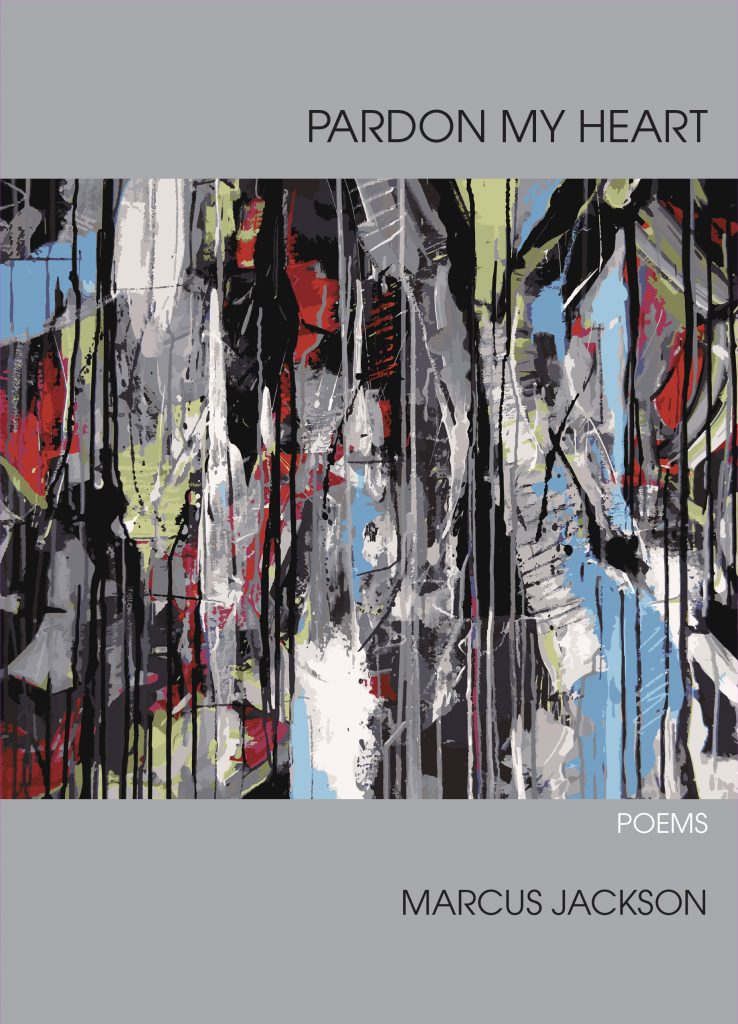

(TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern 2018)

REVIEW BY NATHAN ELIAS

—

In his sophomore collection of poems, Pardon My Heart, Marcus Jackson exposes his own heart while also putting an ear to the heartbeat of the contemporary African American ethos. The collection is broken into four parts and investigates not only how an individual’s heart can be amplified by “mistakes—long ago and recent” but how the American heart can take no shame in ruining a party after too much to drink, “doing its little two-step, aglow / in the middle of the room, never / happier to have nowhere else to go.” Judging by the scope of longing, regret, and adoration in this collection, it is evident that Jackson’s heart is a big one and full of ardor. The speaker in these poems provides testimony of a life lived, of a heart broken and self-mended while simultaneously demonstrating a hardness and unwillingness to be shaken by “love’s complex breaths” “full of beauty and absurdity.”

In Part One, Jackson reminisces on the sweet naiveté of youth—Friday nights at Paradise Skate (“We shimmied on small, oiled wheels, / until sweat glazed our faces, until motion / swept the debris from our beings”), old Regal or Fleetwood “amplifiers / with enough wattage / to shock polar bears” losing a fistfight and dissolving to Mary J. Blige on the radio. Meanwhile, Jackson laments over what to do with all his longing while wishing he could sing “as southern as Muddy, as electrically / as Jimi.” However, Jackson does sing throughout these poems. He sings to the love gods in thanks of “permission to mend, for prescribing time and somber songs / as balms”; he sings of the dominion of men, in which a tenth grader mournfully becomes a local legend for knocking out someone twice his age and weight, “an addict / who’d racked up enough petty wrongs / to earn a defeat from a skinny teen”; he sings of jail phones and bullet-shattered windshields.

In Part Two, Jackson travels back to the night of his birth in the Rust Belt, a fact he admits lying about and “saying I was born in a garden so near / the sea that my mother—multilingual / rinsed me at the fringe / of the tide.” While entering the realm of the unreliable narrator, Jackson is no less hesitant to deny such a baptism at the end of his poem “Evasive Me”; he calls out that he’s disinclined to allow “my ears and my mouth any songs not made / from the water, dirt, wind, salt, and fire / of American manipulation.” Jackson’s admiration for his mother continues throughout second part in poems like “Off Camera” in which a black-and-white photo of her reveals a young woman, before the poet’s birth who “sees / the brutal plentitudes waiting to break her.” This poem is effectively arranged after “Lullaby,” a retrospect on a baby after a bout of domestic violence. Here, Jackson asks, “Is there / a sure way to love a man the world won’t quit dealing trouble to?” The woes of a chain-smoking mother lineate in the poem “Ashtray”, the centerpiece of which being the object filled with the mother’s smolderings during her “lapses in labor or happiness.” Part Two moves on to trouble-making in the Rust Belt where characters steal triple beams from a school’s chemistry to make soda-cooked cocaine. As any reader of Jackson’s first collection, Neighborhood Register (CavanKerry Press 2011), will know, the Rust Belt’s streets and grit hold a special place in the poet’s heart. In poems from the first collection, such as “What the Baddest Kid in Our Neighborhood Said to Jasmin Jenkin” Jackson speaks as an authority on those who “keep a gun on [them] like ID” though they surely “don’t need it.”

In Part Three, Jackson turns toward the flesh, “so much…you’d like to touch / but don’t.” He admits to a love that made him “fine with dying” that his soul is so outlandish his body can barely hold it. Jackson reminds readers, though, of times “I’ve been getting along better / with my bartender than with my lover.” The early onset of love evolves through Part Three, away from the flesh and into separation, “an intricate, tireless silence.” Jackson paints an image of a newly adult couple fighting while the sky divides, and a time when his “bigmouthed heart” longed for the loneliness he lost.

Part Four finds the poet “in a kingdom of marvelous heartbreakers” including himself, his father, uncles, cousins, and wife, for whom he writes of buying a ring, despite “the wound [his] wallet had just become.” In an homage to his wife’s hips, Jackson draws parallels to hips that “share genes with the hips of American slaves” and also make “White women lower their heads / like children who’ve broken a dish.” The unflinching need to draw in those he loves is unyielding as Jackson writes on about his wife’s hair that sings “some kind of refrain / that does to the mind what / the mid-sky moon does to the night.” The collection finishes with Jackson confessing to listening to his wife’s breathing while she sleeps, her advanced asthma like “sand being scattered / by a wind the sea only brings / during darkness.”

Pardon My Heart cements a life of love within its pages, and though the cement ends up cracked, Jackson knows how to build a statue from the rubble.

—

Nathan Elias is the author of the novelette A Myriad of Roads That Lead to Here (August 2017) and the chapbook Glass City Blues: Poems (September 2018). He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University Los Angeles and has served as Fiction, Art, and Flash Fiction editor on the literary journal Lunch Ticket. He has taught a variety of creative writing classes, including fiction, poetry, and screenwriting. He is currently working on a novel.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)