La Casita Grande, 2017

REVIEWED BY GABINO IGLESIAS

–

Steeped in anger, misdirection, discontent, sex, alcohol, and the feeling of uncontrollable exasperation that is usually tied to states of agitated stagnation and solitude, Fernando Sdrigotti’s Dysfunctional Males is a hilarious, dark, and unapologetic deconstruction of masculinity that offers a raw look at the way the male psyche and its obsessions react to the harshness of life in a great metropolis. The collection brings together five stories that share a few cohesive elements: all take place in London, have a male protagonist, and dance between humor and despair.

The collection kicks off with “The Grid (Bosnian Charlie),” a tale in which a man goes out and spends the night getting drunk, dealing with the father of his friend who’s in town for a wedding that’s not happening, and snorting cocaine in an attempt to achieve “the grid,” a state of connectedness to everything that makes him feel superior and in control. As the night progresses, the drinks and coke mix with the man’s frustration and eventually coalesce into a monster made up of anxiety, anger, desire, and the need to stay in the grid. Unfortunately, despite the quest for depth and significance, the main character spirals into a gloomy, strange state of mind in which he ends up becoming another victim of the night with a mouth full of blood and shattered teeth. Before that happens, however, Sdrigotti manages to set the mood for the rest of the collection and to clearly show what some of his recurring themes will be as well as displaying his knack for detail:

I wash my face. Refresh my mind with the sound of a subbuffer vibrating a couple of rooms away. This tacky wallpaper and tacky lights. A dripping urinal and a flashing light-bulb. I look at my face in the mirror. Blue eyes, short blond receding hair, thin nose and pronounced chin, a piercing stare in my eyes: Steve McQueen, I have turned into Steve McQueen. It must have been the charlie or Babo Kanic’s influence. If you want to be a man you’ve got to hang around with men and do manly things. It’s so clear now. So evident. I wonder how it escaped me for so long. Or maybe I just forgot it.

“Elision,” the second story, is also a standout. The narrative explores the way a man fills in the space in his mind where the memories of the previous night should be. Not remembering quickly becomes a serious problem, and he eventually starts obsessing about the possibility of having been raped by another man. The narrative allows Sdrigotti to deconstruct masculinity in various contexts and to explore sexuality in interesting ways. This story is also one in which the author’s prose shines. Sdrigotti’s style, which resides in the interstitial space between literary fiction, surrealism, and gritty realism, is in full display here: memories are created and destroyed, possibilities are analyzed, and, perhaps most importantly, the fourth wall is bombed from the inside and Sdrigotti comes out screaming, somewhat like a literary version of the Kool-Aid Man:

It is a well-known fact that only mediocre writers make use of the oneiric recourse. Dreams in fiction are hardly ever necessary for the flow of the narrative; and more often than not are used as an artifice to increase the page-count of a certain work, in order to satisfy a publisher. What’s the point in talking about the dreams of a character? How can the imaginary activities of an imaginary character mean something to a story that takes place mostly in the mind of the writer? I for one have fell into this sin before. The day I decided to become a serious writer — that is the day I made my mind up that I needed to be approved of by peers, academics, and assorted cognoscenti — I dropped it and assumed a Brechtian approach to writing instead: a decent and sincere rapport with my reader, where I’m always aware and making him or her aware that what is being read on the page is fiction. So, at some point in my career my characters stopped dreaming and Adrian is not an exception. What happened between the time when he went to sleep and the time when he woke up — around two-thirty in the afternoon — could be said to be another elision.

