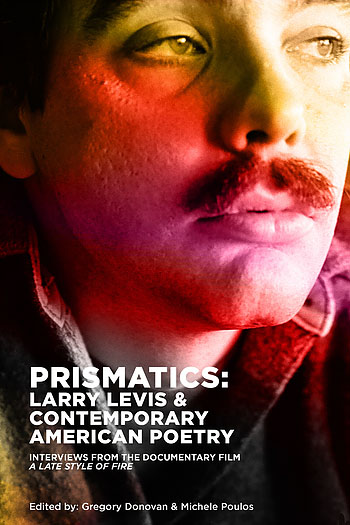

Prismatics: Larry Levis & Contemporary American Poetry (Diode Editions, 2020) is a collection of the full-length transcriptions of the extended interviews Gregory Donovan and Michele Poulos conducted with a group of America’s most notable poets—including two U.S. Poet Laureates—in making the documentary film A Late Style of Fire: Larry Levis, American Poet. These discussions cover not only their relationships with Levis and his poetry, but also more wide-ranging commentaries on a broad spectrum of American literary life.

Here, they sit down with Kathleen Graber, author of new poetry collection The River Twice (Princeton University Press), winner of the UNT Rilke Prize.

Michele Poulos: Tony Hoagland, in his essay “Flight and Arrival,” discusses Levis’s various muses: oblivion, self-annihilation, extinction of the self, the end of his life, and perhaps—I’m not quoting precisely—the wish to be both present and yet always elsewhere, a longing to be nothing, which I think is provocative. Then you have what might be the other extreme, which is somebody like David St. John who says in his essay in A Condition of the Spirit, “What I see happening is a real love of the world.” So, those are distinctions that I’d like to talk about in depth.

Kathleen Graber: When I was reading several essays, I was struck by a desire, on various critics’ parts, to make an either/or claim: you’re either nihilistic or you’re visionary in a sort of spiritual way. You’re in love with the world, or you’re in love with your own death. What I like about Levis, which makes him unique, is that it’s always both; there’s such a complexity and simultaneity of existing in those states. I’ve read essays where that has been described as sort of ping-pong, that he’s always oscillating between wanting an annihilation of the self and wanting a sort of visionary, Whitmanesque embrace of the world. He believes in the political reality—and that the political reality matters to him, as an heir to Philip Levine—or that he doesn’t at all, and he’s a surrealist at heart and an image-maker and that he’s much more interested in his interiority than he is in any kind of exteriority, and that the most you could say is that he somehow is constantly penduluming back and forth between those two impulses. It was interesting to read about that, because I certainly see all of that in his work.

But for me, it’s all stew. [Laughter.] It’s not “and then carrots, and then potatoes, then meat.” It’s sort of like, “No, it’s all in there, together, at the same time,” and it doesn’t feel like a contradiction, because poetry isn’t about putting forth a philosophical program or a metaphysics. He’s not obligated to choose; he’s merely obligated to be honest about what it feels like to be human, and I think that that is what it feels like to be human. I think that we do realize that people actually really do suffer. There actually really is pain and political reality and oppression, war, violence in the world, and that at the same time we have an inner life that can be, at times, completely disconnected from that, and that we can be preoccupied with our own interiority given the extremity of our own personal life at the same time that we are aware of what’s going on in the world around us—those aren’t mutually exclusive psychic states, for me anyway.

So that’s one way of breaking out of a fractious interpretation of his work.

