INTERVIEW BY GABINO IGLESIAS

–

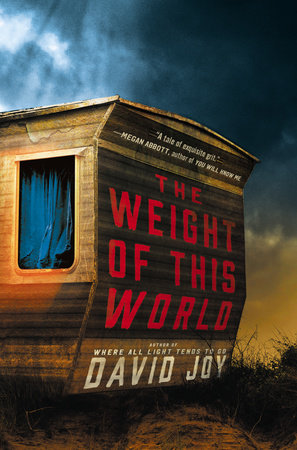

I read a lot of crime, but few novels impress me so much that I find myself still talking about them six months after turning the last page. David Joy’s The Weight of This World belongs to that small group. While the combination of grit, superb storytelling, violence, and beauty make this novel a must-read, Joy is also a pleasure to talk to, so I decided to dig a little deeper into some of his passion, his writing, and books in general. Here’s what he had to say.

GI: The Weight of This World is beautifully written, but it’s also packed with enough brutality to satisfy fans of horror fiction. How do you achieve such a wonderful balance?

DJ: As far as balance, I think that largely comes from the writers who most influenced my work. I remember the first time I read William Gay’s short story, “The Paper-Hanger,” which is one of the most disturbingly violent stories I’ve ever read, but I was blown away by the beauty of his prose. There are lines in that story where he’s describing a murdered child in a freezer, lines like, “Ice crystals snared in the hair like windy snowflakes whirled there, in the lashes,” where Gay is very deliberately creating that play between beauty and horror. I think ultimately he’s doing this in order to make the violence more palatable. If you can achieve the right balance you can coax a reader through all sorts of darkness.

With the comparison to horror, I think that boils down to the realism of the violence. I don’t hold back or shy away from presenting something exactly as it is. There is no grace in dying. I don’t live in some fantasy world where people double over from gunshots and writhe then still like the old cheesy Westerns. At the same time, my work certainly isn’t gratuitous. There is a very real danger in sugarcoating violence, in repeating that John Wayne bullshit that glorifies and dismisses the act of killing as something trivial and easy. This isn’t violence for violence’s sake. I’m making very deliberate choices. In Where All Light Tends To Go, I had an eighteen-year-old narrator who was ill equipped for the violence he found himself surrounded by. I wanted the reader to experience what’s happening with the same sort of shock as the character. With The Weight Of This World, that novel is very much a sort of treatise on violence. I want the reader to walk through the blood. I want to force them to confront it and to ask big questions.

I think Dave Grossman’s On Killing is one of the most important books ever written about violence. Everyone should read that book, but especially anyone who is going to write about violence and the act of killing. Anyways, there’s a passage early on in that book where he writes, “They are things that we would rather turn away from, but Carl von Clausewitz warned that ‘it is to no purpose, it is even against one’s better interest, to turn away from the consideration of the affair because the horror of its elements excites repugnance.’ Bruno Bettelheim, a survivor of the Nazi death camps, argues that the root of our failure to deal with violence lies in our refusal to face up to it. We deny our fascination with the ‘dark beauty of violence,’ and we condemn aggression and repress it rather than look at it squarely and try to understand and control it.”

That’s why it’s so important to present violence in all its horrible ugliness, because only through capturing that reality can we start to have real, meaningful conversations about it.

GI: There is enough great literature coming from Appalachia to keep readers away from New York white-rich-straight-male-finds-himself-in-Brooklyn narratives for years to come. What is your role in that movement? Do you even consider it that?

DJ: Michael Farris Smith and I have talked about this a lot, about the void that was left in the South over the last few decades. We lost so many writers in just a few short years—Barry Hannah, Larry Brown, William Gay, Eudora Welty, Harry Crews, Tim McLaurin. I think if there is a movement, that’s what it’s a reaction to; it’s a matter of doing our damnedest to fill that void. When it all boils down to it, those are the writers who influenced me most. I’m rooted in writers like Ron Rash, George Singleton, Lee Smith, Daniel Wallace, Brad Watson, Jill McCorkle, Silas House, Tommy Franklin, and so on. I think for all of the writers who’ve emerged out of the South and out of Appalachia over the past five or ten years, those are the people whose footsteps we’re following. You come out of a place like this and whether you like it or not you stand within a shadow. You stand in a shadow cast by everyone before you and all you can hope is that your work lengthens it, that at the end of the day your work adds to that conversation.

