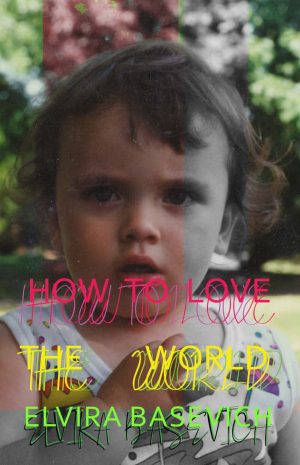

Set just before the collapse of the Soviet Union, HOW TO LOVE THE WORLD is at once a condemnation of the world, a daydream of America, and an unsent love letter—written and rewritten over the course of ten years—to a dead family. A meditation on intergenerational trauma, resilience, and hope, HOW TO LOVE THE WORLD is written in the tradition of epic poetry and follows the author as she retraces her mother’s journey to New York City in the summer of ‘89.

PANK: One line from the poem “A Universal Map of the Womb” stuck with me—there’s a moment where the speaker and her mother are waiting in line for a fast-food lunch in Brooklyn. As she pays for their cheeseburgers, she says, “Now, let’s be like normal people.” What’s the normal that these two figures are reaching for in this book?

ELVIRA BASEVICH (EB): That is a verbatim quote. My mom would often say it when I was a kid. I thought I understood what she meant, but the more I tried to do “normal” things with her and express “normal” feelings, the more I felt like we were drifting away from other families, as I was trying to understand how to build intimacy with someone so traumatized by their past. Is it normal to write a long goodbye to a loved one in the form of a book of poetry? It is for me, I don’t know about other people.

I do know that the most normal thing is also often the most extraordinary if we really take the time to understand what motivates us. To love someone fully—in the light of the specificity of their character and yours, of their past and yours—is the most demanding project that you can ask of yourself, one that can require extraordinary creativity and grit. And if each person faithfully applies themselves to the project of loving (and living) fully, I am not sure how much convergence there will be to recast our collective conception of normalcy.

It can be liberating to let go of conventional ideas. In that sense, quoting my mother was meant ironically in that we would never accomplish normalcy, at least not according to external standards, even if we also eat at McDonald’s, watch sitcoms, and I send her flowers on her birthday. We would never be or think or act like other people. And that’s OK too. Often being different for us felt like a sign of failure or weakness. It is gratifying and sometimes simply necessary to let external standards go. Individuality can then flourish.

PANK: How has Nabokov influenced your work? I found myself struck by references and lines throughout the How to Love the World that called to mind Speak, Memory— the opening poem, for instance, declares ‘I am your baby girl, Mnemosyne’– and the text fluidly incorporates Russian epigraphs and phrases.

EB: You are an extremely careful reader of the book! I had finished Nabokov’s Speak, Memory just a year or two before completing How to Love the World and was referencing it in the opening poem, “Invocation of the Muses.” Nabokov is a genius.

This project, as well as my next poetry book, is in conversation with Soviet and modern pre-Soviet Russian literature, art, and culture, particularly Pushkin and the poets of the Silver Age popular before the Bolshevik Revolution. I am also consciously situating my work among writers of the Jewish diaspora, both living and dead. This is the context where I feel most at home—my literary imagination lights up. I still have so much I want to say, even as I keep returning to the same themes of family, exile, memory, religion, and loss.

I should add that what particularly resonates with me about Russian modern literature that I admire is the robust role of ancient Greek and Roman poetry. I have been fascinated by the idea of “updating” the genre of epic poetry for the contemporary world, told from the point of view of the most powerless and underrepresented voices, such as refugee women and girls, rather than blood-hungry, violent male “heroes” who through the passage of historical time still seem to have a pantheon of pagan gods on their side.

I remember that when I was a freshman at Hunter College, CUNY, I took an introductory class on Greek and Roman mythology. My brilliant professor said, almost in passing, that there have not been any women who have written epic poetry. I took it as a call to action. I decided then and there as a seventeen-year-old that I will be that woman. It is extremely gratifying to know that I kept that promise to myself.

PANK: How to Love the World builds a picture of American experience that’s filtered through refugee and first-generation lenses–arguably the most American identity out there. What’s the most American day you can remember having? Where did you go / who did you see / what did you eat? Who would you invite to re-enact it with you if you could?

My partner recently hosted a Super Bowl party. He is from Hudson, Ohio, and is a huge sports fan, which I find really endearing. I told him that I’d never been to a Super Bowl party before and had always wanted to go! He asked me what I expected it to be like. In response, I said jokingly that I always imagined orange food. And so, he bought Cheetos, cheddar crackers, and cheese dips. Nothing quite makes you feel American like eating orange food while watching the Super Bowl. It was amazing.

I have started writing my next poetry book. It is tentatively titled Cars. In it, I play with the juxtaposition of Soviet and American highways, manufacturing processes and labor rights, the funny names for car parts and types and models, and the values associated with the commodities that define the ideals of a people and a place. For “research,” I have been talking to my partner about that a recent trip he took with his dad to see the Daytona 500 NASCAR race in Daytona Beach, Florida. It’s been really fun—a very different writing process, compared to my first book! I feel like somehow the writing is bringing me closer to America, even as I continue to think about the idea of “cars” in the Soviet Union.

PANK: How to Love the World functions as something of a palimpsest: personal history overwritten with family history, refugee experience, the long slog through trauma, a fraught relationship with a mother. The book is even broken into Book I and Book II– there’s a distinct before & after that placed the emotional journey of reading as a mirror to the physical journey of the emigre. There is a lot of narrative meat here. Why poetry? What did poetry allow you to accomplish with this book that, say, memoir could not?

I will eventually write a memoir, I know, as well as a historical novel loosely based on the life of my paternal grandmother. But save for Angela Davis and maybe Greta Thunberg, I cannot imagine a memoir written by a twenty-something-year-old having much value. I knew I had to undertake the project about my family and my past—I could not wait that long. My writing of How to Love the World was urgent, even though it took me a decade to write it. I have found that poetry is the most effective way to communicate—and transcend—one’s own experiences. And for that, I will always be grateful to poetry.

I am a voracious reader of novels and it reflects in my poetry. I also love poetry books that tell a story with a complex narrative structure. Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic is an excellent recent example.

PANK: This book took ten years to write. What would you say to someone embarking on a similar course with a project? Any advice for the journey?

EB: Just. Keep. Writing. There is no other special trick to pull the white rabbit out of the top hat.

And have faith in your voice.

Know that you will finish the project and it will feel wonderful when you do. On a more practical level, as the project moves along, it is helpful to have a blueprint of where you are going and how you plan to get there in the literary execution. For example, which styles would you like to experiment with, whose voices would you like to engage and incorporate, what time of day is best for creative writing?

PANK: If you could upload one text into the brains of your readers Matrix-style before they opened your book, what would it be?

History: A Novel by Elsa Morante.

PANK: Anything else you’d like to share with [PANK] about How to Love the World? [PANK] loves you!

Thank you for giving my first poetry book such a warm literary family—

—

ELVIRA BASEVICH is a poet and assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. Her poems have recently appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Poached Hare, TriQuarterly, The Gettysburg Review, and Blackbird.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)