The Up Drafts is an ongoing series of essays and interviews that examine creativity, productivity, writing process, and getting unstuck.

—

BY NANCY REDDY

At the end of 2019, it seems like all of writer-twitter was consumed with counting up the decade’s achievements. There’s a variety of approaches: the straightforward list, the list with mock-items sprinkled in, the list that ends with a kind of coy wink, but everyone, it seems, felt compelled to count. (Except Morgan Parker, who tweeted the extremely accurate assertion that “this decade I did a lot.”)

Can you hear the buzz of anxiety beneath all that accounting? It’s useful to be able to prove quantitatively what you’ve done – but I also wonder why there’s such widespread obsession with proving ourselves. Okay, I don’t actually wonder – economic anxiety and the ever-escalating precarity of journalism and literary publishing seem like obvious culprits – but I do think it’s worth interrogating all this counting. When you count your accomplishments, is there some number that is enough?

The counting that’s stuck with me the most slightly predates the current new decade fever. In Real Simple Taffy Brodesser-Akner (of GOOP profile fame) spends a full paragraph counting up the many successes of a very good year: 90k words published in The New York Times for 12 different stories, 40k of a new novel (sold before its completion), the publication of one of the most talked-about novels of the year, Fleishman is in Trouble, as well as a number of friends and family-related activities, which I skip over every time I read it because really I re-read that paragraph to be daunted and inspired by Brodeser-Akner’s relentless hustle. When I re-read the article to write this essay, though, I realized I’d misremembered. The phrase I’d heard as central to the essay – Brodesser-Akner invoking all this accomplishment, as if she’s rubbing her hands beside the warm fire of her word count – isn’t in the essay. Brodesser-Akner’s actual phrase is the somewhat more muted observation that, in lieu of the zen mindfulness we’re often encouraged to aspire to, “I had accomplishment, which was my own form of peace via a longer game.” (Once you’ve published nearly 100,000 widely-read words in The New York Times, I guess you don’t need to add all this to your accomplishments.)

In any case, I love invoking accomplishment as an alternative to productivity. I’ve been very productive at many moments in my life: writing a dissertation in a frenzied 18 months, during which I also conceived and birthed a second kid and went on the academic job market, for example. But thinking in terms of productivity–obsessing over word count or crossing items off a task list–can also mean substituting busyness for meaningful work.

As we start this new year in a new decade, I, too, am full of resolution and big ideas. Lately, for every thing I can count as finished–meaning published, or at least submitted–there are at least twice as many half-starts and dead ends. When I think about writing–all the essays I’ve started, the new book I’ve written a scrappy 25k of words and a query for–my brain gets stuck in pudding.

I’m starting this series, a bi-weekly exploration of why we get stuck and how we can unstick ourselves, in the hopes that I’m not alone and that what I’ve learned about the writing process and the trap of worshipping productivity will resonate with others out there in the writing-ether.

It feels scary, in this moment of internet-intimacy, to be taking a stance other than victorious or beaten-down but about-to-be-triumphant. Instead, I’m saying this: I’m stuck, but I’m working on it, and in the next several weeks, we’ll explore what it means to be stuck together. I’ll share what I’ve learned about accountability and process and switching writing medium when it gets hard, and I’ll share interviews with experts who can provide insights into creativity and writing process.

