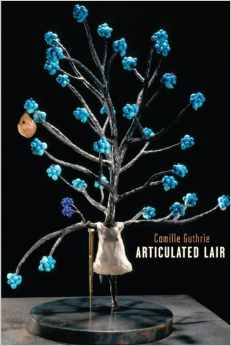

Subpress Collective

56 pages, $15

Review by Molly Sutton Kiefer

Louise Bourgeois is said to be a founder of confessional art; her sculptures are terrifying and stunning. In a discussion on The Rumpus, Guthrie revealed that Articulated Lair, which is named for an installation made up of a sequence of black and white angled dividers and a single black stool, started as a seed when she was in graduate school in 1996. These poems developed over the years, and while other projects shimmied forward faster, she continued to develop her LB poems gradually, returning in meditation, in compulsion. In the author’s note: “A desire to write about the Cells turned into a practice.” These Cells are a sequence of glassed- or caged-in sculptures surrounding found objects. I imagine Guthrie collecting stark lines on slips of paper, scattering these pieces on her kitchen table late at night, each slip lamp-lit, casting shadows just as the statues do.

The Cells act as a kind of anchor, taking up more pages than any other of Louise Bourgeois’ artwork. The Cells themselves are interactive—one peers into or walks into the art space itself, bringing forth the experience of the voyeur as the seer looks upon personal and found objects meant to evoke pain and fear. The gaze, then, is implicit in the poems, and reversed in lines such as “target-hearted / refracting a silver-gate” and “the second-mirror / eclipses your thoughts / promising vanities.” There is a looking-back, an importance of reflection.

Without accompanying art objects, Camille Guthrie’s Articulated Lair is a sequence of sonic moments: “upsprung from,” “bedbodied, unpeeled / from a fire fever,” “a woken orchid,” “not rigid like a grid.” I imagine a reading of these poems: dark as a cave, slight reverberation. A steady reading, each gorgeous moment spent. We can only imagine the ghost-forms of arrows and sails as each image is revealed in slim-lined verse. The book itself contains a few sketches, but if one wants a real look at the art, a Google search or museum trip is in order.

The most ubiquitous of Bourgeois’ work is that of her spiders. These huge arachnids peer from the grounds—the central spider is thirty feet tall and installed in Ottawa. The spider straddles buildings and dwarves pedestrians. One particular image of it is paired with a black and white portrait of the artist herself: her eyes are closed, or near-closed, and her hand is held out, a wrinkled span in front of her face, her dark hair pulled back and streaked white; these lines are a perfect continuation of the spider’s spindly legs. It is said these needle-like legs are meant to be an homage to Bourgeois’ mother, who repaired tapestry.

The act of repairing the self becomes a thread woven through Guthrie’s poems. In her poem “Spider,” Guthrie closes:

Maman, don’t

abandon me to

stalk the veritable earth

on metal tendrils

Without the accompanying sculpture, the italicization of Maman could indicate an intruding voice or an emphasis on the second language. We do know “A giant steel / Spider impends // outside the art / museum.” Could the voice be a small child addressing its mother, a vulnerability or an example of innocence, asking “don’t / abandon me”? Or could the voice be that of the artist outward or the spider itself? In truth, Maman is the title of the thrilling spider, a menacing and gorgeous presence. So then, if Guthrie wrote on slips, each line its own moment, then “abandon me” could be excised, become a request for solitude.

The collection opens and closes with a poem titled “Portrait,” each shivering out a few details of the artist herself. In the first, “the underleaf of reality is glinting,” which introduces the concept of mirrors, reflection, and looking inward. Soon, one is “Tracing each little sensation,” uncorking a “memory faucet,” each round word on the page a kind of Braille. What was it like for Bourgeois to draw forth each art object, for Guthrie to hold her instrument in her hand and sketch a response? Could they feel the ghosts of one another, “the lucid ankle / the hand clasp”?

The closing portrait is empowering: here, “she arose / arranging / Hones her hammer & swings it / through dusted air floes.” The subject holds the control—the artist who is opening up the world for viewers and not someone else for her. The poem and the book ends exquisitely:

And then, observing

sets her foot

on the spine of the riverBeating the long wing

of necessityup from clouds and caverns

Rebounding

So many shes are folded into this culmination: the triumphant artist, her figures, her poet. There is an opening out, a feat.

Konundrum Engine Literary Review is running a project in which two poets exchange work and translate it into their own language and form. One might wonder what would happen if Louise Bourgeois had a set of Guthrie’s poems from which to build sculpture. Likely, the result would be just as eerily beautiful.

***

Molly Sutton Kiefer is the author of the hybrid essay Nestuary (Ricochet Editions, 2014) and the poetry chapbooks The Recent History of Middle Sand Lake (2010) and City of Bears (2013). She is a founding editor at Tinderbox Poetry Journal and runs Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)