PANK Team Member Emily Jace McLaughlin sat down with [PANK] 2019 Nonfiction Book Contest Winner J’Lyn Chapman (as selected by Maya Sonenberg) to discuss her newly released essay collection To Limn / Lying In.

Taking its inspiration from the artist Uta Barth’s photographs of the sun as it enters her home and the poet Francis Ponge’s notebooks kept during the German occupation of France, this collection of lyric essays contemplates light as seen through the domestic space and its occupants, predominantly the author’s young children. Meditations on how through light the external world enters into and transforms the private spaces of self and home inextricably link to the author’s writing on life, or the giving of life. These vocabularies weave and tangle while the essays’ forms depict the staccato rhythms of thought and the estrangement of time one experiences when living with children. The essays can be read as standalone pieces, yet build on one another so that patterns emerge, like the obviation of how language serves to illuminate and veil meaning, the repetition of and ekphrastic approach to religious imagery, and the ineffable experience of depression. These essays continually return to the speaker’s admission that the life one gives another is ultimately unsustainable and that despite this catastrophe of living there is the resilience and bewilderment of being together.

Emily Jace McLaughlin: First of all, PANK is so excited to have the opportunity to publish your profound book. It is equal parts philosophical, poetic, innovative, gorgeous. It’s the type of book that inspires writers to write.

I’m

so interested in how you write about how your experience of how the light of

the external world enters the private spaces of your home, body.?

So much of new motherhood, of motherhood, takes place inside walls, inside of a

room, inside of oneself. Which piece came to you first, can you tell us

about the genesis of To Limn / Lying In?

J’Lyn Chapman: First of all, thank you for your kind words. So much of my inspiration comes from other writers, so it’s an honor to inspire in turn.

One summer before I had children, I began a meditative practice of describing the light as it entered my home early in the morning. I was having trouble staying asleep, so rather than lying in bed worrying, I got up and watched the sun rise. It was truly a practice rather than a project, but after taking an online class with the poet Kristin Prevallet, I started to feel that the practice revealed something interesting about language and writing. The essay “To Limn” came out of that. The next summer, I was pregnant, and that’s when I wrote a first draft of “Consenting to the Emergency / the Emergency as Consensuality.” But it wasn’t until the baby was born that I really started to consider a book. My good friend and colleague Michelle Naka Pierce helped me to see the resemblance between the previous year’s meditations on light and my current feelings of confinement and isolation as I watched that light in a period of what used to be called “lying in.” With that framework in mind and a very real need to write in order to survive, the other essays tumbled out.

EJM: To write in order to survive resonates. I will quote this passage, for readers who have not yet read the book. “Yet, the light shows me my home is an ambient field, as the photographer Uta Barth says of her own home. I see the light first and then that which it illuminates. I feel a calm acceptance of the accumulation of these objects and while I see them differently, I also see past them. It’s like they are fully present and also transparent. The baby’s presence does something similar.”

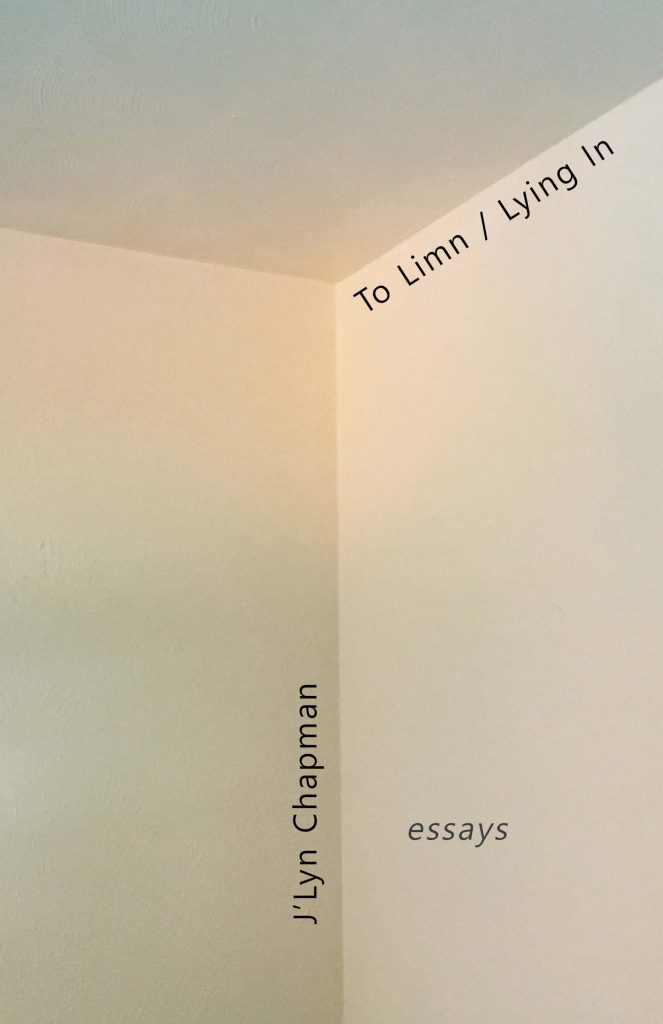

The visual image we see on the cover of the book—the light in the room, without object. I assume this was inspired by Uta Barth’s photography? For readers not familiar with her work, do you mind expanding a little how it inspired the book, the cove?. Why you decided on this image of the light entering the empty room?

