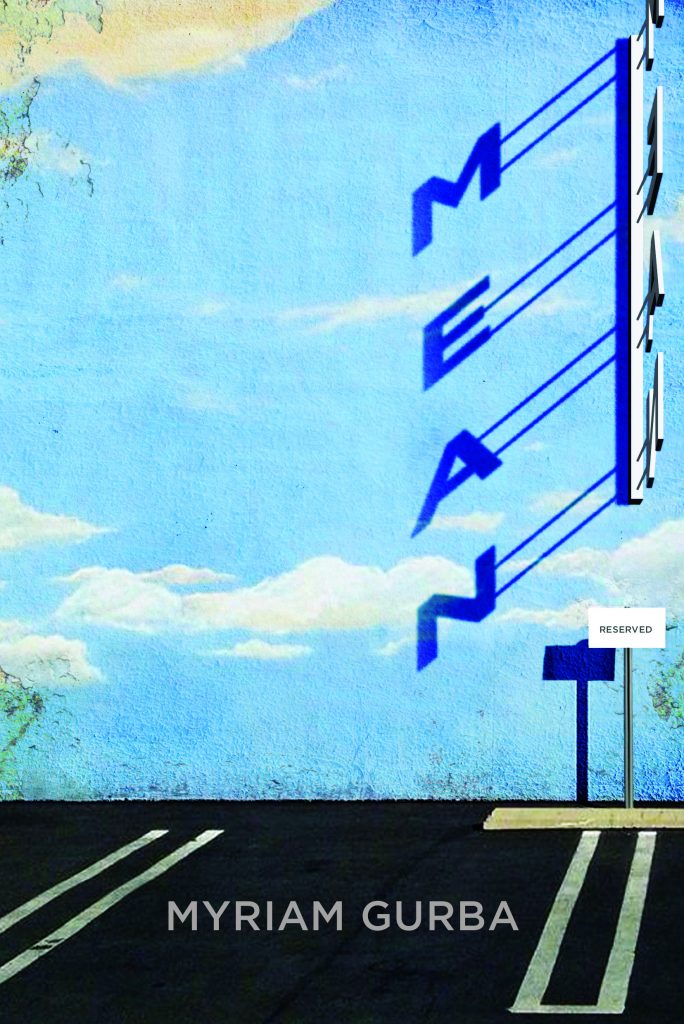

(Coffee House Press)

BY NICHOLE L. REBER

—

It’s hard to say which quality makes Myriam Gurba’s Mean such a stellar read. Her dark sense of humor? Her unique perspective as a queer Chicana from California? It could also be her structure. She compels the reader through her nonfiction novel without letting us merely settle into the book as entertainment. Instead she engages our intellects, which makes an altogether enjoyable experience.

Gurba weaves topics together in the forms of found poems, prose poetry, news reports, memoir, and lists. Once we’ve connected enough strands we see patterns emerging: racism, misandry, class, and sexuality.

The story begins with a young, petite Latina with long clothing walking in a Little League baseball diamond at night. A man follows her, chases her then bludgeons and rapes her. News reports leave her nameless, call her a transient. Gurba finds out this woman’s name is Sophia (Torres) like Sophia the capital of Bulgaria, like Sophia Loren, like the Sophia in the Bible; she’s 5’2” and Mexican, and the young migrant worker had already had a rough life before it came to a close there in Oakley Park, not far from Gurba’s house. It’s what the two women have in common that allows readers to connect the strands Gurba weaves into a larger picture, especially in the chapter “Strawberry Picker,” where we see race, misandry, and class.

“Sophia is always with me. She haunts me.

“Guilt is a ghost.”

Guilt ties in to the multiple meanings of privilege Gurba shows us. Daughter of a Mexican teacher/mother and half-Mexican school administrator/father, she and her siblings enjoy a middle-class life. There’s a large gap between her family and the Mexican migrant workers who pick produce in the California fields. Privilege, she intimates, isn’t just for whites.

Privilege doesn’t, however, equal invincibility. It couldn’t save her sister or Gurba herself from eating disorders. Nor could it shield her from the grade school classmate who repeatedly molests her and fellow female classmates; or the history teacher who, despite witnessing the boy’s actions, does nothing. Nor could it shield her from having an unfathomable empathy for Sophia Torres.

Not all is tragedy though. The author’s sense of humor gives this book an equal amount of levity. Sometimes that means taking pot shots at race and gender: “Of course an elderly white dude taught anthropology,” she writes in the chapter “Nicole.” “Who better to explain all the cultures and peoples of the world than he who is in charge of them?”

Sometimes humor means taking pot shots at sexuality, eating disorders, feminism, misogyny: “Good girlishness resists pleasure. Good girls prove their virtue by getting rid of themselves,” she writes in a Catholic-heavy chapter. “Death by anorexia is a fail-safe sexual-assault prevention technique,” a line that reverberates like a nail-studded boomerang later in the book.

Gurba continues to bust balls, provoke, and raise readers’ eyebrows throughout the book, and she traverses a vast world. She takes us from the Japanese style of art known as Ukiyo-e, her great-great-grandfather’s role in a 19th-century Mexican revolution in support of Communism, and masturbating to the Diary of Anne Frank. She makes us ponder what would make an appropriate gift for the grave of the rape victim. Even Michael Jackson makes an appearance.

Read Mean for its humor and stimulating structure. Read Gurba for her unique perspective and literary stylings.

—

Nichole L. Reber picked up a love for world lit by living in countries around the globe. She’s a nonfiction writer and her award-winning work has been in World Literature Today, Ploughshares, The Rumpus, Lunchticket, and elsewhere. Read her stories on a Chinese cult, wearing hijab in India, and getting kidnapped in Peru at http://www.nicholelreber.com/.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)