Review by Alan Zelenetz

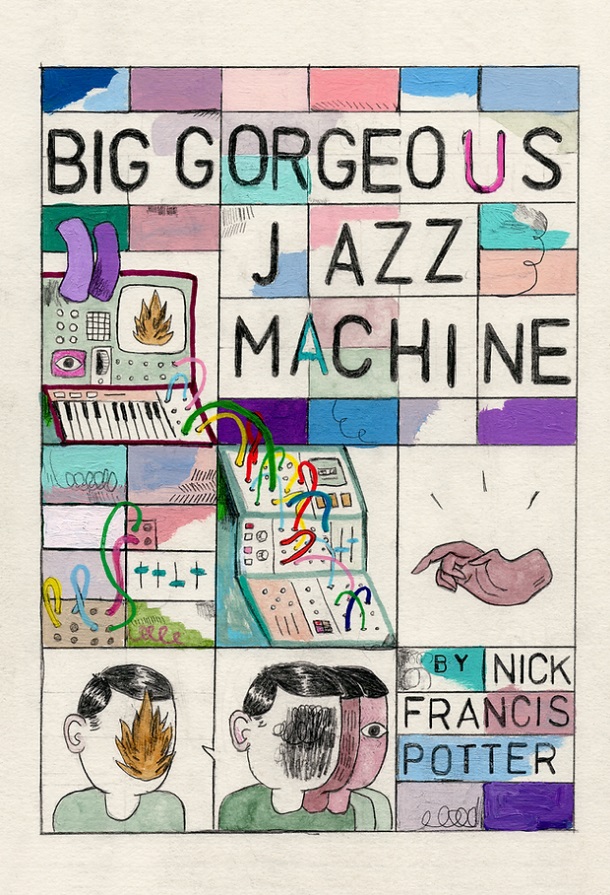

I’m imagining Charles Baudelaire shaking off his signature melancholy and “viewing” his way, for a devilishly delightful hour or so, through Big Gorgeous Jazz Machine, Nick Potter’s new collection of “Comics/Poems” (as it’s category-tagged on the front cover). No question, the nineteenth-century Parisian poet savors his twenty-first-century counterpart’s synesthetic blend of sound-sense-color-image splashing rhythmically across the book’s pages. And then, just before his return to the past, that sullen Frenchman tenders a nod of approval in fraternal recognition of Potter’s artistic vision. What vision? A dark-humored, offbeat scrutiny of the confounding dread and indecisiveness, the obsessions, hesitations, and foreboding uncertainties that constitute the human experiment on this fragile laboratory planet of ours. Global spleen.

To be clear, Potter is not pretending in this collection to plumb the philosophical depths of our existence, but he certainly is leading us, like anxious surfers at the shores of Teahupoo, towards some monstrously heavy waves.

Big Gorgeous Jazz Machine opens with a pair of erudite epigraphs, mischievously misquoted so that “comics” rise to the manifest aesthetic stratosphere of “music,” “architecture” and “geometric space.” First alert, we’re to be engaged in serious business here. What follows then is, well, to call it Comics Poetry is eminently fair, but. Perhaps a tad too easy? Semantically efficient, but. A bit cautiously genre-neutral? What the product of Potter’s creative process really merits—deservedly so and not for the sake of disruption—is that we tweak tradition and stre-e-etch conventional boundaries, like “Hey, make some room there.” BGJM delivers a combo of words and pictures metaphorically akin to nuclear fusion’s release of energy – so why not just call it what it is, “Sheer Poetry” and leave it at that? Sheer poetry vested in the verbal and visual, a marvelous marriage of past traditions and present day pop culture, of classic conventions and contemporary sensibilities.

In one spot the artwork reminds us of Renaissance sketchbooks, in another of French Fauvism; look over here it’s abstract, over there, representational. At one moment words appear as the integral and distinct elements of speech and meaning that we’d expect from daughters of the alphabet, at another they spring a surprise — fracturing into separate letters consigned to corners, or peeking out from a puddle of

colors, or—in grey calligraphy against grey background— playing hide and seek with us ready or not. Some words and letterstransform themselves into lines of art, improvising as they curlicue over and across comic book panels, challenging us to join all this jazz, to enter these boxes of poetry and endeavor to make sense of what we’re reading and looking at—or what we’re viewing, to attempt a term that might or might not better focus our attention on the graphic design, the fluid blend of text and image on the page.