GI: You’re a mountain man and I’m from a barrio near the beach, but it seems like we both grew up surrounded by struggle and a rich storytelling tradition. How does that upbringing shape your prose now?

DJ: I very much ascribe to that Cormac McCarthy belief that, “The core of literature is the idea of tragedy.” I think bearing witness to struggle can, as hard as it is at the time, make for damn rich ground to mine. We’re not talking about not getting the car you wanted for your sixteenth birthday, or having to hold off a few months to get the latest iPhone. We’re talking about missing meals, about deciding whether you keep the lights on or buy a few groceries. We’re talking, as Rick Bragg once put it, “about living and dying and that fragile, shivering place in between.” That’s pay dirt for a writer. And coming out of a storytelling tradition like the South for me, or Puerto Rico for you, I think puts us at a tremendous advantage. I can’t imagine growing up in a place where story didn’t matter. What a horrible, horrible life that would’ve been.

GI: Your career took off pretty quickly. This makes newbie authors look up to you and ask for help, tips, blurbs, and probably a connection. How do you deal with this?

DJ: I’ve been incredibly fortunate both for the success and for the support from fellow writers. The hard truth is that there are plenty of writers a lot more talented than I am who haven’t gotten their shot, and quite possibly never will. I have no idea what makes certain books take off. There’s really no rhyme or reason to what makes a bestseller. Part of it is timing, sure, but then I think about a book like Megan Abbott’s You Will Know Me last summer. Flat out that was one of the top two or three novels that came out last year. It was that good. Period. Even more it was about a gymnastics family and it released a week before the Rio 2016 Summer Games Olympics. Talk about timing. By all reason that book should have been in the top five NYT Bestsellers. Who the hell knows why it wasn’t? And that’s not to say that book wasn’t well received, because it definitely was, and rightly so, but I have no idea why some books take off and others don’t.

As far as other writers, I’ll never forget what it was like when that first novel was coming out and I got a blurb from Daniel Woodrell. I mean I idolize him. To think that he read my work still boggles me, and he didn’t have a reason in the world to do it aside from kindness. Another one is Ace Atkins. I think he’s one of the most talented writers I know. I respect the hell out of him on the page, but even more so as a man. He could call me right this second and ask anything of me and I’d be there. I owe him that much. I feel that way about Ron Rash, Tawni O’Dell, Frank Bill, Mark Powell, Michael Farris Smith, Silas House, George Singleton, Megan Abbott, Donald Ray Pollock, Eric Rickstad, Reed Farrell Coleman who are all a hell of a lot more talented than me and were kind enough to read my work and support what I was doing. I know what it’s like to not have an audience, to not have any work out there on the shelf, and I’ll never lose sight of everyone who supported me. I carry that with me and I carry that forward. Bottom line is that if I can help someone I help them because that’s the way this thing works.

At the same time, it’s rare anymore for me to go a day without someone I’ve never met asking me to read something. There are nine books sitting beside me on my desk right now that people sent me to read. So the truth is there comes a time when you have to say no and I think that’s a hard balance to find. I think it’s hard for most writers to say no, because most all the ones I know and love and respect are first and foremost damn good people when you get to the heart of it.

GI: Fishing is at the center of your life now. Every fisherman in the world has a different answer for this, and I’m curious about yours: what is it about fishing that keeps you going back for more?

DJ: Maybe the most beautiful passage I’ve ever read on fishing came from Alex Taylor and I can’t remember if it was in one of his stories or from his novel, The Marble Orchard, but he wrote, “There was now in him the desire to wrangle one thing out of the dark waters and have it leap and fight and finally be subdued by his hand. Because there is a kind of faith with fishing. It is the belief that the brevity of all things is not bitter, but a calm moment beside calm water is enough to still the breaking of all hearts everywhere.”

I think it’s exactly that and it’s always been that even when I was a kid. It’s chasing the same thing that Buddhists are chasing through meditation, it’s that moment of absolute thoughtlessness when everything else disappears and all that is left is the present. For me, I have a hard time reaching that place any other way so I’ve devoted a great deal of my life to being next to water. That’s the only place where I feel at ease. Fishing has always been my center.

