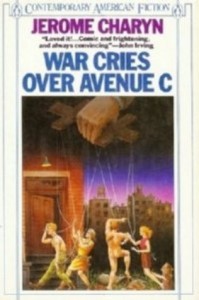

Originally Published by Donald Fine, 1985

Review by Morris Collins

In his biography of Isaac Babel, Jerome Charyn describes discovering Babel’s writing for the first time. “I read on and on. I found myself going back to the same stories—as if narratives were musical compositions that one could never tire of. Repetition increased their value. With each dip into Babel I discovered and rediscovered reading itself.” This description perfectly reflects my experience of encountering Charyn’s own mysterious novel, War Cries Over Avenue C. Reading it for the first time was an epiphanic experience: I had just finished college and decided that I was going to be a writer. This meant that I was taking a year off, doing manual labor, and writing everything I could: stories, novel fragments, poems. I had an inkling that I was decent with language but unschooled in form. I wanted to learn the rules—how did a story work? What was a novel supposed to do? Then I picked up Charyn’s novel—and found myself quickly beyond any literary world I recognized, beyond the terra firma of conventional plotting, form, or genre. It was a novel of linguistic bravado, narrative mayhem, and structural acrobatics—a beautiful and crazy book where the author never stopped to wink or nod at the reader. Unlike in Pynchon or Barthelme—two writers Charyn is often compared to—the absurdity felt desperate, essential, and real. You could tell Charyn believed absolutely in his vision.

War Cries Over Avenue C opens as a war novel, a chronicle of two lovers who separate and find each other again on the front lines of the Vietnam War, but from this fairly traditional point it explodes out in a lyric howl, a novel of war and espionage and love and drugs that reads like a chronicle from the dream side of the twentieth century. Here, from early in the novel is Uncle Albert, a Henry James scholar and American spymaster discussing the war: “It’s a clump of ideas too far out for the regular boys…We conduct a war that runs counter to the war that’s going on…We don’t stop at any border…We go anywhere to get what we want.” Ostensibly he is describing the CIA’s covert operations along the Cambodian border, but he could just as well be describing Charyn’s novel itself, a novel running parallel to, but perpetually separate from, conventional popular fiction, too far out in every direction, alive with language that, as Charyn describes Babel’s prose, “reverberates in every direction.” Continue reading

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)