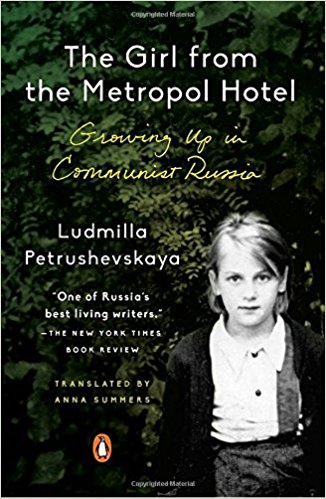

(Penguin Books, 2017 in English)

INTERVIEW BY MIKA BAR-ON NESHER

__

The Girl from The Metropol Hotel is a thin book that contains within its short vignettes an unspeakable terror: the collective memory of Russia during WWII and the turbulent decades that followed. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya family belonged to a long line of prominent Bolsheviks who were labeled “Enemies of the State” during The Great Purge. They were brutally murdered. Cast out of the luxurious Metropol Hotel, a former Bolshevik headquarters, the few remaining women of Petrushevskaya’s family were stricken with political stigma and forced into the darkest outskirts of Soviet society. It is in this setting we encounter the voice of the young Ludmilla. Starving with a bloated stomach, searching for potato peels in the trash of a violent neighbor, she wanders the streets of Moscow barefoot in winter singing popular songs or reciting Gogol for alms. She loves books, though they are hard to come by. Her grandmother knows them by heart and recites. Though she displays exceptional academic talents, she is kicked out of every school because she is wild, untrainable, and consistently places her freedom above all else. This young child not only survives but possesses the power to make the terror beautiful with her unique imagination, to turn tragedy into a story, carving out a context for an entire nation’s loss to rest within and remember.

My Skype rings imitating an old phone. I’m waiting for Anna Summers to answer. Born in Moscow, Summers earned a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures from Harvard; this is the fourth book she has translated by Petrushevskaya, the first memoir. She tells me about her first encounter with her work as a young teenager. During Perestroika, her previously suppressed work had begun to come out little by little, Summers describes the effect it had on her as life-transforming, “I hadn’t imagined one could write like that on that kind of subject.” Summers’ voice is warm with deep respect and love for Petrushevskaya, it’s contagious.

A hybrid memoir, feat The Girl from The Metropol Hotel features drawings, images of Soviet structures, and photographs of Petrushevskaya’s family which were selected and curated by Summers to illustrate what she calls “that long vanished world”. Despite being an autobiography, and in many ways a historical account, there runs an undercurrent of magic and fable throughout the chapters. Summers explains to me that Petrushevskaya loves fables and they play an important role in the Russian literary tradition. Fables and fairytales give shape to unnameable fears, the fear of death can become a sorcerer, loss may take the form of a poisoned apple.

“Russian fairy tales are like no others” Summers explains, “They are both very formulaic and full of individual little detail. In that, they resemble Russian religious icons that follow the same established pattern but at the same time full of individuality. The most common theme is loss. One loses a favorite object, a child, a husband, a bride—often for some silly reason. And then one looks for it—for years. One overcomes countless obstacles, fights monsters, wears out seven pairs of iron shoes—and only then, at the end of seven years of suffering regains what should never have been lost. This narrative structure—loss followed by a long hard road towards recovery–is very much part of Russian mentality

“Have you ever watched Oliver Twist?” she suddenly asks.

“I’ve read the book”.

“Okay, but you should watch the musical” Summers goes on to. “It’s one of the scariest stories ever written, about a child abandoned, betrayed, tortured, starved, abused in every possible way. But the musical, which is a theatrical form that would appeal to Petrushevskaya, turns the most gruesome scenes into magical sing-and-dance numbers. Because they are seen through the eyes of a child, and to an imaginative sensitive child the world, even the world of gangsters, war, starvation, and injustice is always full of poetry and magic to this kind child.”

