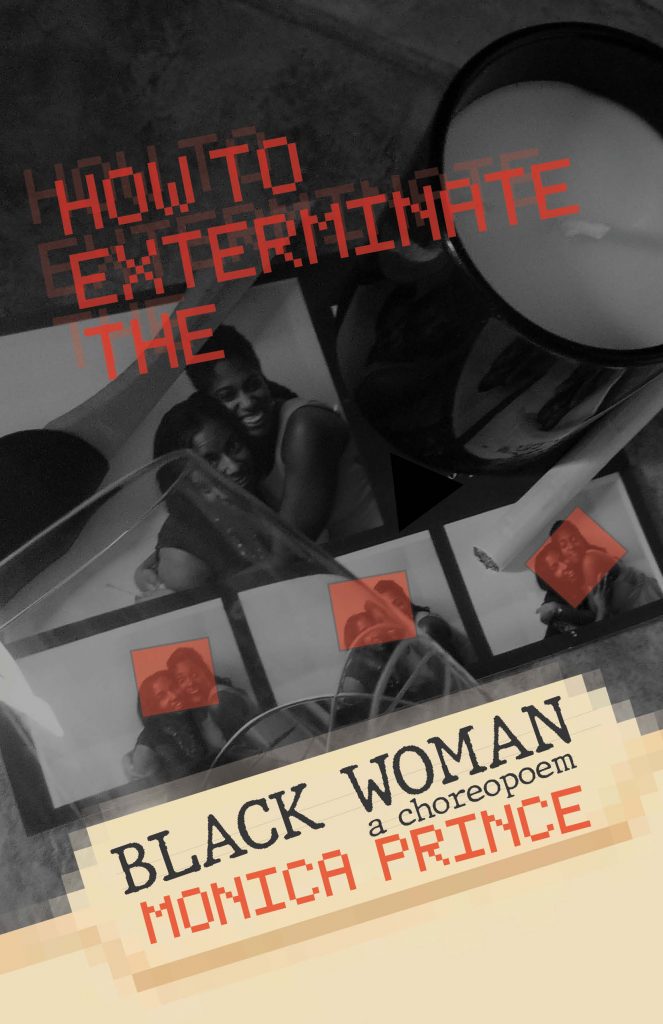

[PANK] Web Editor, Erinn Batykefer sat down with Monica Prince to talk about her new choreopoem, HOW TO EXTERMINATE THE BLACK WOMAN coming out from PANK Books, spring 2020.

—

For the readers who might not know what a choreopoem is, can you tell us about how you first learned about it and how you approach the form? What does it let you do that you can’t accomplish with another form?

In 2008, my sister called to tell me she’d just read the most incredible thing and I needed to stop what I was doing and go to the bookstore immediately and buy a book. “It’s called For colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf by Ntozake Shange. N-T-O-Z-A-K-E S-H-A-N-G-E. Now. Go right now.” It was like 10:00pm on a Monday, but I wrote down what she told me and the next day I went to two bookstores looking for it. (RIP Borders.)

For colored girls… is a choreopoem. That’s what Shange called it. This one was published in 1975 to critical acclaim. I read it in one sitting in my mother’s living room, out loud. I cried the whole time. It was the most amazing thing I’d ever read. I had been reading/watching/writing performance poetry for a few years at that point, and I was a dancer. This choreopoem combined performance poetry, dance, music, song, and art in a way I’d never seen, never dreamed was possible. I thought poetry had limits. I was wrong.

The official definition of a choreopoem, according to me and the thousands of sources I’ve read to become an expert on this genre, is a choreographed series of poems performed on stage with dance, music, live art, and occasionally parkour if you do it my way. The structure takes on at least three forms: a collage, a narrative, or a hybrid where the narrative isn’t the dominant structure but provides a thread to follow from beginning to end. For colored girls… is a collage choreopoem: several characters perform poems with various speakers, transitions are done through dialogue or dance, and they end where they started: “And this is for colored girls who have considered suicide but are moving to the ends of their own rainbows.” (That’s in the first poem and the last.) There are about twenty poems in that show.

