96 pages, $18.00

Review by Carley Moore

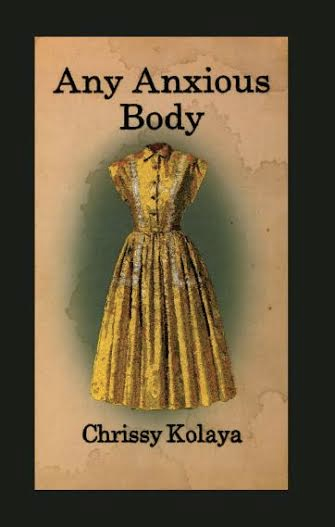

The cover of Chrissy Kolaya’s first collection of poetry, Any Anxious Body, is a drawing by Jess Larson of a yellow short-sleeved shirtwaist dress with a full skirt and white piping along the lapels and pockets. The dress floats in the blue and white watermarked background, as if on a dress form, inhabited by no particular body. Still, the dress is iconic and reminds one of the working-class American women in the 1950s who wore these dresses—mothers, aunts, grandmothers, wives, and girlfriends, all of them workers who tried to make a place for themselves as first- and second-generation Americans in small industrial towns. The dress is a ghost of sorts and the book haunts us, reminding us of the stories of love and loss, death and sacrifice, abuse and secrets at the center of family lore and history.

The book is divided into five sections, “Overheard,” “A Privileged Life,” “Reckoning,” “A World Familiar/Unfamiliar,” and “Diagnosis,” and moves in and out of overheard stories, family gossip, and the rooms of houses and hospitals. At the heart of many of these poems is marriage and love, but it’s an imperfect union—aren’t most marriages? Kolaya’s poems create an archive of images of missed connections, of the moments when men and women don’t make sense to one another. It’s this groping, both physical and mental, that first resonated for me in this collection. In “Kitchen,” the speaker insists,

“You will know

by the long lines of her legs

what she will say in her moving

and how to please her.

What she will mean/lying close to you at night—

I am careful” (14).

In “There They Stood Exactly as They Were Created,” the narrator, who functions as a reporter on a relationship that is both faraway and close, admits,

“The best feeling in the world—anticipation.

He waited for her to lean forward,

to tell him they were—

to tell him he should—But none of this happened” (60).

And in my favorite poem in the book, “The Very Thing,” the speaker, a daughter, as if imagining her father and mother in Italy, an affair, or the afterglow of sex,

“At the dinner someone says my name

He looks up/Remember what it looks like

and you will remember how it feels” (69).

This poem in particular has a Mad Men quality to it—a boozy overlay of missed connections and fucking that reminds me of Don Draper and his lost women. Koloya captures the way sex and love get stitched into the seams of a family.

The third and most powerful section of the book “Reckoning,” has at its heart, primary documents—the notes Koloya’s great-grandmother scribbled in 1957 in her hospital bed and a final list, “in someone else’s hand, a reckoning: [of] funeral expenses minus assets” (25). The historian in me found this section fascinating. I’ve always loved primary documents, and Koloya mixes her grandmother’s disjointed prose with her own narrative to create poems that are reminiscent of Gertrude Stein and Lynn Hejinian. These poems occupy what poet Erika Meitner, borrowing language from the French anthropologist Mark Augé calls the “non-lieux” or “non-place.” In this case, it’s the non-place of the hospital and the grandmother’s deathbed, which serves as a final waiting room. Woven into these lines is the story of the great-grandmother’s pregnancy and forced marriage to a man who the notes tell us “I disliked right from the start” (37). This marriage is so anti-climactic that “after it was over/we went to the A&P for groceries for her [the new mother-in-law]” (42). Near the end of this section, Koloya includes the final reckoning, in a careful script that reminds me of my own great-grandmother’s careful cursive in a diary of hers I just un-earthed. The list is chilling in its exacting detail (expenses include the cost of the night nurse, the funeral dinner, and stamps while assets include insurance policies, cash, and donations), but it’s also a record of a moment when every penny mattered and cost cutting was a kind of caregiving.

When my grandmother who is 87 recently handed me her own mother’s diary—a record of her time as a school teacher in a rural town and the moment she met my great-grandfather, a man who survived the great depression by becoming a bootlegger, I understood that I was being given a secret and as the only writer is our family, I was also being granted permission to tell. I have since written my own poems out of this artifact. It’s what many poets do. When they are children they overhear the family secrets so that later they can tell them to anyone who will listen. These poems are small histories, but they are histories nonetheless.

I’m bound to the women in my family in many ways, but after reading Any Anxious Body, I am reminded that family secrets often reside in objects—the notes by a bed and the shirt-waist dress. I remember trips with my mother to JoAnne Fabrics, the promise of each dress pattern, the drawing of it on the front of the package. The pattern was the dream of a dress. Sometimes the finished dress bore a resemblance to the dress drawn on the pattern sleeve, but often it didn’t. Sewing, writing, and loving each have their own challenges. I’m grateful to Kolaya for making those challenges visible.

***

Carley Moore is a poet, novelist, and essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The American Poetry Review; Aufgabe; Brain, Child; The Brooklyn Rail; Fence; The Journal of Popular Culture; Mutha; and Linebreak. Her debut young adult novel, The Stalker Chronicles was published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux in 2012. Follow her on Twitter: carleymoore2 or find her blogging at: carleymoorewrites.com

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)