Life Within the Simulacrum is a featured column focusing on technology & social media, travel & literature.

BY DALLAS ATHENT

–

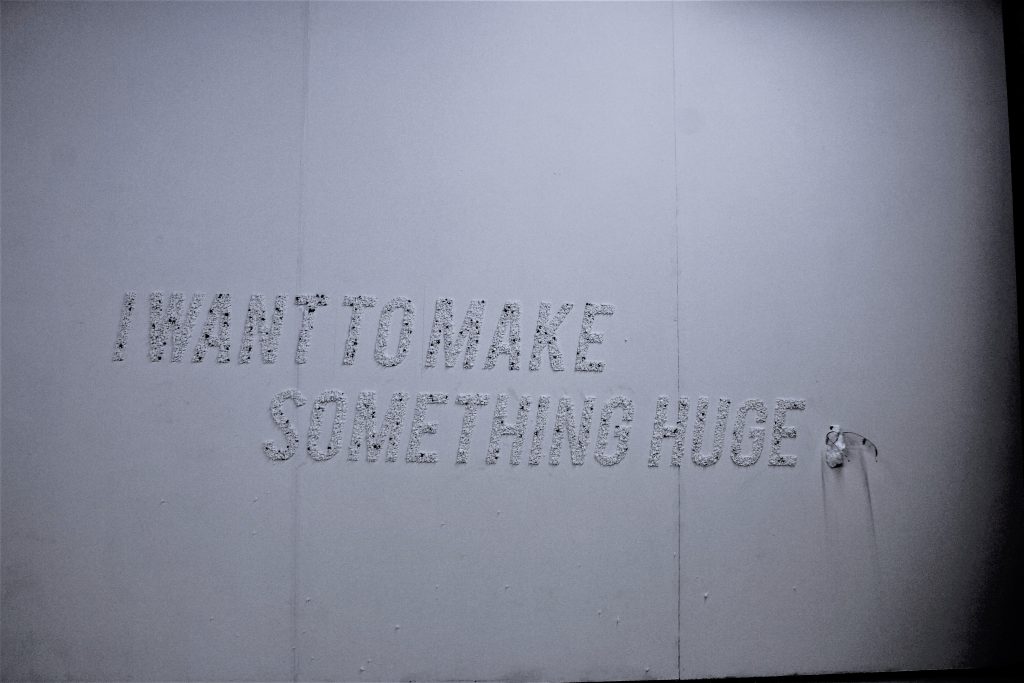

(I Want To Make Something Huge by Camille Yvert, 2018)

The use of text and technology in art, though two varied subjects, share a similar issue–both of these themes are accessible in a way that almost any artist can produce fairly decent work using them. Anyone can make a painting that says something, and because it says something, it impacts you on the surface. Same with technology–it’s current, and since we live our lives with technology in the modern world and we are used to such objects, art utilizing this subject can be easily familiar to us on a personal level.

But it’s not often work in either of these mediums hits home in a way that you deeply internalize it, which was exactly what was so shocking about a recent show I saw in London, rightfully titled HTTPS:// curated by IKO at Sluice gallery. Upon entry, a large purple wall reads “Disappointingly Territorial” in dripping petroleum jelly–a work by Matilda Moors. Like a new-wave horror story, it blatantly depicted my own reflection as a young woman, navigating a need to create work out of crisis–a plea to be self-aware, honest and demonstrate talent for consumption all at once. These are common themes that transcend time for artists of all disciplines. However, they’re especially relevant during a technological revolution when the quest for love can so easily exist in the simulacra where we connect with others through web-based interfaces. Is this what the artist intended with this piece? I’m not sure, but it was a welcoming entryway to the other works in the show which equally addressed this particular sort of existential angst.

(View of HTTPS:// including work by Matilda Moors, Sam Blackwood & others)

Additionally in HTTPS:// Sam Blackwood created a piece titled Green Bottles, which consisted of bottles of wine with personal branding and flowers stuck in placed in clusters around the gallery. I visited the show weeks after it originally opened and the flowers had wilted. The progress in time was a morbid representation of what happens to the artists’ spirit as we succumb to self-promotion through the web. But maybe that’s just me projecting my personal issues. If you think this is the point of the exhibit in its entirety, however, keep reading. There’s a bit of a plot twist.

(Green Bottles by Sam Blackwood, 2018)

HTTPS:// had many other attributes that were carefully crafted, creating depth to what seemed so simple at a glance. There was a hard-drive that you could upload to your computer full of art by Chris Alton, a custom-made bench with plug-ins to charge your phone and IKO even provided free WiFi so attendees could freely find the artists online without draining their data usage. As I said, I initially gathered pieces of the exhibit were about both the pressure, longing and anxiety of having to self-promote as an artist, but after sharing this sentiment with Oly Durcan of IKO, he in turn, asked me a question. “What’s the purpose of an artwork in an exhibition that someone’s traveled to? We’re not telling people what the answer is. It’s an entry point.” I told him I felt like we were in the simulacrum (which literally 100% of people who have ever met me are probably sick of hearing by now, but hey, you’re here reading this review in my column just on that subject, so maybe you haven’t spent enough time with me yet–just wait!). More explicitly, I explained that when social media came out, it seemed a new way for artists to promote themselves while avoiding commercial influence, whereas now it’s the opposite. People now seem to make music, or paint or write in order to gain a larger following online. The validation through attention on the web has almost overcome the validation of someone buying your work. In the end, isn’t the point of making art to express your ego, or achieve love? Does social media not replace this purpose? I didn’t ask these last couple of questions in fear of seeming vain, but I thought it.

(Custom bench made by IKO for “HTTPS://, including “Live and Direct” By Dani Smith, 2018)

But Oly said something comforting. He said, “I think it’s a little like that, but it’s kind of–” and then did a motion with his hands like the scales were going back and forth. He was right. I was just being pessimistic 🙁 Upon further thought I realized the exhibition isn’t a critique of social media use in an artist’s life, instead, it’s about where does the experience of an artist start and finish.

I left the gallery wondering the same thing. I myself, have just moved to London and this was the very first review I’ve done of a show here. Where in the simulacrum do my relationships with those whose work I review begin and end? Life is art and art is life. We know this. In an attempt to make sense of it all, I went home that evening and made an Instagram post about my experience at the show, hoping it was somehow getting so meta and I could connect with my readers and the artists whose work I just admired. That was what HTTPS:// hoped to achieve, and dammit, I was going to try it out. I tagged Matilda in a selfie I took earlier that day in front of her work, as her’s was the one that stuck out to me when I first attended the opening–and then I got a notification hours later, that she followed me back.

IT’S KIND OF HARD TO EXPLAIN (IKO) is an artist and curatorial collective based in London that has been operating since 2017. HTTPS:// was on view from September 14th, 2018-October 6th, 2018 at Sluice Gallery in London

–

Dallas Athent is a writer and artist. She is the author of THEIA MANIA, a book of poems with art by Maria Pavlovska. Her work, both literary and artistic has been published or profiled in BUST Magazine, Buzzfeed Community, VIDA Reports From The Field, At Large Magazine, PACKET Bi-Weekly, YES Poetry!, Luna Luna Magazine, Bedford + Bowery, Gothamist, Brooklyn Based, and more. She’s a board member of Nomadic Press. She lives in The Bronx with her adopted pets.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)