WORDS BY BY M. SULLIVAN

—

There’s a woman unveiling a painting, on the right, by the entrance. She grips a red, tasseled cloth half-draped over the canvas. Poised like this, she is a matador. Her gaze is locked on the entrance. From looking at the whites of her eyes and how she holds herself, she is prepared, able. She conducts us into the gallery. And, like a bull, she tampers with our expectations. We expect conflict, but are fooled into a dance. We think we know, but are deceived. We are distracted by a fragment, while the whole picture remains obscured. The artists exhibiting at Aicon Gallery remind us that there is always more that remains to be seen.

Mequitta Ahuja, Material Support (Study III), 2017, Oil on canvas

Mequita Ahuja, the woman in the painting, is an African American with South Asian heritage. Her angular portraits feature cropped scenes and barren backgrounds, giving us incomplete narratives and brief glimpses into rich lives. Accompanying these intimate scenes, Ahuja’s Pomegranate Molasses (2018) and Sesame Paste (2018), present us with traditional Middle Eastern food—a nostalgic view of an area most readily associated with war. With only words and scattered snippets of facts about pomegranate and sesame, a small part of the region’s history buds into light. A recipe for sesame cookies conjures a bygone childhood and the sweet smells of a comforting home, tossing away prejudged visions of a strife-filled life.

At the rear of the gallery, the Indian artist, Rina Banerjee presents us with a work that invades and recaptures your eye at every chance. The work’s title is a brief story that begins with the stark line, She would be a vision of Beauty if only…her complexion was whitened! (2019). A bust of a woman rests on an ornate wooden stool. She has downcast eyes. Lines of cotton thread lead from the bust to the mirrors covering the wall behind her. Though she is turned away from her reflection, she is tied to it—it is inescapable. In each mirror: a fractured image. One angle shows the bust, another shows nothing, some strings, the viewer, the other works in the gallery. As the mirrors hold a prominent and imposing position in the space, the gallery, too, is flooded with the same inescapable vanity.

Along the west wall, in beautiful and horrific contradistinction to the former artists, are the works of Peju Alatise. Working with metal, stone, and resin, among other materials, Alatise has a hardness, a jaggedness, that keenly confronts the viewer. The eighteen panels collectively entitled Lost (2015) make use of a wide range of colors and patterns that gesture to traditional Nigerian textiles. The patterns at the tops of the panels taper off, fraying, as torn fabric, giving way to sawtoothed rips in the panels that resemble rusted iron. Within these holes, there are figurines with long and snaking limbs—all painted red like intestines. The violent gashes spill Nigeria’s innards—the country is wounded and vulnerable. Still, the bright colors of its culture overawe in their brilliance.

Peju Alatise, Lost, 2015, 18 mixed media panels

At the base of a spiral stair are three seated figures—Lagbaja, Tamedu ati Ogbeni (Anybody, Nobody, Somebody) I, II, III (2019). Each is cloaked in a tattered red cloth. Life-sized, their macabre presence is felt and not easily ignored, instilling fear in the space. The first bears a cross, the second carries an assault weapon, and the third wears an immense necklace of rosaries. The cross, the rifle, and the beads are composed of a number of small human statues. The figures of the cross scramble and clamber over one another as though in desperation; the figures of the rifle are supine and rigid; and the figures of the rosary beads are curled into fetal balls. As an attendant explained to me, Alatise, who is from Lagos, Nigeria, sadly could not come to the opening night because of a visa restriction. Looking once more at the seated figures, such a circumstance was dispiriting, yet unsurprising—as though by now we should be used to such barriers.

On the second floor, the works of two Pakistani artists form unexpected connections. The first artist, Faiza Butt, creates fantastical paintings and ceramics decorated with cartoonish line drawings, starscapes and toys, like childhood dreaming. One portrait, entitled Ghost (2019), stands apart. It shows a child wrapped in a blanket, calling to mind an image of a refugee. Planets and stars still fill in the background as with the seemingly more lighthearted works, but the child’s eyes are faraway, staring at some point just below the viewer’s gaze, and so looking through the viewer, as though we are the ghost.

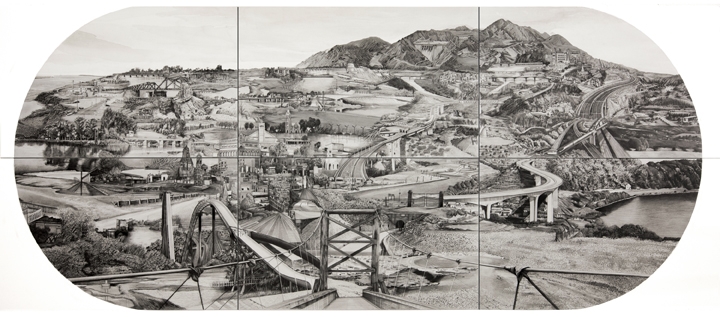

Positioned next to these large, colorful and dreamlike works are the small, graphite drawings of Saba Qizilbash. Two of Qizilbash’s larger drawings, Sialkot to Jammu (2018) and The Grand Trunk Road – Kabul to Torkham (2019) depict cities on the India-Pakistan border and the roads that connect them. Drawn on a series of panels, the hard lines separating one section of the scene from the next give the image a vaguely surreal quality as pieces that certainly align nevertheless seem off at the same time, as though the border between them distorts the whole. Butt’s and Qizilbash’s widely different works, displayed side-by-side, bridge the line between a sharp reality and a magical otherworld. We are left to wonder about their relation—if they are perhaps different tellings of the same story or if, together, they somehow form a more complete tale of the artists’ shared homeland.

Saba Qizilbash, Sialkot to Jammu, 2018, Graphite and wash on water color board

In the dimly lit room at the back of the second floor is a separate exhibit featuring another Pakistani artist, Ghulam Mohammad. Although not part of Intricacies, perhaps Mohammad’s works can be seen as a fragment of it, changed by and changing the whole. The centerpiece, Tana Bana (Fidget) (2019) is described as “paper woven carpet.” It lies at your feet, delicate and large. You bend down to see that the cut paper has Urdu words printed on it. The words are broken off and meshed together by the weave. The language’s meaning is lost where the edges of the paper join and overlap, creating new letters, new words, new language. Though the meaning has been utterly deconstructed, the resulting arrangements, the randomized calligraphic strokes, form a design more beautiful and more entire in its own right than its individual parts.

And Hung on the walls, more curious even than paper carpet, are what seem at first glance to be fabric swatches. But, looking more closely, what appear to be fibers are actually letters—hundreds of individually cut-out letters. What words these letters originally formed, and what sentences those words shaped—what ideas—are lost now. Now they are intricate fragments, part of a new whole, with meanings still to be deciphered.

—

Intricacies: Fragment and Meaning

Exhibition: August 8 – September 14, 2019

Ghulam Mohammad | Gunjaan

Exhibition: August 8 – September 14, 2019

Aicon Gallery, 35 Great Jones St, New York, NY 10012

—

M. Sullivan lives in Brooklyn.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)