There’s been a fascination with saying he’s a nihilistic poet or a morbid poet, and it gave me a lot of pause because I had to stop and think, “Well, what do people mean when they say something like that, when they use a world like ‘nihilism,’ which is a sort of slippery term. And I wonder whether some spiritual people will simply say, “If you have no faith, you’re nihilistic,” or, “If you don’t believe in an afterlife, that’s a kind of nihilism,” or, “You don’t believe the world has an objective meaning other than whatever meaning we ascribe to it, and that’s nihilism.” I think that in Levis’s work, there’s always a sense of another world beyond this one. I don’t think he believes in an afterlife per se, but I think he feels a profound, ineffable––and that’s a term that comes up in more than one poem––something, something that is beyond our capacity to articulate it, that infuses the world with what feels to me like tremendous . . . tenderness. So I don’t see the poems as nihilistic; I see them as heartbreaking and sad, and there is a loneliness, but I think that all of those emotions come out of this tremendous sense of being unable to fully connect in a communion with the world. And I think that’s the human condition; I think we all feel it. I think if his poems are moving and popular, it’s partly because he, more than any contemporary poet, captures that longing, that sense of being haunted by an elusive otherness to which we belong and don’t belong.

I don’t know if that’s going to translate or make any sense, but I was just reading one of his own essays, and he spoke a lot about animals in poems. Horses are so essential. Horses and stars are probably the two most important images—or among the most important, recurring images—in his poems. And so I stopped when I read that, because I’m always so moved by his horses. And what he says about horses is that the horse is the poet, the horse stands in for the muteness of the poet, for what the poet can’t say but wants to express, that that’s the function of animals—their languagelessness. On the other hand, there’s also a sense that they have access to another realm—and whether these two things are related, whether they’re corollary conditions—that because they have no language, they have managed to retain and have access to a sort of instinctive understanding that we have now lost—because one of the barriers for us might be intellectualization; it might be consciousness; it might be language, which might be the byproduct of consciousness.

And so we look at them, and we are filled with a kind of envy for their ability to simply be, that they’re mortal beings that have, as far as we know, no preoccupation with their own mortality. They have no ambition––and there’s another thought connected to this––perhaps beyond being what they are, and so they don’t struggle with a sense of self-identity. You know, a horse is a horse. Having said that, a horse is a particularly fascinating animal to have chosen as your avatar, because there are very few purely wild horses left in the world. Horses are essentially domestic, broken, corralled beings. So in that way, they are the absolute threshold between realms—maybe dogs would be another example of these beings, or cows, but cows don’t have the grace of a horse; a horse retains more of its wildness than a cow or a dog, yet it’s a domestic animal; it’s more powerful in some way and has a lot of really primitive associations attached to it—so, the horse is a threshold between a human world and a purely animal world.

And so, I’d hate to use “unconscious” or “subconscious,” but at the level of metaphor, the level of image-making, it’s not by chance that this is the animal to which he’s most attracted and in which he finds a corollary. Some of the horses are workhorses, farm horses; some of the horses are racehorses. And it’s hard not to think of the racehorse as a metaphor for the poem, or for the poet, right? It’s a thing that wants to transcend itself, that runs as fast as it can to the point of self-destruction, not because it’s pursuing self-destruction. If it destroys itself it’s a byproduct of simply running really, really fast to doing the thing that is most in its essential nature to do. It has been put here to do that, and in the process of doing that, it inadvertently injures itself because it has no sense of its own limitation. So if people are going to ask about the connection between creativity and self-destruction, I don’t believe that people set out courting self-destruction; I feel that they may have an obliviousness to their own limitations that then, in the pursuit of a kind of creative transcendence, leads them to fall into a pattern of self-destruction.

MP: Would you mind, for the sake of the movie, revisiting that idea about limitations? I know that there was a complete overarching idea, and maybe we could try to encapsulate it for the film.

KG: I’ll try. I’ll have to go back to horses. Is that okay?

MP: Sure, yes.

KG: So, I can refer to “There are Two Worlds.” It’s not a poem that’s actually anthologized out of Winter Stars. It wasn’t in the Selected, and I can understand why. It’s not a poem without flaws, but it’s a poem of so many achievements—and there’s a recurring metaphor. First of all, the poem starts with the line, “Perhaps the ankle of a horse is holy,” which, when I read that for the first time, I just had to stop. That was as far as I got. I closed the book and said, “Okay, I’m just going to think about that one for a while.” I can’t articulate why I find that to be such a moving line. I think some of it is personal. My father loved the horse races, so that a big bond that I had with my father was about horse racing, the history of horse racing. There was a great horse, War Admiral, and he actually was cut stumbling out of the gate but won the race anyway. He was there in the winner’s circle, bleeding out from his ankle, in fact. And then for a long time––we don’t have it now––we had a picture of my father as a bystander, because it was during World War II, and there weren’t many spectators at horse races in the middle of the war, and so for the few spectators who were there, you could get onto the track and you could get very close to the horses and to the action. So, my father was in the winner’s circle with War Admiral. Then minutes later, the horse was taken away covered in blood.

