BY JONATHAN MARCANTONI

—

It was in the 90s when I began writing, first on a cheap computer program my dad bought me that mixed cut out animation with text. At that time, living in the Deep South, I had no knowledge of academic studies on ethnic literature or Nuyorican politics. We were Puerto Ricans and very simply so. Racism was apparent, and came from both the Mexicans who looked down on Puerto Ricans for no other reason than tribalism, and whites who were just ignorant and didn’t know what to do with a kid who was not light enough to be white, not tan enough to be immediately labelled a Mexican, and not dark enough to be black. So, I fell in with the black kids, and black art, and I was emboldened by the bravery of black artists to not only let their voice be heard but to be proud of their skin, their culture, and their unity as a people. The self-hatred and victimization of the Latino community was not something I was aware of as a teenager. I didn’t know I shouldn’t be proud of being Puerto Rican the same way James Brown was proud to be black. Becoming a writer broke down that ignorance, most often in conversations with the gatekeepers and mentors I relied on.

At age 15, applying for a writing program at a state arts academy:

Jon, you have such a great voice as a writer, why do you focus on such negative subjects?

How is it negative? It is real life.

Well, it’s just that…you’re just a teenager, why do you want to write about social problems?

Would you say that to Steinbeck?

Jon, there is no reason to compare yourself to famous people, that really gets you nowhere.

But why can famous authors write about social problems and I can’t?

(pause)

I think…this might just be too dark for an application to a state school. Most young people write science fiction or fantasy, maybe romance, but a union strike? They might not be the best audience for a political piece.

The guidelines don’t say what I can write about, just the length and that we can’t use profanity.

Right…well, I can’t stop you from submitting this. But in the future, I think you really ought to consider your audience.

At age 20, giving a writer friend who had been published a story of mine for feedback:

Jon, this is a really great story, but have you thought about setting it in the US? Most people in publishing don’t know much about Puerto Ricans if they don’t live in New York. And do they have to be Puerto Rican?

I am Puerto Rican, why would I not have my characters be as well?

I get that, I get that, but do they have to be Latino? It’s such a universal story—

So, the only humans capable of representing everyone are Americans, or let’s be honest, white Americans?

That…Jon, don’t get defensive, I’m just talking about your audience. You wrote this in English, and the people who would be reading this are not likely to be Latino.

I’m not going to be someone I’m not.

And I’m not asking you to be, I’m just saying you gotta play the game sometimes. Get published by following the rules and then you can experiment and have your stories be about whatever you want them to be about.

At age 22, talking to my aunt about the book I had just written:

Jon, you are such a good writer, and you have so much passion for our culture, I love it, really, but do you have to write about such dark things? Isn’t the world sad enough as it is, why can’t you write stories that are more positive about our people?

Well, tia, I want to raise awareness of issues that affect us and that need to be talked about.

I can understand that, but we have so much negativity about our people, why add to it?

So, I should ignore what goes on in our communities so we can feel better about ourselves?

That’s not what I’m saying—look, we have it really good compared to other people, and I think your writing would go a lot farther if you weren’t so critical of the United States too. I mean, you should be more grateful for what this country has done for you and our family.

At age 27, talking to a black screenwriter about my second book, which I wanted to adapt:

Jon, this is a great story, but have you ever heard of race-neutral storytelling? When producers look at a script, they base its marketability on how wide of an audience they can attract, and the more racially specific a story is, the less people will be interested. So instead of having Puerto Rican characters in Puerto Rico, why not move this story to Los Angeles and make the characters’ racial identity ambiguous, and maybe have a couple smaller characters be Mexican, it is LA so you can get away with that, but overall make it more universal, which is to say, neutral. And cut out the political commentary, just focus on the crime stuff and maybe find a place to add a romantic subplot, since that really appeals to people in the suburbs.

At age 27, receiving a review from a white blogger for the same book:

Jon, I gave this book a chance but couldn’t make it past the third page. Have you ever taken a writing class? Have you ever read a book? Chapter headings are centered three lines down a page as “Chapter 1, 2, 3” etc. and not any other way. You don’t go back and forth between narrative and thought without putting thoughts in italics and dialogue uses quotes, not em-dashes. Finally, mixing Spanish and English and not translating the Spanish really alienates readers and limits your audience. You do want people to read this, right?

At age 30, receiving a rejection letter from a major publisher for my third book:

This is a fascinating and vivid book that is intelligently written, however, we have a hard time seeing how it would be marketable for a wide audience since it lacks a relatable character.

It is at this point that the culture began to talk about micro-aggressions outside of the university. Concepts of intersectionality and modes of oppression became commonplace on talk and news shows, but for most of my life I had seen these things play out and understood, even at age 15, that what people didn’t “get” was why I would waste my time writing about brown and black people struggling for dignity and respect in their careers, their personal lives, from their government, their friends, and their family. Had they been white characters, probably no one would have batted an eye. Had the stories set in Puerto Rico or in Puerto Rican communities instead have been Irish or Italian or had the protagonist been a white observer who could give the white reader an “in”, my work probably could have received interest from a larger press, maybe even a Big 5 one, had I played the game of appealing to white sensibilities and assuaging white guilt by portraying my homeland as worse than even the gravest crime the U.S. had ever committed to us and that any good that came to us came from the U.S. Had I remembered to praise the American Dream and have my Latino characters yearn for nothing more than to be another thread in the great nation’s fabric. Had I been a house spic, they would have let me in. Stay in your lane. That is the between the lines refrain I decipher from this small sampling of conversations about my work. Stay in your lane.