GI: There is no fiction like that found in the “true” stories told by fishermen. What’s the most outstanding/memorable/incredible fishing tale you’ve heard?

When I was a little kid I used to always get up early on Saturday mornings and watch all the fishing shows—Roland Martin, Hank Parker, Bill Dance, The Spanish Fly with Jose Wejebe, Walker’s Cay Chronicle with Flip Pallot—but I remember one time when I was really little seeing this documentary on PBS about a noodling tournament in Oklahoma. It was the first time I’d ever seen anyone grappling catfish. People in my family jug fished and ran trotlines, and I’d caught plenty of catfish on rod and reel, but I’d never seen anything like that. I remember this one fellow on there saying you never knew exactly what might be in the back of one of those holes. Might be a catfish. Might be a snapping turtle. Might be a snake. He told how his brother stuck his arm in a hole once and a beaver got ahold of him and gnawed his forearm down to the bone clean up to his elbow.

Anyhow, there was a father and son fishing together and the boy might’ve been seven or eight years old, but they waded up to a hole and the father stuck his arm back in there and felt fish. The problem was that the hole was too deep and he couldn’t get back far enough for the fish to latch on. So this man took his son and shoved him down in that hole feet first and all of a sudden that boy got to screaming and hollering and the man dragged him out and that catfish was latched onto that boy’s legs. I’ve never seen anything like it. Here’s this father shoving his little boy down in a hole for a thirty, forty pound flathead to bite down on his legs. I just laid there in awe watching it, and I’ve never been able to shake that image in all the years since. Long story short, think long and hard before you go getting in a fistfight with an Okie.

GI: Your work is character driven, but there’s also a lot of attention paid to the beauty of each sentence, the cadence of each passage. How much of that comes out naturally and how much is editing/rewriting?

I think the ear for it comes naturally, at least for me. I hear a good sentence in the same way Thelonious Monk heard rhythm, or Dave Brubeck heard scales. Now I’m absolutely tone deaf when it comes to music, but I have a natural ear for language. Ron Rash talked one time about loving the way vowels and consonants rub up against one another. In the same way, I think I’m drawn to sound more than anything else, and that’s probably why I read so much more poetry than fiction. As far as writing it though, I don’t think that comes naturally at all. That’s very much a matter of shifting phrases, changing words, cutting articles, playing with things and tinkering with a sentence until there’s music. It takes a lot more work for me to construct a sentence than it does for me to recognize when one is working.

GI: Appalachian noir. Rural noir. Country noir. You fall into all of them and yet your work is clearly David Joy noir. Do you pay any attention to labels?

There’s a danger to labels that I think has led writers like Daniel Woodrell to distance himself from terms like “noir.” For too long merit has been measured by wine sniffing, elbow patch wearing, shiny shoed academics who turn their noses up to any label other than “literary.” Anyone with half a brain can recognize it’s snobbish bullshit. To dismiss someone like Ursula K. Le Guin under the guise of science fiction, or to dismiss a writer like Stephen King as a genre writer, that’s the danger of labels. Benjamin Percy had that great collection of essays last year titled Thrill Me where he did a wonderful service in addressing a lot of these issues. I think we’re starting to move away from that trend, and that’s a wonderful thing. I was on a panel with Megan Abbott in France last fall and she said she believed crime fiction had become the new social novel and I completely agree with her. So I guess what I’m saying is that as readers we need to be sure that we’re not carrying any sort of bias in regards to those labels. The book must stand alone.

At the same time, I’m not one to shy away from labels. I think my sentences stand for themselves and so if someone wants to talk craft we can talk craft. I like the idea of noir, especially as an emotional description capturing a sort of shadowed mood cast over a story. Benjamin Whitmer had a great essay a while back where he talked about the idea of redeemable characters and happy endings being a fairly new construct in regards to literature. Hollywood endings always hit me as such a cop out. So when a term like noir is used correctly I’m really grateful as a reader because it tends to point me in the direction of something I’ll probably dig. I also recognize that my work isn’t for everyone. I want to go to the darkest places imaginable and search out some small speck of humanity. I think it takes a brave reader to go to the places I want to take them. I hope there’s a payoff for venturing into the dark, and, for me, I believe that there is. Only through heartache and suffering do we arrive at any sort of philosophical awareness, and, in the end, that sort of revelatory moment is what makes it worthwhile.