Now, as soon as I say that, I question it. I’m like, “Is it War Admiral?” I’m out of practice. Is it a different horse? I want to say, “Could it have been Count Fleet?” Then I think it was Whirlaway. But, maybe I’ve gotten it wrong. This is where I would have to Google it. Anyway, “Perhaps the ankle of a horse is holy” moves me deeply, and it’s simply because so much power rests on such a tiny, fragile joint. And so the poem goes through a lot of moves in a very quick space there, and it gets to a point where it says—it repeats itself— “If the ankle of a horse is holy, & if it fails / In the stretch & the horse goes down, & / The jockey in the bright shout of his silks / Is pitched headlong onto / The track, & maimed, & if later, the horse is / Destroyed, & all that is holy // Is also destroyed: hundreds of bones and muscles that / Tried their best to be pure flight, a lyric / Made flesh, then // I would like to go home, please.” And I have always read that as a metaphor for the work of the poet, that the poet is a lyric made flesh. It wants to be transported. It wants to become the poem in some way. And so a poet who, in the act of writing, has that rare experience of being carried away by the process is very much like a horse wanting only to fly, running as fast as it can down the track. And in some way we might say that one part of our being is the horse; there’s another part of our being that is “the jockey in the bright shout of his silks.” And as a byproduct of the horse’s exuberant desire for flight, the jockey is maimed. That is the most articulate expression that I can think of to explain why sometimes creative people suffer tremendously, seemingly at their own hands. I always tell my students, “You don’t need to look for sorrow; you don’t need to look for heartache if you think that that’s where great creativity comes from. Just wait. You don’t have to go looking; it will find you. That’s part of being human.” But I think there is a mythology that that is a conscious courting of the darkness, and to me, I don’t think it is. I think it is this other thing, where something out of control happens, an unconsciousness of the limitation of the being.

MP: Do you remember being first introduced to his work?

KG: For someone as old as I am, I came to poetry late in my life, and the consequence of that is that by the time I first read Larry Levis’s poems, he was already deceased, and I think it may have been Mark Doty who said to me, “Here’s a poet you’ll really like. Go see if you can find it.” And there was a really fabulous independent bookstore on the campus, or what came to be called a campus, on Washington Square Park. It’s now a bodega. But they were going out of business, and that was where I bought Winter Stars. It was the only Levis book left on the shelf, and that was the first one that I bought, and it was a really transformative moment for me. Now if anyone were to ask me, “Who are your essential poets?” I would say, “Levis and Gilbert and Charles Wright.” And up until that point, I would have said, “Charles Wright.” So I came to Levis and Gilbert later than I came to Charles Wright, and I think that anyone can see the similarities between Wright and Levis. When I read Charles Wright, I thought, “Oh, I’m in the presence of a mind that works like my mind works, how that moves: it’s fluid, it’s moving, it’s shifting, anything can be in the poem, it goes from topic to topic.” I called it “juggling.” And the things that are being juggled are not always similar. I think that Levis is a more extravagant juggler than Charles Wright is. Charles Wright has got his act much more under control, and I think Levis is juggling chainsaws and flaming batons, simultaneously, and then with a bowling ball and a bowling pin—so, things of very dissimilar weight, size, gravity. I feel like with Charles Wright, it’s much more orchestrated. Levis sometimes feels out of control, but that’s the exhilaration of it, right? If there’s not a churning chainsaw [laughter], you lose something. Three bowling pins are not as exciting.