My latest choreopoem Roadmap is a narrative choreopoem. There are characters who change, they only speak in their own essences, and the audience can follow the narrative through dialogue, a chorus, and a guide (her name is Rachel, and she’s terrifying). How to Exterminate the Black Woman is a hybrid of both the narrative and collage form.

Though I do write “literary” poetry, what I can accomplish with the choreopoem is a captive audience. People attend the show to see what all the hubbub is about. They want to know why it’s called that and not just a play. They want to know why people are singing or painting on stage or dancing or doing backflips. They want to be immersed in something they’ve never experienced before. They want to ask questions about people they don’t always engage with, lives they never interrogate, experiences they’ve never had. I can’t do that with a poem in a book. I can’t do that with just a play. I can’t do that with an essay (well, I can, but not as effectively).

Ntozake Shange passed away in October of 2018. She likely never knew about the work I’ve been doing, how I have done all this in her honor, for her legacy. I hope she’s proud of me.

HOW TO EXTERMINATE THE BLACK WOMAN functions a bit like a beehive, a single organism made of many. I’m thinking specifically of the sections that are also poems from other books and manuscripts. I’m curious about how you approach writing your choreopoems. Are they like writing a play? Ordering a manuscript and filling in? Something else?

So, writing a choreopoem is one of the most ridiculous things I’ve ever done, and I can’t stop doing it. How to Exterminate the Black Woman is my fourth choreopoem, but only the third to be produced, and the first to be published (yay!). I wish I could say it is the same every time, but it’s not.

My undergraduate honors thesis will tell you that writing a choreopoem requires choosing a subject, researching that subject through interviews and literature reviews, choosing characters, and then writing a million poems until you get “enough.” Which is why some of the poems come from other books and manuscripts. As I write poems, some of them are just fabulous on their own so I submit them to journals or they become part of other collections. But sometimes, as I pull poems together based on the subject, I end up pulling from sources that have already been published. To be honest, I never believed choreopoems could be published as literary works. They are frequently published as plays (Samuel French, for example, owns the rights to For colored girls…) or self-published on Amazon or produced and never repeated (like the 1982 For black boys who have considered homicide when the streets are too much by Keith Antar Manson). But really, the choreography of creating a choreopoem is different every time.

When I started How to Exterminate the Black Woman, six words came to me in a dream that my dog startled me awake from in the middle of the night (RIP Otis the Pug). I wrote a feverish sestina using those words: fear, expectation, fury, loss, silence, and new. Then I went back to sleep. In the morning, I reread the sestina (titled “When Asked About Power, I’ll Tell Them–“), changed some stuff, and then wrote an outline for the show. I had no plan. But I knew I wanted the show to respond to Beyoncé’s Lemonade (specifically in “Freedom” when she says, “I’mma keep runnin’ cuz a winner don’t quit on themselves”) and I wanted to give a tribute to my closest friends from college, five women who kept me sane my last two years at Knox. But most importantly: it was the summer of 2016. I didn’t know what was going to happen with the election. I was in love with a Black man who I couldn’t keep safe. I was teaching Black children in a summer literacy camp, and Philando Castille and Alton Sterling had just been murdered. I looked around and I couldn’t breathe. I just kept writing poems about Black lives being disposable, about the tragedy of loving someone “who will leave, be taken from you”, about fiercely and unapologetically identifying as a Black woman.

Then one of my best friends from college got pregnant.

We’ve handled this so it’s okay to talk about. I was the first person to ask her if she wanted to keep the baby. I asked if this was what she really wanted, with her partner (of ten years at the time), with her life. I tell my students all the time that any decision you make you can unmake. Except having a whole child. That decision cannot be unmade as cleanly as moving to the wrong city or taking the wrong job. Humans have consequences. Surprise surprise we fought about it. But the reason I asked was because DT was dangerously about to become President. Black bodies were dropping like flies and no one seemed to care or want to do anything about it.

How do you raise a child in a country that wants to kill them, that wants to kill you?