Instead, I chose universality. My first book looks at people from all walks of life, educated and not, rich and poor, addicted and straight-laced, selfish and selfless, human beings who happen to be Latinos. My second was set in my homeland and dealt with politic corruption and human trafficking, but more pointedly, it was about the exploitation of the poor for the sins of the wealthy, showing how both Americans and those Puerto Ricans who support them, most often light skinned as well, get away with murder while the poor and black Puerto Ricans suffer for far lesser crimes. My third book was about club kids and mental illness and the desire to return to Puerto Rico to fully achieve our dreams. A subversion of the American Dream that has oppressed our people for ages. If we are to move forward as artists we have to tell stories that are universal, even while being specific to a particular experience and point of view. We have to think of methods of expression that are not so easily explained by ethnicity or country of origin. But to do so we need an outlet for such ideas and stories to flourish. If I was going to be a gatekeeper, then I had to supply the infrastructure, and so one more conversation had to occur.

At age 31, conversation between my ego (represented here as Suge Knight), and my id (represented here as Dr. Dre):

Suge: The fuck do you want?

Dre: I’m here to tell you I’m cutting my losses and setting out to start my own company.

Suge: And what are you expecting from me?

Dre: That you let me go. That your bullshit insecurities and shady past don’t interfere with my plans.

Suge: Boricua, why should I do that?

Dre: Because what I’m about to do will make you look good as well. You can even take credit for all you taught me these last few years. You see, I’m gonna provide a space, a lounge, for people of all races and backgrounds to contribute their work and get feedback and encouragement. A space where mentorship can be fostered and developed. And this space will be accompanied by a book publisher for Latinos and Caribbeans to tell stories outside the white gaze, outside the stereotyped expectations placed on us, stories of humanity that transcend genre and expectation. We will be that space for writers of color to truly be themselves.

Suge: How you gonna make money off some dumb ass shit like that?

Dre: It’s not about money, it’s about expression, and because we are filling a need, serving an underdeveloped market, we will attract attention, instead of dipping into the same waters as other new presses.

Suge (scoffing, rolling his eyes): Alright, you want to jump off a deep end and say fuck you to the white man I’m not gonna stop you, but I still think it’s stupid. So, whatchu gonna call that bullshit?

(Dramatic pause)

Dre: La Casita Grande Press.

(Cut to black)

—

Jonathan Marcantoni is a Boricua author of four books, and the forthcoming Tristiana. He is co-founder, with his wife Suset, of La Casita Grande Press.

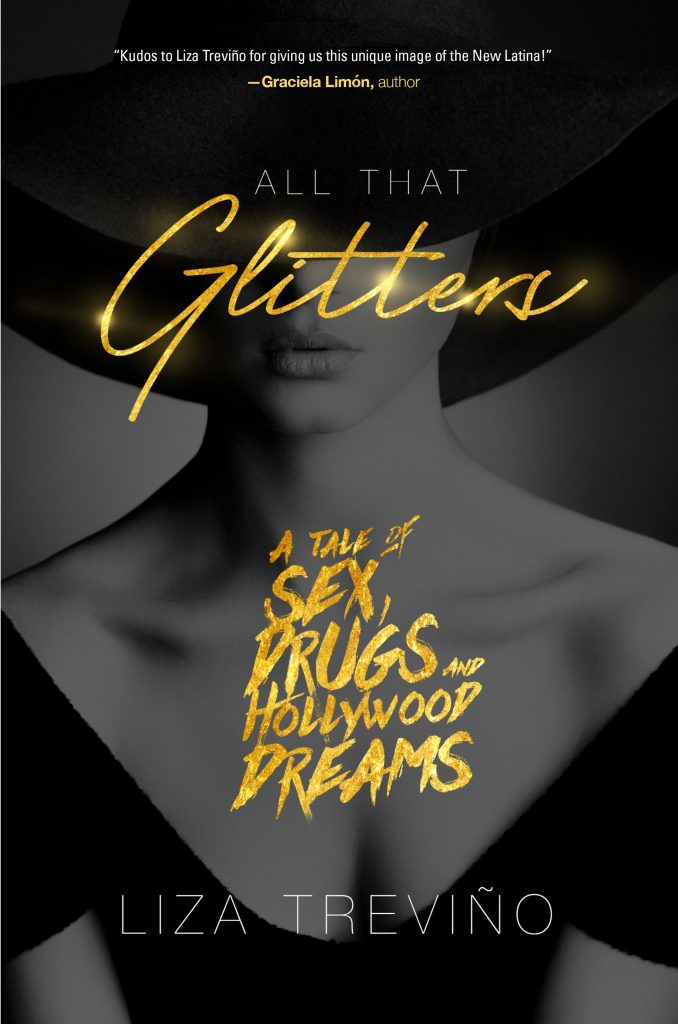

Koehler Books , 2017

Koehler Books , 2017![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)