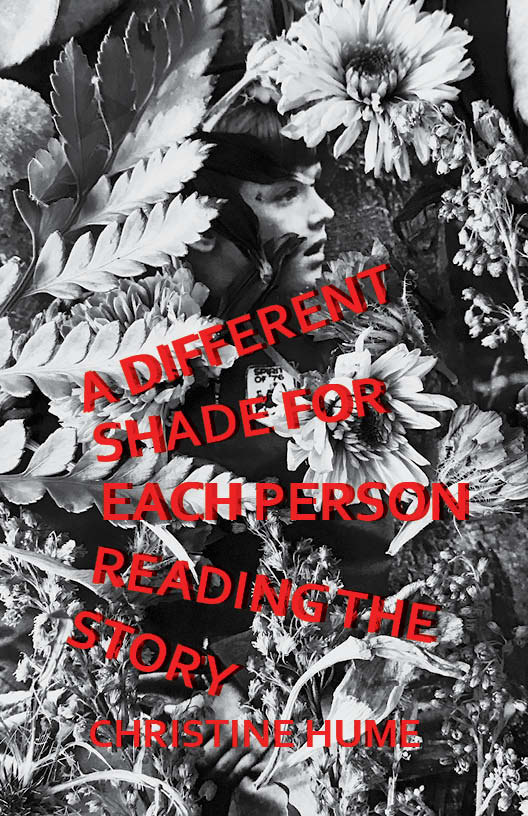

[PANK] Team Member Emily McLaughlin sat down with [PANK] Author Christine Hume about her new essay collection, A Different Shade for Each Person Reading the Story. Buy it HERE

We could not be more pleased to announce the April release of Christine Hume’s little book A Different Shade for Each Person Reading the Story, a disability-forward essay that melds memoir, neurology, chromopoetics, and literary criticism into an ecstatic embodiment of an illiterate girlhood. Shaped as an index, rather than a primary text, Hume posits the cruel optimism of reading, which promises to shape brains and lives, against the dyslexic’s subterfuge intelligence. In vignettes, meditations, lapses, guesses, and fragments, all refracted through the color red, this work questions what reading means and how we come to claim it.

PANK: Thank you for talking to us about A Different Shade For Each Person Reading The Story. PANK is so fortunate to publish such a wonder.

CH: I’m the fortunate one!

PANK: A Different Shade For Each Person Reading The Story does read like a bit of a mystery, like what learning to read as an avid reader and writer with dyslexia might experience? And it feels ever-growing, still alive. Does it feel like more of a poem to you? Are you able to say where it began? With which piece? With which vignette, fragment, guess?

CH: The process of writing this chapbook was extended, evolving and shifting over seven years. I certainly didn’t set out to write it; I resisted it even as I felt compelled toward it. I had been writing a long essay about my girlhood refigured by the color red when my daughter was diagnosed with dyslexia. I read a bunch of books about dyslexia and a bunch of other books about color or color theory. Both groups of books were missing a crucial sense of subjectivity and interiority. The books about color were often shallow lists of dazzling facts and stories; somehow most art historians, for instance, manage to kill the use of color in visual art by a thousand dull knives. They miss color as an experience, bodily and aesthetic, which is, to me, the point. Most of the books I read about dyslexia were like self help books, or information-driven, which I often appreciated, but never felt connected to emotionally. Eventually, the red girlhood essay split in two, with a lot of fall out. Much of this had to do with my enlarged capacity to face my own dyslexia indirectly through my daughter’s–and reviewing my life through its lens. New memories returned involuntarily, and so did some of the research I did 20 some years ago in grad school–on John Keats and Charlotte Bronte. I also liked the homophonic relation of red to read (past tense) because reading for me has always been auditory and mistake riddled. Red itself was my lead. I didn’t know what I was writing, red was leading me somewhere. Red coalesced the shame and embarrassment as well as the libidinal thrill and material pleasures of reading. You are right, it definitely could keep growing, but I pared it back instead. Once I realized what I was doing, it was more the work of assembly and arrangement. I left shades and stories out; I made it elliptical and suggestive; I made it look like a series of prose poems, relying on white space and gestalt. If it feels like poetry, it’s because dyslexics often think in poetic modes–in images, gaps and materialities–and read best in short discrete chunks that activate our imaginations, that require readerly involvement. I was trying to make a dyslexic-friendly text, more than I was trying to write an essay or a serial poem.

PANK: This leads me into my next question about your use of chromopoetics here. Can you tell us more about it?