And the poems we view leave little room for doubt that, all influences considered, we’re not in Da Vinci’s workshop circa 1500 or the Belle Époque studio of Matisse. Why, we’re even a whole century past Krazy Kat’s first comic strip appearance. We’re in the very here and now. Yes, in our own fraught post-aughts, where Potter casts an unerring and apprehensive eye on us humans in an absurd new millennium as we sink or swim to soundtracks by FKA twigs and Phoebe Bridgers.

Welcome to a world where vacationers, “People being who they are,” casually ignore a man who catches on fire, while the one woman who does respond intentionally adds gasoline, to extinguish the man, not the flames. An absurd fable fueled with a mean moral.

In this world, the eponymous Jazz Machine of the book’s title leaves a trail of suffering, chaos, and erasure in its wake, while a building’s infrastructure, rather than providing support, bends and hobbles and collapses into rubble.

Here, guests go missing and the disappearance of “Alvin Dillinger’s Brother” is conveyed by means of a worrying Beckett-like monologue with some wordless panels, several blotted black ink stains, and omnipresent forebodings of death.

As for Domestic Objects and Phenomena? Sinister. They portend Life’s design to fill us with recurrent dread, and they include uncertain dinner plans, dying plants, hidden wires, and threats by mom to sell our creature comfort television set. The unremarkable occasion of going for a haircut becomes a “Maybe” filled with indecision, hesitation, stuttering thoughts, and Kierkegaardian angst, all packed into a grid of claustrophobic rectangular panels better suited to an Excel spreadsheet—that product of dispassionate, dreary binary digits, over and over—than to capturing the relaxed atmosphere of an everywoman enjoying a pleasant talc-scented grooming.

And, yes, in this world, water is for drowning.

Not even an “Interlude” brings relief. In scratchy black and white, it suggests storyboards for the ill-fated fetal creature in David Lynch’s underground film Erasherhead. And by book’s end, the whole earth’s ecological catalog is reduced to smoke, flood, and cyclone. Despite a momentary hint and tint of some exquisite Japanese woodcut, we face a landscape bereft of animal life and a horizon devoid of any particular promise, fading off into a colorless “Epilogue” in grey and black and white, ovoid and jagged and wormy and flinty and sad.

Many of his themes may be dark, but Potter evidently enjoys plying and playing with the tools of his trade, all those letters and lines, words and crayons and colors and grids, fashioning them into his poetry, at times creating a sort of variation on haiku form.

“WHA/ T S/ HOULD WE DO/ A BO UT D IN NER ?”

reads across four panels awash in soft lavenders and blues, the words doing double duty as both semantic and graphic elements, the pictures not just sitting there looking pretty but propelling the narrative.

“A HIDDEN / KNIFE BUTTERS / MY HAND IN /THE LEAVES”

reads another set of panels, florally decorated and channeling the brevity, lyricism, elusiveness and, yes, pressed leaves of Emily Dickinson.

True, piecing together these poems requires a bit of cryptographer’s determination, and patience, but the rewards of penetrating the space of the panels, of “reading” into the Rorschach of Potter’s imagination and solving the puzzles he proffers are payoff enough.

Sure, the world might be a dread-full place. And, of course, we readers will recognize characters and circumstances on these pages all too well, as Taylor Swift intones in another context. Who hasn’t felt fretful at times? Boxed into the corners of an existential crisis? Fearful of an uncontrollable future, whether it be minutes, or months, or a millennium away? And yet, when a true artist interprets, depicts, and shares with us that world, those feelings—well, that, that is a joy-full experience. Such is George Potter’s Big Gorgeous Jazz Machine.

Alan Zelenetz is an East Coast – based writer and educator whose most recent publication is the collection Kull the Conqueror: The Original Marvel Years Omnibus.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)