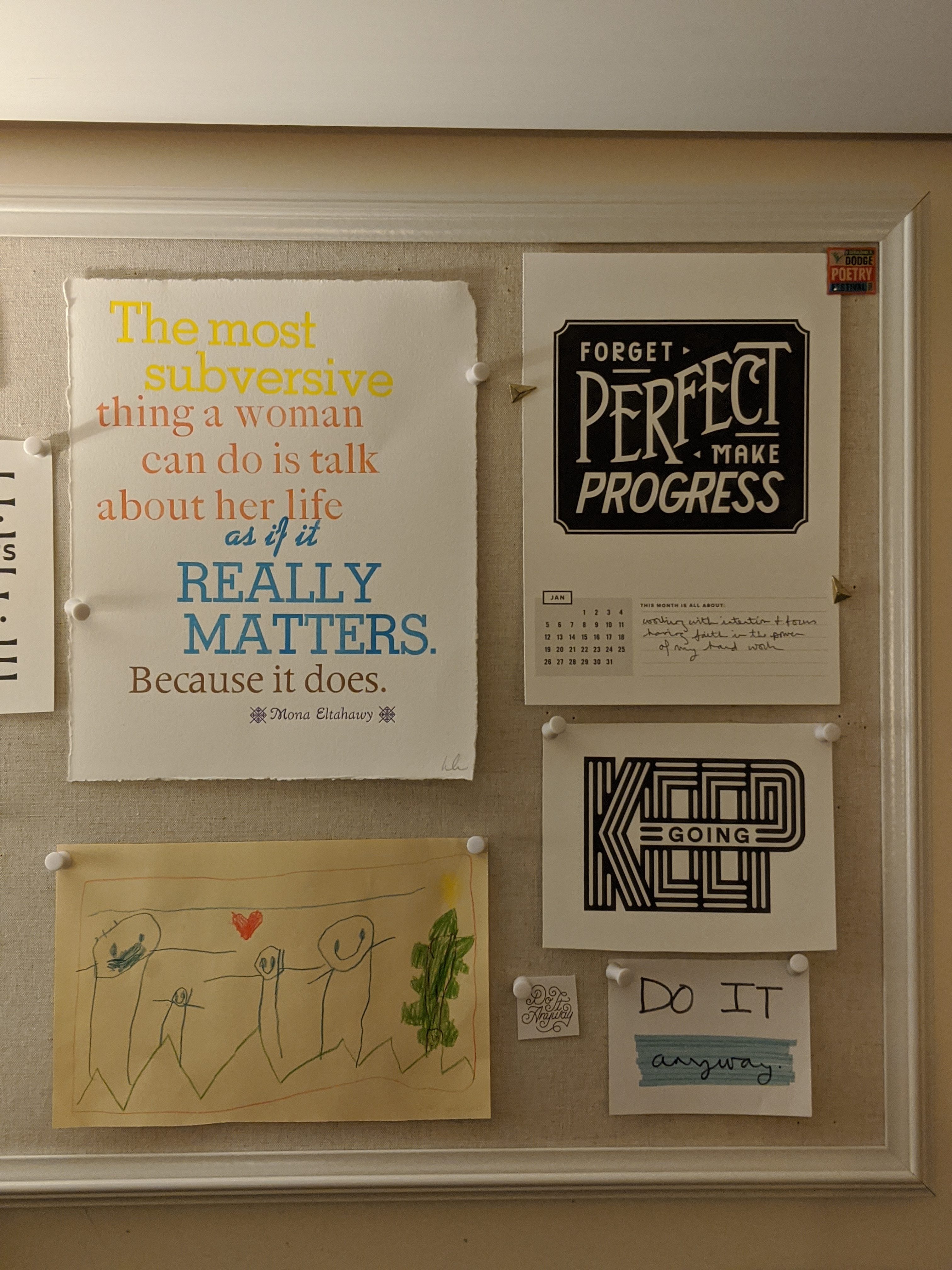

This series takes its title from a line from Anne Lamott’s widely-anthologized “Shitty First Drafts.” Lamott’s idea is that in your first draft, you’re just getting it all down, so that’s your down draft, and then you can go back and fix it up, making that your up draft. In these essays, I’ll be sharing my Up Drafts, the place where I’m working out ideas. In doing this, I’m thinking also of the joy with which my younger son creates: as I write, he’s finishing a drawing of a dinosaur (that’s me) walking a dog (we don’t have a dog) and carrying a baby dinosaur (there are no babies in our house anymore). He works on his drawings with a single-minded focus, but then he finishes them. He doesn’t obsess over color or line placement. He draws one dinosaur, then another; one joyous stick-family under a yellow sun and a heart, then another: all these accomplishments. He gives his drawings away, and then he gets back to work. In this new year, I’m trying to do that, too.

—

NANCY REDDY is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review, Pleiades, Blackbird, Colorado Review, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere, and her essays have appeared most recently in Electric Literature. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University. She’s working on a narrative nonfiction book about the trap of natural motherhood.

NANCY REDDY is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review, Pleiades, Blackbird, Colorado Review, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere, and her essays have appeared most recently in Electric Literature. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University. She’s working on a narrative nonfiction book about the trap of natural motherhood.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)