(Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2018)

REVIEW BY MIKE CORRAO

—

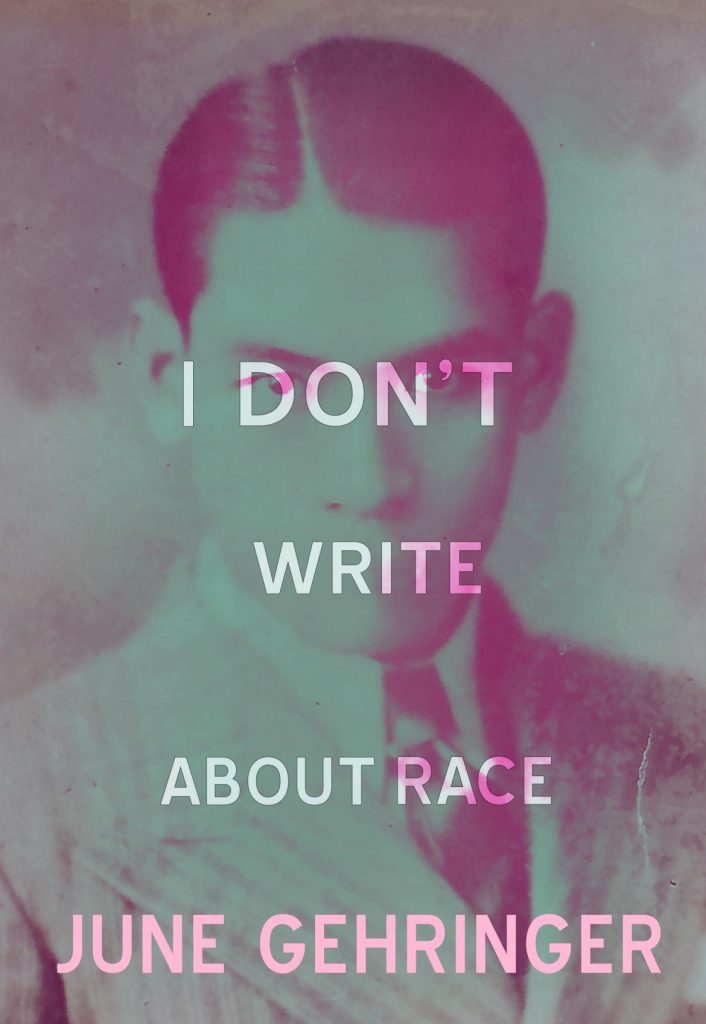

I Don’t Write About Race is a beautiful and honest collection of poems, exploring the complex and nuanced nature of identity. “I don’t write about race / I write about erasure,” the poet says.

Gehringer’s work feels so natural and cohesive, as if it is forming on the pages as you read. Each new poem, a continuation of the last. The poet documents what’s inside her head, as well as a cacophony of microaggressions, which occur so often as to become another of life’s mundanities. The reader is confronted by their own actions. We are made to witness the constant judgement and dehumanization of the trans community. Moments where they are misgendered, belittled, harassed, and ignored.

For a brief time, the poet wishes for some physical manifestation of these pains (a burn or a cut or a bruise), somewhere she can point to and say, ‘this is where it hurts’ but the pain in these poems is often abstract. It is emotional and psychological. How do you alleviate the pain of being considered less of person than you are? The pain of ‘white hands’ and violent rhetoric? “How many millions wish you dead?”

In the latter half of her collection, Gehringer shifts focus, labeling many pieces as Leviathan. In doing so, the poet emboldens her work. She summons this image of the ‘eidolon from a long-lost age’ and imbues it with new meaning. The subject becomes large and powerful. Yet in the process, she does not change who she is. She does not make herself in the likeness of this new image, rather the Leviathan becomes her.

Gehringer has created a powerful collection of poems. I Don’t Write About Race is essential reading, an important text exploring identity and the trans experience.

—

Mike Corrao is a young writer working out of Minneapolis. His work has been featured in publications such as Entropy, decomP, Cleaver, and Fanzine. His first novel will be released in fall of 2018 by Orson’s Publishing. Further information at www.mikecorrao.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)