Today Petruvaskaya lives in Moscow, at seventy-nine years old she is famous for her paintings, books, and more recently a career as a cabaret singer. Her courage and resilience has helped an entire generation of war children express what was mute and unspeakable. The book shows a young girl who never gives up her power, never checks the resonance of her powerful voice. As child she was a political outcast, but the power of her genius kept her intact. She never cared about publishing or fame, she has been a consistent pillar, always herself, forever attuned to finding the beauty in any setting and the truth in every story.

__

Q&A with Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

Translated by Angela Fox & Christopher Jeffrey

Mika Bar-On Nesher: What was your process like when working on this book?

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya: I wrote that book–as it happened–when my aunt Vava was dying. She was 93 years old and it was her first time in a hospital. She was very upset there. I, too, found myself beginning to die. I couldn’t eat. I lost 14 kilograms during the time of her gradual deterioration. Every single day, I was writing The Girl from the Metropol Hotel, and I was feeling such guilt, that at 9 years old, I had run away from them with my grandmother. Vava had already completely lost her memory, and I visited her to put her to sleep. Together with the nurse, I changed her clothes, tucked her in, mumbling to her, as a mother to a child, despite knowing that she didn’t understand anymore. And suddenly, she wriggled out (slipped out) with some strength and kissed my hand. And I thought, that I would never let her read my book.

A writer doesn’t control his or herself – I don’t, in any case. I have the impression, that from the first moment of a work, the entire text is already sitting in my head, from the first to the last word. So, this type of process that you’re asking me about doesn’t depend on me. I don’t control this dictation. It comes all on its own. It’s up to you to catch it and write it down. That’s why I always carry a notebook and pen with me. One time, a story came to be, but I was on the metro, in a crowd. And I didn’t have a pen. I arrived home, but to my complete despair, the story had gone. Only the following day, already at work, I went to the library, and by sheer willpower, knowing the story’s content, I forced it back. But it was already a different version. The poetry was gone. The rhythm was gone, the intensity, the word order, that can only be brought on by inspiration. By the way, one critic wrote that if stories match with their rhythms, then they are vers libre… but I thought in response, that’s a very long vers libre. You know, I very rarely edit a written text. I believe that it has been dictated to me as it’s meant to be. It can overtake me anywhere – on the street, on the train, in a store. Besides, as a rule, every tale is a true story. It’s true, the characters do not recognize themselves, I crucially change the surrounding circumstances. Regardless of whether the text is magical or far removed from reality – like in the book There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby, for which I received the World Fantasy Award in the U.S.A in 2009. All the things in that book were also written down instantly, at once. When I was raising my children, in the neighboring room lay a sick mama, and so I got to work, right away. Now, I live alone and time started to drag. I’ve almost finished two books, but I wait for the right moment to finish them. The finale of one of them, by the way, is inspired by a James Bond film.

MB: You are one of those rare artists who possess the ability to express yourself in writing, music, and painting. What is the limit and benefit of each medium for you?

LP: I draw constantly on a scrap of paper or in the notebook that I’m writing in. These sketches – just hand movements, some sort of profiles, and then it appears to me – I seem to be making up some sort of stories with these characters. This is how many children behave, they draw, they create and compose. But serious work – watercolors, illustrations for my books, comics, cartoons, portraits, pastels, engravings – for these endeavors it takes a whole day, or even a week, when I cannot spend time on anything else. Over the last few years, I started to sell my work, to raise money to support disabled orphans whom I take care of. Harvard University’s library has purchased 21 of my works, and the proceeds support these children.