The third story, “The Vanishing Onanist of E5,” also merits attention. In this case, for two very different reasons. The first is that this entertaining tale of a man spending his day smoking, thinking, and masturbating has the best, most surreal ending of the collection. Sdrigotti flexed some muscles in this one that he doesn’t engage in any of the other tales presented in Dysfunctional Males. There are some funny moments and some that delve into depression and loneliness deeper than most contemporary short fiction, and that makes this one a disquieting read that sticks with the reader long after the last page is turned. The second reason is not so positive. The wealth of details presented here walks the fine line between commendable and too much. The story is very effective, but the cumulative effect reaches its zenith here, and that hurts the two stories that follow it. “The Vanishing Onanist of E5” closes with a bang and “Satori in Hainault” starts, and the transition hurts the second story, which is also packed to the gills with pornography and explorations of loneliness, both of which are approached with a staggering amount of minutiae that includes enough scatological details to satisfy fans of hardcore horror. By the time the last story, “Herne Hill,” rolls around, the names of streets, descriptions, and confusion are all too familiar. More of what has already been offered happens: descriptions of public transportation, more passages inside the main character’s head, more details about spaces, and more conversations that lead nowhere add up to a tale that, on top of the preceding ones, is a tad lackluster. Perhaps this points to the only drawback of this collection: five tales that come in at over 240 pages means that this is more of a novelette collection that, given its recurrent themes, maybe should have ended with “Satori in Hainault.”

Dysfunctional Males is a great collection from an author who is a sharp observer and fearless explorer. It is also a book that should help put La Casita Grande on the map because of its strength and genre-bending nature.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