After that, the show came easily. I had a focus. I had a direction. I knew I wanted the show to answer that question. I was (still am) obsessed with sestinas, so I wrote like twelve more with different subjects, and the whole show was focused around the number 6. Did you know 6 is a perfect number? In the show, there are 6 sestinas and 18 poems, 6 main characters/emotions, and each of them recites at least two sestinas. The moment the show stopped being a collage and turned into a hybrid was when I realized that the show was all about my insecurities about growing up: society tells you to have a baby, to get married, to buy a house and get a steady job and retire at 65 with grandchildren to spoil. But I’m polyamorous, terrified of getting pregnant, and wildly uncomfortable sharing my personal space. How am I supposed to be the person society wants me to be when I defy those norms by “bein alive and bein a woman and bein colored” (that’s Ntozake Shange right there)?

The narrative began when I introduced Angela and made the six emotions/characters fractured identities she holds. (Angela is my mother’s middle name, and it has six letters, and it means “messenger of God,” which is who Angela strives to be by the end of the show.) Then the show just asked for cohesion, for breath and grace. Using 6 as a guide, it fell together easily.

You’ve had the chance to see HOW TO EXTERMINATE THE BLACK WOMAN performed on stage, and to direct it, too. If you could hand-pick a dream cast, for the “parts of a Black woman” who would you put in each role?

Dream cast? Oh wow. I have never thought about that! I love this question.

Angela: Janelle James. I know she’s a comedian, but her energy is so on point for a character like Angela.

Fear: Lupita Nyong’o. I think she’s could do the “Closed Borders” poem justice, which has been difficult to get someone to do. Not to mention she has the talent to handle a character that experiences depression the way Black girls are “supposed” to experience it (read: we’re not supposed to get depressed).

Loss: Kimberly Elise. If you’ve seen the For Colored Girls movie, you know WHY.

Expectation: My best friend Kristyn Bridges. I wrote this part for her.

Silence: Mandi Madsen. She is this stellar actress in NY who is also one of my sister’s best friends. She has RANGE.

Fury: Kerry Washington. I watch Scandal when I run on the treadmill because nothing gets you fired up like watching Olivia Pope handle anything. Plus, have you seen Kerry Washington scream? It’s haunting.

New: Liz Morgan. She was “Binette” in my choreopoem Testify produced by the CutOut Theatre (directed by Thea Wigglesworth) in 2015, and she astounded me. If I could be in her light one more time or get her perform in one of my shows again, I would cry uncontrollably.

This book is comprised of sestinas, a form that functions on subtle and nuanced obsession as it repeats 6 line endings throughout. Are forms your jam, or was the sestina the right vessel for this choreopoem?

Sestina had to be this choreopoem’s vessel. I do not ask the muses questions when they give me gifts, and when they gave me the six characters for the show, I knew the sestina was the best way to format the show. I love forms, but I only developed a real respect for them last semester when I taught Forms of Poetry. There aren’t a lot of forms developed by writers of color, or at least we like to think so, and I appreciated how the sestina challenged me to tell a story cyclically. I can say Black bodies are disposable in a different form or a free verse piece, but the sestina requires you hear it over and over again in new ways, forcing you to really pay attention.

If you could ask a reader to do a little homework before reading your new book, what would your reading list look like?

Ooo! Homework? Yes. Not all of these are books, but choreopoems aren’t really books either, are they?

For colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf by Ntozake Shange (choreopoem)

Made to Dance in Burning Buildings by Ayva Pearson (choreopoem)

Let Me Down Easy by Anna Deavere Smith (one-woman show)

Love Poems by Nikki Giovanni (poetry collection)

Native Guard by Natasha Trethewey (poetry collection)

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates (memoir)

Dream with a Glass Chamber by Aricka Foreman (poetry chapbook)

Ferrous Wheel by Natalie Sharp (poetry chapbook)

The Dozen by Casey Rocheteau (poetry collection)

We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie (speech/nonfiction essay)

Lemonade by Beyonce (visual album)

Warshan Shire (poet featured in Lemonade)

Ebony Stewart (performance poet)

Citizen by Claudia Rankine (poetry collection/essay collection)

“won’t you celebrate with me” by Lucille Clifton (poem, but also read everything by Lucille Clifton)

I read/watched/experienced all these texts and people leading up to completing my choreopoem. There are way more, but these are the ones that pop up the heaviest for me.

