gothic is inventive, smart, poignant, delicate, sometimes bitingly funny, celebratory, sorrowful. With skill and sincerity, Donnelly deploys the garden, the world of the garden, in all directions—as metaphor and motif, image and symbol. In the gardens are the threads between generations, the living representation of her mother’s courageous act(s), the illustration of the difficulty of starting over and eventual triumphs, the image of the roots of family and also the burial of ancestors and the burial of secrets. As Donnelly writes in “Summer,” the book’s final poem, “It was all garden / and it was all not.”

For the first section of the book, Donnelly’s first poem provides a framework and an aim: “I will gather you back.” This first section, then, becomes an unearthing, a recovery, a way of preserving stories and memories and establishing the ground from which the speaker comes. These poems meditate on inheritance—they revisit graveyards and basements, old homesteads, tangible hand-me-downs, and her great-grandmother’s written account of her childhood.

In the most striking poems, Donnelly draws together the stories of her ancestors with meditative, prayerful language and juxtapositions from the garden: death and glory, rot and beauty, the quotidian and transcendent. In “Alice at Five Years Old,” for example, Donnelly moves from a single photograph of her great-grandmother’s family on their homestead to a handed-down memory: “Someday, when the girl meets / her mother-in-law / they’ll share a bowl of oatmeal / as if it’s the body of Christ.” The poem concludes with the contrast of death and renewal in language with resonant, sorrowful long O sounds, an incantation and prayer: “Hear us, oh Lord, in our longest day’s / shadow of bones— // the delphinium grows / from her body / in a choir of indigo.” Similarly, in “Primula vulgaris (Primrose)”—even the title drawing together contrasting language—the speaker digs into the difficult work of gardening first, with “compost, manure, / the pulverized feathers of chickens,” and abruptly shifts to the difficult work of living:

Grandmother does not want to leave

her house for the nursing home.

Mother does not want to leave

her house for the divorce.

In the next two stanzas, the speaker continues working through this cycle of death and rebirth, a frost and roots exposed, a struggle to stay alive, the fuchsia’s centers “bright as slits of flame.” This poem is rooted in earth, in “blood and bone,” dwelling on this symbolic burial of the birds’ “remains.” But just as in the paradox of that word, the poem is insistent on remaining, on staying alive, on growing from these roots.

While individual poems certainly stand out, the particular brilliance of this section—and indeed the whole book—is in its careful arrangement, Just as a gardener understands how to pair plants so that each thrives, these poems resonate with one another, echoing refrains and images to build a story, a full and blooming world, creating layers and depth of meaning.

The second section digs closer to the surface with more intimate meditations on childhood, what was observed, what images remain, what meaning to make now of what happened then. A particularly striking pair of poems appear almost at the midpoint of the book, “Transplanting the Flowers” and “Garden Vernacular,” and between them, Donnelly creates a shift in momentum. There is something like an electric current moving between these two poems. “Transplanting the Flowers” is a visceral reflection on the speaker’s mother, returning to her house four months after leaving the house and the speaker’s father; in the imagery and line breaks here, again, is an insistence on thriving in spite of it all, on preserving the inheritance that is a source of life:

What she won’t leave behind:

a poor woman’s dowry, the perennials

separated, transplanted,

passed down.

But the poem’s end is uncertain; the act of transplanting—the perennials, her own family—is filled with suffering: the spade “slices root,” rips and tears, with an unraveling of roots like thread.

The poem that immediately follows, however, points toward the garden, in its new unlikely place—“strange on a city block”—thriving. There are “gloriosa daisies between cracks” and “ferns lapping up the dusky shade.” In this poem is the transcendent moment of hope, after all the quotidian and tedious work of living, after the difficulty of separating, of loss. The garden, like the speaker and the reader, find restoration and even magic in the final lines: “It was not unusual to see bear cubs / in that garden. It was not unusual // to see that garden breathe.”

In the third section of the book, Donnelly’s masterpiece is in choosing exactly the right source and exactly the right method; these are “The Secret Garden Erasures.” Donnelly works with this classic of childhood, makes this inheritance her own, releases, like her mother’s garden, its secrets, and unearths new meaning from it. In this section, too, are echoes of the previous sections; it becomes a kind of mirror for the speaker, a new way to understand her history. Here, too, is a breathing garden; here, too, are flowers named and blooming. It ends, perfectly: “I thought / I could dig somewhere.”

The final section of the book moves beyond the boundaries of the garden, family history, and the speaker’s inheritance; true to the title of one poem, “Theme and Variations,” it keeps contact with its roots, in poems like “Perennial” and “Calendula officinalis (Marigold),” but its tendrils spread outward, in content and form. Here, there is a pantoum, sparse and musical couplets, layered meditations on summer, the “flesh and saturation” of tomatoes, knives in kitchens and surgeries. And there are more directly confessional poems, contrasting forgiveness with a “bitter twang in [her] throat.” In an echo of “Garden Vernacular,” the poems now, rather than the garden, tend the speaker’s family secrets, transforming sorrow and anger into sharply drawn images and language.

Donnelly’s book is an inheritance—of family mythology and secrets, the knowledge and language of gardens, and musical and literary traditions. In 1972, Adrienne Rich published a review of Eleanor Ross Taylor’s work, noting that her poems “speak of the underground life of women…the woman-writer, the woman in the family, coping, hoarding, preserving, observing, keeping up appearances, seeing through the myths and hypocrisies, nursing the sick, conspiring with sister-women, possessed of a will to survive and to see others survive.” Donnelly has continued in this tradition, sustaining and nurturing it, and adding her own sheer intelligence, deep reflection, delicate phrasing, sharp imagery, and deft and resonant deployment of metaphor and motif. The poems dig deep for their thriving roots; they do not shy away from “blood and bone” in the soil and the difficult work of unearthing. And then, they are carefully placed in the book’s garden plot, and both individually and together, these poems create a flourishing, brilliant collection.

—

Sally Smits Masten’s poems have been published in Crab Orchard Review, The Georgia Review, Smartish Pace, Northwords, The Laurel Review, and other journals. She earned her MFA in poetry from the University of North Carolina Wilmington and her PhD in American literature from The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She currently teaches at Western Governors University.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)