Soft Skull Press

November 2016

300 pages

REVIEWED BY Hollynn Huitt

—

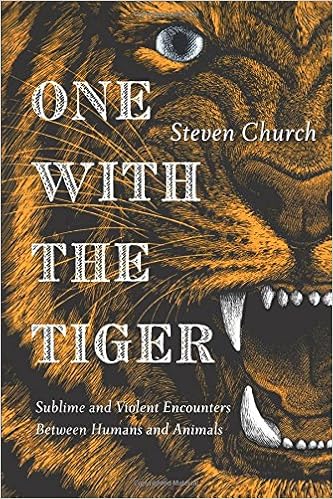

Steven Church is betting that you’ve stood outside of a lion enclosure at the zoo and, for at least one long second, thought about jumping in. But not because the lion is cute, or looks like a big, sweet cat lounging in the sun. You want to jump in because you’re afraid, deeply afraid, and that fear draws you to animals like a magnet. One with the Tiger opens with the story of David Villalobos, a young man who jumped into the tiger enclosure at the Bronx Zoo, where he was promptly mauled. Church has a casual and compelling style of writing, and the opening chapter seems to be setting us up for a deep dive into David’s psyche when he jumped into the cage. And the book does do that, in it’s own way, although not by interviewing David, or diving deeper into the story. Instead, David’s dangerous compulsion is the starting point for an in-depth exploration of what it means to be drawn to, and get too close to, dangerous and wild animals.

The book is split into 8 sections, each one loosely themed around an incident involving humans and animals, or humans behaving like animals. Take the “Timothy Treadwell” section, which focuses on grizzly bears–both the author’s personal experience and the documentary and the enigma of Timothy Treadwell, star of the Werner Herzog documentary, Grizzly Man. Church is exceptionally gifted at writing about movies–his spare but warm style gives lends just enough detail to make you feel like you’ve seen the movie, and his enthusiasm about each of the scenes he describes in One with the Tiger is contagious. I watched Grizzly Man after reading and honestly preferred Church’s description and analysis to the actual movie.

Church brushes on the innate savagery within humans as well, in his chapter “Iron Mike” (roughly organized around Mike Tyson’s ear biting of Evander Holyfield) and how we are little more than raving raging animals underneath all of our culture. This part of the book is full of boxing facts, which can get tedious, but is ultimately carried on the strength of Church’s skillful weaving of real life events, movies and literature in a snappy, easy-to-read digest.

But it’s the third category of incident that Church is most fascinated with, the one that David Villalobos presented to us at the beginning of the book–people who willingly go into cages or environments with dangerous animals with not because they want to die, but because they they feel an almost indefinable pull, perhaps because of adrenaline, or because it’s forbidden. Church is obsessed with this particular demographic, in part because he has felt the call, and he’s betting that you do, too.

The book an easy and fun read, and strangely holds together, despite being fragmented into parts and missing a basic narrative arc. We subconsciously hold out hope for a plot twist at the end: that Church will step into a cage, or that he’ll be able to speak with David Villalobos. Maybe then he could clue us in on something we couldn’t read for ourselves in the news or media. But instead he is relegated to rehashing news clippings and interviews. Church’s subject matter, horrific and compelling in a train accident sort of way, is the strongest quality of the book, and he handles it without machismo or affectation. He’s just a regular guy trying to come to terms with the strange obsession he feels and by the end you’ll be looking at the world–the world of dangerous animals at least–in a whole new way.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)