Color is important in this text. There are 6 voices or “parts of a black woman” that come alive on the page / stage & each is associated with a color– a literal scarf that an actor wears. Is this a nod to Ntozake Shange?

This is partially a nod to Shange. I’ve become obsessed with ancestry and legacy. I don’t mean family trees; I mean artist ancestors, people who pass down their gifts to us so we may use them in a new life. Shange’s For colored girls… uses color directly: her characters are named lady in blue, lady in orange, lady in purple, etc. My characters use color to nod to her, but also because the spell at the end of the show doesn’t work without the right colors.

In 2017, right before I officially finished the show and started submitting it to playhouses and festivals, I met a witch named Ellen Ercolini at Practical Magic Live, a live event I host with Makenna Held and Andréa Renée Johnson (now called Your Leadership Recipe, come see us in France in April!). Ellen told me about frequencies, and when she read mine she looked me deep in the eyes and said, “So much water. You need time, space, and money to write, or you will never be happy.” That was terrifying since I was working five jobs and was definitely not writing. She also told me blue (royal blue, specifically) was my power color and if I wanted to channel energy into something, I needed to use that color. Twenty-four hours later, my best friend Kristyn gave birth to her son, Royal.

I believe in witches. I believe in muses and spirits and angels and energies and frequencies and miracles and God. I do not believe in coincidences (Rule 39, if you watch NCIS). But I do believe that when a witch tells you something, you have to believe it.

I wrote a spell as the penultimate poem of the show, “Battle Stations.” The colors came from that spell. Before, the characters/emotions were just named. I knew if I wanted something powerful to happen, if I wanted Angela to cease being fractured and return to herself, the spell had to have not only my power color, but the power colors of the women who saved my life in college: purple, silver, yellow, red, green, and of course, blue. Angela wears a black scarf at the end because when you mix all the power colors together, you get black. Get it? Like the Black woman fractured at the beginning of the show?

Anything else you’d like to share with [PANK] about this exciting new title? [PANK] loves you!

How to Exterminate the Black Woman is not just about the struggle to remain whole in a world that blatantly wants to erase you. It’s not just about the collective memory of Black women navigating relationships with themselves and others. It’s about legacy, about how no matter how often white supremacy, misogynoir, fire, nooses, and bullets try to exterminate us, they have failed. They have failed. They will fail. Every other choreopoem I’ve written was based on interviews and research. This is the first show based entirely around surviving where you will never belong.

If you want to perform the show, get at [PANK]! They would love to send you copies and a rights agreement!

—

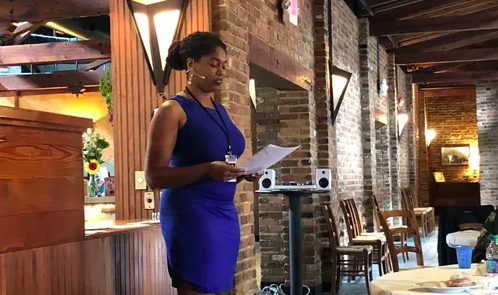

MONICA PRINCE, a Black performance poet raised by Guyanese parents, teaches activist and performance writing at Susquehanna University in central Pennsylvania, where she writes choreopoems and performance poetry. Her debut poetry collection, Instructions for Temporary Survival (2019), won the Discovery Award for an outstanding first collection by the publisher, Red Mountain Press. She is the managing editor of the Santa Fe Writers Project Quarterly and the author of the chapbook Letters from the Other Woman (Grey Book Press, 2018). Her creative work is featured in MadCap Review, The Texas Review, TRACK//FOUR, and elsewhere.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)