Publisher: Catapult

Publication date: November 1, 2016

Number of pages: 276

Price: $15.25

REVIEWED BY Mandy Shunarrah

—

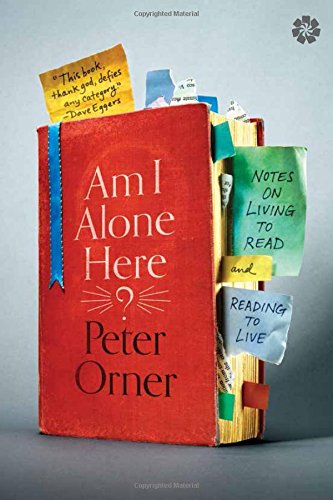

To label Am I Alone Here? as any one genre is to do it and the reader an injustice. Part memoir, part literary criticism, and all love letter to literature, Peter Orner’s essay collection is the kind of book readers can’t help but cherish. My copy of Am I Alone Here? has as many flags and sticky notes as the stylized book on the collection’s cover. I read it with splendor.

With each essay, Orner measures his life in books—namely how, as a book lover, the literature he’s reading informs and intersects with his life. Reading is the lens by which Orner looks back on teaching law in Prague, the dissolution of his relationship with his ex wife, and his now-deceased, emotionally unavailable dad who haunts the stories like the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Bibliophiles will recognize the seamless neural connections that inextricably link existence and books in each piece.

You need not have read all the books and authors Orner mentions to appreciate the resounding influence literature has had on his life. He only tells you what you need to know to understand each essay and doesn’t burden the reader with extraneous details. Even if you haven’t read the stories the essays hinge upon, you get the impression you’d enjoy them just as much as Orner does. In none of these essays is Orner attempting to prove a supposed superior taste in literature—you can tell he genuinely delights in these stories and wants to share them with others who might enjoy them, too.

When you read Am I Alone Here? you feel as though you’ve read a hundred books and lived as many lives. For bibliophiles, the question of whether we are alone here is a rhetorical one: a question we ask ourselves with every book we read. The question “Am I alone here?” is at the heart of why we read and why literature is an art essential to life.

I talked to Peter about his reverence for the written word and the process of writing his first full-length work of nonfiction. (This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.)

Mandy Shunnarah: Tell me about how these essays came to be. Since this essay collection bends genres and your past works are fiction, I’m curious to know if these essays poured forth organically or if a change of direction was something you’d been planning.

Peter Orner: Writing, any kind of writing, is hard for me. I’ve always felt it was like squeezing blood from a stone. These essays began (and ended too) with me sort of talking to myself in the very early hours of the morning. I think of them as morning notes to myself. I never plan very much. But after a certain point I realized these notes were speaking to each other.

MS: When you would discuss where you were in your life at the time you were reading a particular book or story, I believe the youngest age you mentioned was 19. Were there any books you felt a connection to before that time?

PO: You know that book about the little bird who’s born while his mother is off getting food? And he flies around asking every other animal and a bulldozer, too, if they are his mother? [Are You My Mother? by P.D. Eastman] I remember holding that book and wanting to hear it again and again. What a sad, beautiful book that is. I think it all started with that one. What would a psychologist do with this answer?

MS: It’s clear you’re an expansive reader. Was it difficult to choose what authors and stories you would include in the book? Are there other books you’re deeply fond of that didn’t get mentioned in your essays?

PO: So, so many. In the introduction to the book I list a few including Bessie Head (wonderful, deadly writer from South Africa/Botswana), Evan Connel (the great story writer from Kansas City), Calvert Casey (a Cuban Irish story writer), and Penelope Fitzgerald (the British novelist whose work, all of it, floors me)…There is also a piece I’ve been working on in my head about Primo Levi for many years about reading Levi in a cemetery in Bolinas, California. One day I’ll actually write it. Or maybe not; it is better in my head.

MS: Since completing Am I Alone Here? have you read anything you wished you’d read sooner so it could’ve been included in the collection?

PO: I recently read Patrick Modiano’s weird memoir, Pedigree, and took a lot of notes in the margins. Got me thinking. And earlier this year I discovered the work of the American story writer and novelist William Goyen. Goyen’s been largely forgotten. He deserves some serious resurrection because he’s an original. He’s fearlessly vague, and like Modiano, obsessed with memory.

MS: Your contentious relationship with your deceased father is a recurring theme in many of the essays. Did writing about him after his passing help you understand him in a way that wasn’t possible while he was alive?

PO: I wish I did. I think I’m more confused about him than ever. But I’m suspicious of answers in general, and much prefer questions. Will I ever get to the bottom of the strange person who was my father? Probably not. Writing about him made that question less even less answerable.

MS: What are you working on next? Since you’re primarily a fiction writer, do you anticipate writing nonfiction again in the future?

PO: This will be my last book that incorporates specific aspects of my own life—he said, hoping it was true. I live and die by fiction… But in a way nonfiction is just fiction with a little more literal facts. Either way, like I say, it’s all hard for me.

—

Mandy Shunnarah is a writer based in Columbus, Ohio, though she calls Birmingham, Alabama, home. She writes personal essays, book news, and historical fiction. Her writing has been published in The Missing Slate, Entropy Magazine, PANK Magazine and Deep South Magazine. You can find more of her work at her website, offthebeatenshelf.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)