GI: There’s a lot of misunderstanding when it comes to Appalachia, and part of that can be blamed on books that take place there and don’t understand the place, the people, the culture. Now that everyone writes about everything and everywhere, do you think authenticity still matters?

DJ: When I think of the truly great books, the truly great writers, I can’t think of one who wasn’t deeply rooted to place. James Joyce traveled all over Europe. He wrote Ulysses and Finnegan’s Wake while living in Paris. But could you imagine him having not written of Dublin? You know, he said, “I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world.” Joyce’s idea that, “In the particular is contained the universal,” is exactly what Eudora Welty meant when she said, “One place understood helps us understand all places better.” I don’t want to live in a world where Faulkner didn’t stick to Mississippi. I don’t want to live in a world where Ron didn’t write of Appalachia. Those books are sopping wet with place. I think there is an incredible beauty in knowing a setting as deeply as those writers knew theirs. I think you can sense that connection on the page just as I think you can sense when someone’s bullshitting. There’s nothing worse than reading a book and having the language ring untrue. As soon as I hit that place in a book, I’m done. I’m not reading any further. Toss it to the fire. It’s kindling.

If the details aren’t right the reader will never buy the big lie. So whether the writer’s of that place or not, it goddamn better feel authentic.

GI: Your Twitter feed is a great place to find great authors other than yourself. Any names/books you’d care to recommend here?

I think it’s rare for me to find a book that I absolutely love, especially a novel. So I wind up rereading a lot more books than I do finishing something new. I go back and read Jim Harrison and Larry Brown and Cormac McCarthy. Recently I reread Benjamin Whitmer’s Cry Father. I’m obsessed with Daniel Woodrell and Donald Ray Pollock. As far as novels I’ve read this year that I loved, I really enjoyed stumbling onto your work. Zero Saints is a wonderful read. I think the best novels to come out this year were Michael Farris Smith’s Desperation Road, Steph Post’s Lightwood, and Mark Powell’s Small Treasons. Frank Bill’s got a new one titled The Savage that’s coming out this fall and it’s brilliant. I think the best story collection I’ve read this year was Scott Gould’s Strangers To Temptation. I thought that book was wonderful, kind of like if George Singleton had written a season of the Wonder Years. I think more people need to be reading Robert Gipe, Crystal Wilkinson, Charles Dodd White, and Sheldon Lee Compton.

But I’m going to do this a little differently than most novelists and name five or six books of poetry I’ve fallen in love with this year. One of my favorite poets, Tim Peeler, has a new book out titled L2, which is a sort of linear, novel-esque story told through poetry and I loved that book. Gritty as hell and just damn beautiful. Another one of my favorite poets, Rebecca Gayle Howell, has a new book, American Purgatory, that’s incredible. I think she’s one of the most powerful poets at work. If you haven’t read her already, read her collection Render: An Apocalypse and you’ll fall in love. Recently, I read a beautiful book by a South Carolina poet named Kathleen Nalley. The title is Gutterflower and it comes out some time in September, I think, but her work has really stuck with me. I stumbled onto a poet named Adrian Matejka and read a book of his, The Big Smoke, which was sort of the story of the boxer Jack Johnson. A wonderful press, Hub City, put out a book by Ashley M. Jones’ titled Magic City Gospel, and there’s a poem in there titled “Sammy Davis Jr. Sings To Mike Brown, Jr.” that will wreck your world in fourteen lines. Lastly, I finally got my hands on Ray McManus’ Red Dirt Jesus. I’ve always loved his poetry, especially the poems in his book Punch, but Red Dirt Jesus was one of those books I found at the right time. I was finishing my next novel, a book that’ll come out next year called The Line That Held Us, and I read a poem of his called “Missing Curfew” and as soon as I read it I knew the final image of the novel, I knew how I wanted the last words to sound. I have Ray to thank for that.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)