CH: I teach a creative writing class I call Chromopoetics. In class, we write with, about, through, and into color, a visual phenomenon that seems to elude linguistic expression. Have you ever tried to describe a color or represent it in language? It’s difficult, and that difficulty is a good place to sharpen writerly skills. It’s a class that studies the poetics of color, but it is also by necessity an exploration of queerness, excess, narcosis, superficiality, memory, alienation, and meaning itself. We get together with the Art Theory class and trade ideas, language, and projects; we mix and complement and contrast. We follow chromatic whims, but we also look at a lot of art, fashion, photography as well as listen to music/sound art and go on color walks. I came across the term, “chromopoetics,” maybe hyphenated as “chromo-poetics,” in an interview with Brazillian artist, Cido Meireles, whose work I also teach in class. As far as I know he coined the term. In context, he uses the word to insist that we don’t reduce his work to didactic political or symbolic meanings, but that we leave ourselves open to the work’s chromopoetics, its allegiance to perception, sensitization, mystery, phantom textures, affective intimacies–complex experience!–that does not cancel out the political but augments it. Partly, he’s correcting the dogged perception that Meireles and other Latin American Conceptual artists face because of their relative political awareness and acuity (compared to most western European and North American Conceptual work). I find the term useful for thinking about a canon of literature that employs color to do both symbolic and poetic work, each extending the reach of the other. Some work I include in this canon: Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child, Han Kang’s The White Book, Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red; Marie Ndiaye’s Self-Portrait in Green; Harryette Mullen’s Trimmings, Gerturde Stein’s Tender Buttons, Wayne Koestenbaum’s Pink Trance, William Gass’s On Being Blue, Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, Porochista Khakpour’s Brown Album, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, and shorter works such as Kevin Killian’s “Color in Darkness,” Lisa Robertson, “How to Colour” Samantha Hunt’s “The Yellow,” N. Scott Momaday “The Colors of Night,” David Foster Wallace’s “Church Not Made of Hands,” “Everything is Green,” and “Brief Interview #42” — and a lot of poetry. I include non-contemporary works as well–like Moby Dick’s whiteness as well as Jane Eyre’s scarlet curtains–but since this is a creative writing class, we focus on more recent work. In class, we explore the ways that language colors our perceptions, the ways that color situates language, the ways that we see through language and color, the ways that color and language are similarly contexted dependent as well as context-creating–manifesting moods, structures of feeling, politics, and poetics.

PANK: And so was it difficult at all to settle on the color choices for each piece?

CH: I did a lot of interesting and unnecessary research that helped ground my choices, often in ways that aren’t readily available. I mixed the names of reds from a variety of disciplines with my own inventions, trying to let the subjectivity of the shades guide me. I was thinking about the philosophical counterexample that David Hume poses to his own empirical theories, one that resonates with the magic trick of reading for me. He says, presented with a spectrum of blues with one shade missing, we can form an idea of this missing shade even if we have never had a prior impression of it. In other words, we can generate an idea without first being exposed to the relevant sensory experience. In this case, the system of colors forms a space in which gaps can be recognized and, if not too small, can be filled in. Color systems always leave something out as they attempt to totalize; it’s a lovely kind of desperation, like memory itself.

PANK: Early on, in the fifth piece, you write, “Does reading take place in one person’s consciousness or out there, in a system that separates you from me?” You also refer to yourself as a closeted dyslexic. Was this as liberating to write as I assume vulnerable? You refer to yourself as a closeted dyslexic, was this book the first time you have revealed your struggles with dyslexia publicly?

CH: Finding out in late college allowed me to grieve a little and shrug it off. I had already absorbed a toxic amount of shame and figured out ways of getting by and working around my disability. I never allowed myself to be curious about my condition. I never identified as dyslexic. It took my daughter’s diagnosis her then tutor asking me to give a presentation to the local chapter of the Dyslexia Association to really start thinking about how my life and writing have been shaped by dyslexia. I had only told a handful of people in my life at that point. I had habitualized avoidance. Not of reading, but of exploring my relation to reading. No way was I going to reflect on a bottomless pit of pain, but then the thought of talking to reading tutors, for whom dyslexia was common and surmountable, gave me a chance to push beyond my fear. That presentation set me up to re-imagine my entire life through this new lens. I’m grateful to my daughter’s tutor, Madelon Possely, who invited me. The women in her group were incredibly supportive and curious, asked wonderful questions and offered thrilling insights. I couldn’t stop thinking about their questions and about how my own writing was (unwittingly! unbeknownst to me!) had been cryptically addressing dyslexia all along. Discovering the subtext or the true subject of some of those poems was liberating. For instance, the first poem in my second book uses a list of “comprehension questions” to imply a narrative. I wrote this remembering my habit of skipping the reading passage on standardized tests and jumping right to the questions. Often, the answers seemed loaded in the questions; they were leading questions or they pointed to their answers somehow. This was a compensation strategy; it was also a way of reading the questions as a kind of poem, where a lot of the narrative is suggested indirectly. I’m not answering your question, though, not even indirectly! A Different Shade… was definitely my first public outing. After writing it, I remember the first time I mentioned being dsylexic to students. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I dropped the word and owned it in a small graduate class. At the end of the semester, a really inspiring and dear student surprised me with a handmade card in which she thanked me for talking casually about a learning disability in class, making it seem normal and easy. I was floored. It was a kind of first for both of us, releasing us at least momentarily from the grips of useless but deeply felt impostor syndrome.