As far as the concerts, it seems, I am a born actress, who sings for morsels of bread (like Edith Piaf). This ability to stand before people and sing has long sustained me. I performed on school and university stages. And I even earned acceptance at the Conservatory, since my youth I developed a strong voice with a three-octave range. The concerts were held in grand halls, and from those experiences emerged my passion for being in front of an audience. But I stopped making appearances. Then, I only sang songs for children – or in the summer in the fields when no one could hear me, I’d perform an operatic aria. I’d scare the hares. But I was always singing at home, sitting at the piano, when no one was around. Mainly French chansons. I recorded myself with a tape-recorder, then I’d listen. I’d erase it, and record again. I was trying to sing in my own way somehow. I taught myself on my own. After all, in private singing, you don’t need a strong voice. More important, you must find your own style, your own individuality. And suddenly, again I returned to the stage at 69 years old. It was World Theater Day, and we were celebrating in a small cafe; after all, I am a well-known playwright. Everyone came – my actors, directors, my fans and students. And I decided among these acquaintances and dear listeners to sing four songs in French. I was, all the same, terrified. But as I began to sing, I suddenly realized, that the joy of the audience was beginning to move me – to my left and to my right, we were all together in the music! All of us! In that moment, my fear left me, and in its place, happiness arrived – I returned to the stage and began to give concerts, I assembled my own musicians and formed the Kerosene Orchestra.

I began to compose my own songs. Waking up in the morning, already fully formed melodies sounded in my head. Ability arises in a person when it is needed after all… and writing the words to a song, that I could do. I am a poet, I’ve filled books with verses. Above all, I began to write songs like monologues, like little one-woman shows. Mostly about lost love. Of course, there are lots of songs about that.

I’ve toured all of Russia with my concerts. I’ve sung in New York (at the Russian Samovar), in Sao Paulo, London, Paris, in many European cities. I not only sing, but I read my rather amusing poems. I design my own hats, rings, dresses. I do my own makeup. The stage – it’s such a joy. And I consider my show to be my very own.

MB: Were fictional characters that inspired you and shaped your worldview as a child?

LP: What books influence you? Which literary heroes? For me, I drew inspiration not from books, but from the children’s groups in the summer camps and in the tuberculosis sanatoriums, where there was one caregiver for every thirty children. And we were alone in the bedrooms. And all throughout the night, I was telling scary stories. I made them up. But the collective is stern and educates children what not to do, according religious traditions – thou shalt not brag, thou shalt not be proud, thou shalt not lie, nor steal, nor sin. Thou shalt not be smarter than others, nor more talented than others. And the punishments are severe. But I always performed in the children’s shows, sang in the concerts, drew in the studios — that was my answer to the collective. I was beaten. I answered. Art is the only place for the outcasts, for the poor, for those who have it worst. The collective opinion cannot conquer them, they can only be ruined by their own inclinations and weaknesses. Alcohol, narcotics. How many of my colleagues, young writers, are dead. Even I, myself, smoked, and at gatherings of all kinds drank wine, and then, when I was pregnant at 37, I quit it all. I stopped eating meat too. But…

MB: Can you tell me what it was like when you first started trying to get published Russia?

LP: I began writing at the age of 30, and my first story “Such a Girl, The Conscience of the World”, immediately went out to the public, and was mass copied, reprinted on typewriters. But everyone said that they would never publish it. It was published twenty years later. My first play (written in 1973) was forbidden for more than ten years – “Music Lessons”. And my second play – “Love” (1974), was permitted in 1980 and immediately was picked by the three biggest theaters in Moscow. And at 50 years of age, in 1988, came my first book of short stories with a circulation of 30,000 copies. That book, by the way, sold out in a few days. But even after I was widely known, my stories and plays were retyped by different people and were passed from hand to hand. Perhaps, back then I was even more well-known than today. Actors put on my plays in apartments…

MB: Do you have any advice for young writers and artists?

LP: One word of advice – listen! Listen to those who tell the story of their lives. There are many of them. Remember, HOW these people talk, and remember each person speaks for themselves. All of a sudden, someone’s story will hook you and it will lead you write.

__

Mika Bar-On Nesher is multidisciplinary artist and writer based in Brooklyn & Tel-Aviv, she studies creative writing at the New School.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)