MP: In an interview with J.D. McClatchy, Wright was asked about some of the religious motifs in his poems, and McClatchy basically suggests that Wright’s argument is “the absence of belief.” And I asked him if he would agree with that, and he said, “Oh, I absolutely agree with that.” Then I asked him about Larry’s argument, and I guess I’ll ask you the same thing, if that’s something that you’re comfortable talking about. What is the argument Larry makes?

KG: I don’t think it’s about the absence of faith. I think Charles Wright has less faith than Larry Levis has. Charles Wright has a tremendous fascination with faith and with spirituality, and he, I believe, wants very, very much to believe, wishes he believed, but it doesn’t work that way. Unfortunately, you can’t make yourself believe. So if the horse is recurring and stars are recurring in Levis’s, wind might stand in in Charles Wright’s work for the divine or some sense of something bigger than we are that moves through us. It’s invisible; we can feel it, but we can’t capture it. If we hold it, if we still it, it’s lost. So, it’s not completely true that there isn’t a presence, or there aren’t hints in Wright of some wavering of his atheism. You can ask him if he feels that. I feel like sometimes he thinks, “Well, maybe I’m not as certain as I used to be,” or maybe, “Today I’m not as certain as I was yesterday. Tomorrow I can be certain again. But right now, I don’t know. Something feels different.” And with Levis I feel like there’s always a sense of, “I have no faith in an afterlife or a god or a design or a plan or anything like that. That’s not what I feel; I just feel a sort of faith that it matters in some way––that we don’t suffer without reason, or that it doesn’t matter if we could make the world a better place, or we could alleviate our own sorrow or someone else’s sorrow––that those things do matter profoundly. They don’t matter because there’s another world in which we’ll be rewarded or not be rewarded; they matter profoundly because people shouldn’t suffer in their lives. And if we can make someone’s life better or our own life better, we should do it. And if we can find a way into consolation or a way into feeling like a part of the universe, then wow, let me try as much as I can; let me chase it as far as I can and see if I can’t pin it down. But part, of course, of its beauty is that it resists us, that feeling of belonging.” But I believe he believes that it’s out there, and it’s worth pursuing. And that seems like a kind of faith to me.

___________

Gregory Donovan, the film’s producer, is the author of the poetry collections Torn From the Sun (Red Hen Press, 2015), long-listed for the Julie Suk Award, and Calling His Children Home (University of Missouri Press), which won the Devins Award for Poetry. His poetry, essays, and translations have been published in The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, Crazyhorse, Copper Nickel, TriQuarterly, and many other journals. His work has also appeared in several anthologies, including Common Wealth: Contemporary Poets of Virginia (University of Virginia Press). Among other awards for his writing, he is the recipient of the Robert Penn Warren Award from New England Writers as well as grants from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and fellowships from the Ucross Foundation and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Donovan has served as a visiting writer and guest faculty for a number of summer conferences and low-residency programs, such as the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Chautauqua Institution Writers’ Center, and the University of Tampa MFA program. Donovan is Professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he helped establish its MFA program, and he is a founding editor of Blackbird: an online journal of literature and the arts.

__________________

Poet, screenwriter, and filmmaker Michele Poulos directed and produced A Late Style of Fire: Larry Levis, American Poet. Poulos is the author of the poetry collectionBlack Laurel(Iris Press, 2016) and the chapbook A Disturbance in the Air, which won the 2012 Slapering Hol Press Chapbook Competition. Her screenplay, Mule Bone Blues, about Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, won the 2010 Virginia Screenwriting Competition and was a second round finalist in the 2017 Sundance Screenwriters Lab competition. Her poetry and fiction have been published in The Southern Review, Copper Nickel, Smartish Pace, Crab Orchard Review, and many other journals. She has won fellowships from the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing and the David Baldacci Foundation. Poulos has taught creative writing courses at Virginia Commonwealth University and Arizona State University, and has been invited for readings and as a guest lecturer at the College of William & Mary, University of Utah, Drew University, Columbus College of Art & Design, and the O Miami Poetry Festival, among other universities and writing conferences. She is currently at work on a feature-length documentary about women’s participation in Mardi Gras.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)