PANK: Your profound “Maroon” vignette is hard to summarize. You tell us how your mother might call a neighbor a maroon, meaning moron. “The word “moron,” itself coined by a psychologist in the early 1900s, performs its own meaning when misread or mispronounced . . . To equate “moron” with “maroon” though implies a sonic relationship between abandonment and idiocy. To be illiterate is to feel marooned, isolated, left. It took humans two thousand years to develop literacy, and now we give a new human about two thousand days until we expect her to start reading . . . if you consider the other meaning of Maroon—an escaped slave living in the Caribbean—you see how abandonment is just what you chose to ignore, an oxymoron.” I’m botching this, but wow. This piece seems to encapsulate what your entire book is about, the experience of reading and the experience of being misunderstood as a different type of reader?

CH: Language is always on the move. Parents make themselves the object of scorn to their children with their outdated language, which is always linked to outdated ideas. After 1880s with the invention of factory dyes, red goes from a rare royal luxury, a symbol of wealth and power, to cheap in every sense of the word: vulgar, suspect, crass, risky. Only in the 19th century did red acquire racial connotations in the Western world via (1) the “red Indian,” (2) “Carmen,” the novella and opera from carmine the color cochineal insects produce, and (3) “maroon,” a runaway slave from the late 17th century (a word produced from marron meaning “feral” in French and/or cimarron meaning “wild place” in Spanish). Because red is one of our longest named colors in English, its history comes loaded with ideology and metaphor. It drags its dinosaur tail of meaning into the present, which creates the conditions for misunderstanding. Or understanding something unintended, other kinds of knowledge.

PANK: And “Estrus Red” too movingly meditates on so many things. How did you settle on this title and or each title?

CH: I meant to evoke the idea of being in “heat,” a biological cycle when the female is suddenly very visible. The blood is menstrual blood here, and I want to link reading with receptivity, fertility as well as erotic pursuit. That feeling of visceral absorption and chasing language wherever it leads; texts that get freaky with you and get you sprung but slowly–all the chemistry that marinates your body while you read. Reading is fully biological. We must change our brains, rewire our minds, in order to see marks on a page as readable text. And reading allows us to be penetrated by another mind, another biology, another rhythmic pulse.

PANK: You tell us here, “Anyone who has ever felt bereft upon finishing a book understands this transformation, which is both temporary and, in some measure, permanent: you can’t go back, you have changed.” You seem to be summarizing your own book here. Any reader of this can never go back to thinking of dyslexia, of reading, or of the color red, in the same way again. You have changed our experience of all of these things. Was this your authorial intent or did you have intentions you were aware of when writing?

CH: Thanks, that’s great to hear! I didn’t have that [transformation] specifically in mind, but of course what “finishing a book” there means–writing one or reading one?–is ambiguous. Maybe because reading was such an arduous activity for me early on that the effort of reading a book felt akin to writing it, or so I imagined.

PANK: Readers can experience your experience and see things in a new way with each fresh read, the way you might have learned to see words on the page. With the index of shades of red, each shade catches your eye in the periphery from another angle. To you, is there an ideal way for the way this book should be read or do you have an ideal reader in mind? That may seem counter-intuitive, is there a way you would like this book to be taught to writing students? Or, what I am trying to say here, perhaps, is in thinking of this as a rethinking of the cruel optimism of reading, is there an optimistic way you would teach this book to writing students, or a different way to teach this book to students with disabilities?

CH: I love this question, thank you! I included the opening “Instructions” after feedback from readers at DSQ [Disabilities Studies Quarterly], who because I think it’s a mostly scholarly venue, needed some framing for the piece. (An excerpt was published there last year.) I thought their request was an opportunity to say why I didn’t want to introduce or conclude the piece. I wanted readers to have to figure out what was going on as a kind of simulation of the dyslexic experience, not an exact replication of it, but an experience that involves piecemeal figuring and patience. The “Instructions” make clear that there is no ideal way to read the work, and encourages reading as a heterogeneous activity, and not an entirely standardardized act. As much as our education system has been co-opted by capitalism and has become a kind of factory for manufacturing readers (K-3rd grade), human difference prevails. Our brains are not all wired the same way. Many of the dyslexics I know started reading well after 3rd grade! None of them ended up in prison as is the rumor about people who don’t read by 3rd grade, though I also know that prisons hold a statistically high number of people with learning disabilities. Reading itself is not a measure of intelligence, but we treat it that way. In an ideal world, I would have used the dyslexie font (weighted font that’s easier for people with dyslexia to read), perforated all the (unpaginated) pages, and included a link to the free audio book version.

PANK: That’s next on PANK’s list. Thank you for your time, Christine. PANK loves you!

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)