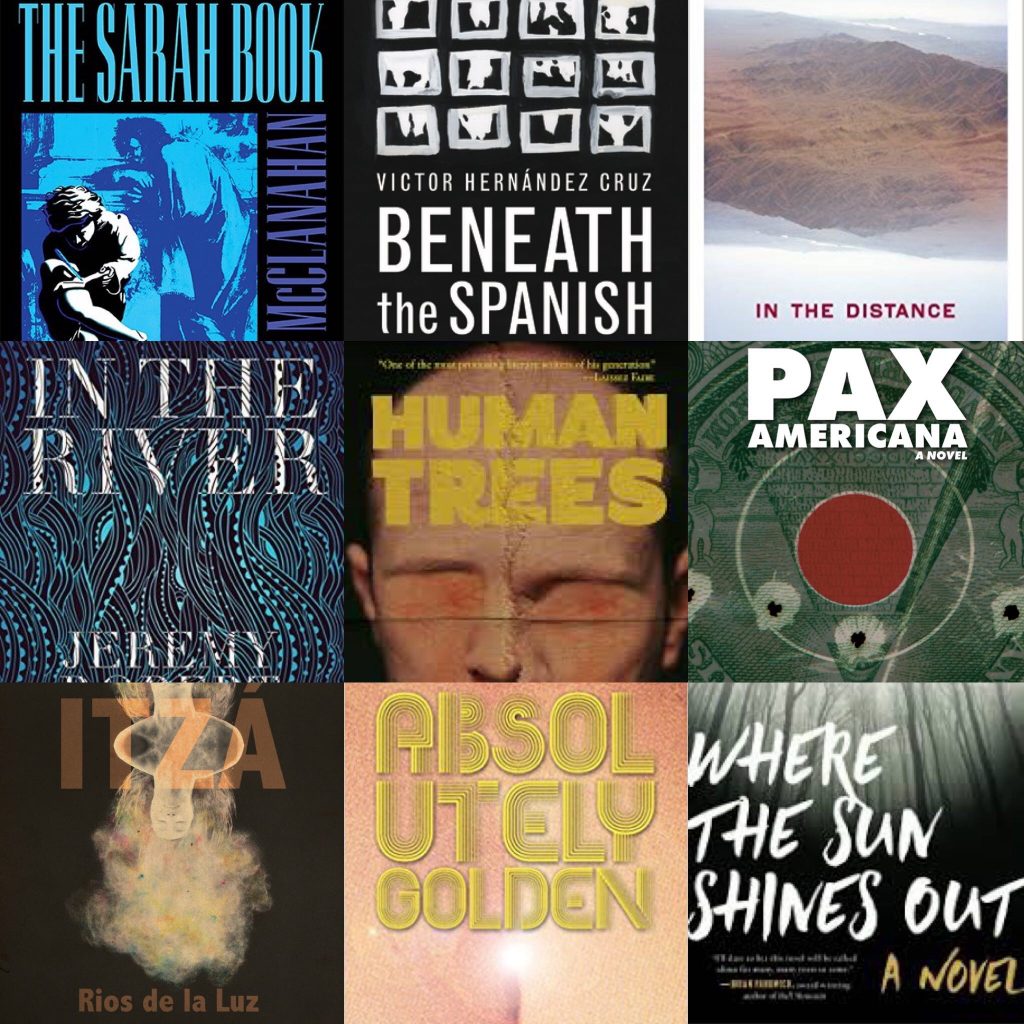

The year is almost over and it’s time to revisit some of my favorite reads of the year. As with any list, this is not as extensive/inclusive/comprehensive as I’d like it to be, but having to do other things besides reading severely cuts into the amount of time I can spend inside books (if you have any leads on a gig that pays you to read whatever you want, get at me). In any case, this was a fantastic year. I made a list of best crime reads and one of best horror books, but some of the best books were in the enormous interstitial space between genres. Anyway, here are some books I hope didn’t fly under your radar:

Where the Sun Shines Out by Kevin Catalano. I was ready for this to be great, and it was, but the pain and violence in its pages blew me away. This is a narrative about loss, guilt, and surviving, but the way Catalano builds his vignettes allows him to show the minutiae of everyday living and the sharp edges of every failure.

Absolutely Golden by D. Foy. Funny, satirical, smart, and packed with snappy dialogue and characters that are at once cartoonish and too real, this is a book that, much like Patricide did last year, proves that Foy is one of the best in the business and perhaps one of the most electric voices in contemporary literary fiction.

I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do) by Tatiana Ryckman. I met Tatiana when we read together at Malvern Books in Austin in late 2017. She read a chunk of this and it blew me away. I got the book that same night. Imagine your favorite philosopher deconstructing weird relationships while trying to simultaneously make you cringe in recognition and laugh at yourself. Well, this is what that philosopher would write. A short, powerful read that I will soon be reviewing here in its entirety, this was a blast of fresh air.

Itzá by Rios de la Luz. This short book destroys patriarchal notions of silence, abuse, and growth. Rios de la Luz wrote about a family of water brujas and in the process redefined bilingual bruja literature. This is a timely, heartfelt book that celebrates womanhood in a way that makes it necessary reading for every gender.

Pax Americana by Kurt Baumeister. With Trump in the White House, this novel is more than an entertaining look at the dangers of unchecked religion and politics. Yeah, call this one a warning that should be read by all. It’s also very entertaining and a superb addition to the impressive Stalking Horse Press catalog.

The River of Kings by Taylor Brown. I don’t want to imagine the amount of research that went into this book. However, I’m really happy that Brown did it, and that he turned everything he learned into a novel of interwoven narratives that is a celebration of a river, of people, and of language. This was so stunning that Brown immediately joined the ranks of “buy everything he publishes authors” before I’d reach the tenth chapter.

Human Trees by Matthew Revert. If Nicolas Winding Refn, Quentin Tarantino, and David Lynch collaborated on a film, the resulting piece of cinema would probably approximate the style of Revert’s prose. Weird? Yup. Smart? Very. Beautiful? Without a doubt. It seems Revert can do it all, and this is his best so far.

In The River by Jeremy Robert Johnson. The simple story of a father and son going fishing somehow morphs into a soul-shattering tale of anxiety, loss, and vengeance wrapped in a surreal narrative about the things that can keep a person between this world and the next. Johnson is a maestro of the weird and one of the best writers in bizarro, crime, and horror, but this one erases all of those genres and makes him simply one of the best.

The Sarah Book by Scott McClanahan. A slice of Americana through the McClanahan lens. Devastating and hilarious. Too real to be fiction and too well written to be true. Original, raw, and honest. Every new McClanahan books offers something special, and this one might be his best yet.

In the Distance by Hernán Díaz. This is the perfect marriage of adventure and literary fiction. The sprawling narrative covers an entire lifetime of traveling and growing, and it always stays fresh and exciting. At times cruel and depressing, but always a pleasure to read. I hope we see much more Díaz in translation soon.

Beneath the Spanish by Victor Hernández Cruz. Read the introduction and you’ll be sold on the entire book. Multiculturalism is fertile ground for poetry, and Hernández Cruz is an expert at feeding that space with his biography and knowledge and then extracting touching, rich poems and short pieces that dance between poetry, flash fiction, and memoir.

Some other outstanding books I read this year:

Dumbheart / Stupidface by Cooper Wilhelm

Inside My Pencil: Teaching Poetry in Detroit Public Schools by Peter Markus

Something to Do With Self-Hate by Brian Alan Ellis

Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions by Valeria Luiselli

There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé by Morgan Parker

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

The Yellow House by Chiwan Choi

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)