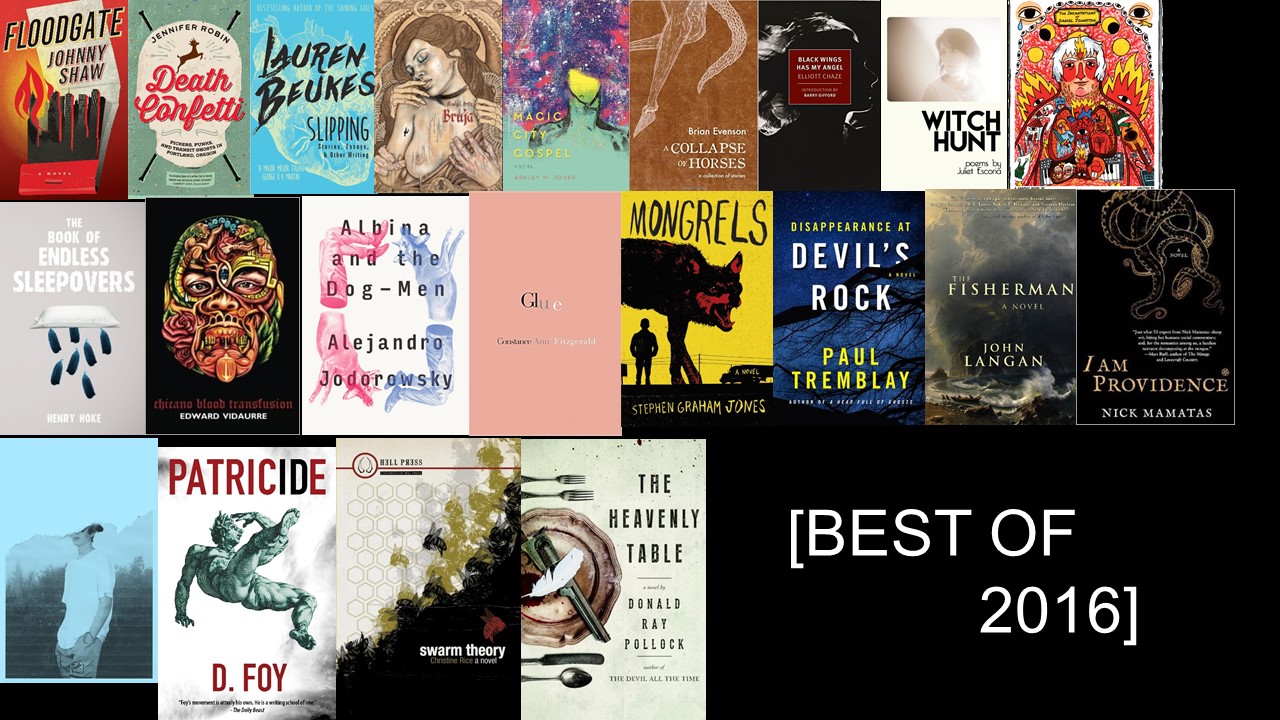

18. Bruja by Wendy C. Ortiz. What Ortiz does for the memoir here is comparable to what Flaubert’s Madam Bovary did for modern realist narration or what Capote’s In Cold Blood did for the nonfiction novel. Simply put, Ortiz’s “dreamoir” is a new thing and this book will be the starting point for a movement as well as the go-text for all upcoming memoirs that inhabit the interstitial space between reality, memory, very personal surrealism, and dreams.

18. Bruja by Wendy C. Ortiz. What Ortiz does for the memoir here is comparable to what Flaubert’s Madam Bovary did for modern realist narration or what Capote’s In Cold Blood did for the nonfiction novel. Simply put, Ortiz’s “dreamoir” is a new thing and this book will be the starting point for a movement as well as the go-text for all upcoming memoirs that inhabit the interstitial space between reality, memory, very personal surrealism, and dreams. 17. Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones. Going into a poetry collection without being familiar with the author’s work is always an adventure. With this book, the adventure yielded a treasure trove of southern imagery, a screaming celebration of roots and culture, and an unapologetically raw view of the female African American experience. This is brave, beautiful, necessary poetry that should be taught in schools and that undoubtedly becomes more important with each dumb step the country takes backwards.

17. Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones. Going into a poetry collection without being familiar with the author’s work is always an adventure. With this book, the adventure yielded a treasure trove of southern imagery, a screaming celebration of roots and culture, and an unapologetically raw view of the female African American experience. This is brave, beautiful, necessary poetry that should be taught in schools and that undoubtedly becomes more important with each dumb step the country takes backwards. 16. A Collapse of Horses by Brian Evenson. Evenson is one of the most talented living writers in the world, and this collection is full of stories in which he proves it time and time again. Sad, strange, creepy, touching, surreal, scary; if you can think it or feel it, Evenson does it here. The best short story collection of 2016 and yet another superb entry into the oeuvre of a man who seems to only get impossibly better with each new offering.

16. A Collapse of Horses by Brian Evenson. Evenson is one of the most talented living writers in the world, and this collection is full of stories in which he proves it time and time again. Sad, strange, creepy, touching, surreal, scary; if you can think it or feel it, Evenson does it here. The best short story collection of 2016 and yet another superb entry into the oeuvre of a man who seems to only get impossibly better with each new offering. 15. Black Wings Has My Angel by Elliott Haze. The folks at the New York Review of Books know how to pick their classics, and this one is my favorite so far. A narrative that still resonates in modern noir’s DNA, this is a dark, twisted tale of love, violence, secret agendas, and the way plans have a tendency to crumble.

15. Black Wings Has My Angel by Elliott Haze. The folks at the New York Review of Books know how to pick their classics, and this one is my favorite so far. A narrative that still resonates in modern noir’s DNA, this is a dark, twisted tale of love, violence, secret agendas, and the way plans have a tendency to crumble.

2. Swarm Theory by Christine Rice. I could write ten pages on the way Rice weaved together a narrative about a whole town and all its denizens, but that would probably bore you. Instead, I’ll say this: Swarm Theory is the most impressive book about a town/plethora of characters that I’ve read since devouring Camilo Jose Cela’s The Hive, and remember that Cela got a Nobel in Literature in 1989.

2. Swarm Theory by Christine Rice. I could write ten pages on the way Rice weaved together a narrative about a whole town and all its denizens, but that would probably bore you. Instead, I’ll say this: Swarm Theory is the most impressive book about a town/plethora of characters that I’ve read since devouring Camilo Jose Cela’s The Hive, and remember that Cela got a Nobel in Literature in 1989.