JC: Uta Barth’s photography, in the most general sense, draws attention to the process of looking. I say process because some of these photographs, for instance those of the series nowhere now, are only subtly different from one another, giving the impression that the camera captures and slows down the mechanisms of the eye. At the same time, Barth maintains the camera’s flaws, like lens flare and overexposure, to remind us that these images are made, artifice, that the camera provides a kind of frame that obviates our looking. This latter point is important because the subjects of Barth’s photographs can be totally banal—wintering trees and telephone poles outside of a window, the panes of glass that comprise the window, or, in the case of the series …and of time, sunlight on the walls and floor of her own home. The photographs seem uncomplicated, but after studying them, I found that this simplicity rounds back on itself to reveal the other side of simplicity—a process of perception so complex it’s ineffable. I always want to write there: in the ineffable

In an interview with Matthew Higgs, Barth says of this series:

“I chose to photograph wherever I happened to be, the environment most familiar to me—and that environment was my home. What interests me the most is that it is so visually familiar that it becomes almost invisible. One moves through one’s home without any sense of scrutiny or discovery, almost blindly, navigating it at night, reaching for things without even looking. I am engaged in a different type of looking in this environment. It is truly detached from a focused interest in subject. Instead it provides a sort of ambient field.”

I had long admired Barth’s photography, but it wasn’t until I tried to practice the gaze of the camera that I found my own experience with my home revealed. I couldn’t actually be a camera—that’s one thing I learned about meditating on light—so I took some inspiration from something Cole Swensen said in an interview my students did with her: “Ekphrasis is a way of questioning framing; when the subject is an image, the frame’s already there, but when you slide the ekphrastic gaze over to a less obviously artistic object, the gaze itself must establish the frame through selection, arrangement, and emphasis; that ekphrastic choice creates the object that is its subject.” Since I couldn’t really have a photographic gaze, I thought I could try to have an ekphrastic gaze. I wonder now if ekphrasis is the poet’s camera.

As for the book’s cover image—I considered several photographs my student Chloe Tsolakoglou had taken. Her photographs of windows and domestic spaces, which simultaneously suggest languor and agitation, are almost too perfect for the book. I opted for a photograph I had taken of color that had collected in the corner of what was my office before my son was born and it became his bedroom. It’s a more symbolic and associative image than Barth’s photographs—which are totally nonnarrative—or Chloe’s—which are like little lyric poems. For me, the image shows how light can illuminate and obscure—there’s a trompe l’oiel quality even though the image has not been manipulated. As well, this intersection of planes reminded me both of an open book and of an intersection of our three lives, the children’s and mine.

EJM: That is a fascinating way to think of the cover and makes me also think about the way you omit dialogue. Was this to contribute to a feeling of estrangement in one’s body as a mother, or to have lost a connection to it, and to time? How does this choice mimic what you wanted to explore about depression too, if you would like to talk about that? I am thinking of your lines “To give life to another and to know it cannot be sustained. To be surrounded by joy and not feel it.” Yet your last brilliant line, you give to your baby’s voice.

JC: I didn’t intentionally omit dialogue, but I did choose to present others’ words in italics but otherwise integrated into my own thought. Maybe it wasn’t so much because of feelings of estrangement but because I wanted to be clear that I was the mechanism for the book itself. These were my perceptions, my experiences. Even in the instances in which I turn toward other texts, which I did a lot less of in this book than in my first book, I wanted to claim my own thought, even if that thought is flawed, as it so often is.

Perhaps to be even more specific here, I think of the experience of a child coming into language. It’s very strange for the first few years—you’re not in conversation with a child, you’re watching a child use language. It’s a rare phenomenon to watch language come into being, to see the signifier and signified simultaneously. (Although I have had this experience while reading certain kinds of books.) I didn’t want the children’s language to be all signs that we just read for meaning. I wanted to show what it is like to see the sign split apart.

EJM: Did you think of the book’s structure in terms of the grid of language, the form taking shape almost as the unconscious, prelanguage?

That’s such an interesting idea. I didn’t think of the structure of the book that way, but it does remind me of the artist Mary Kelly’s Post-partum Document, which I would describe as a scrupulous documentation and analysis of her son’s first three years of life, most notably his coming into language alongside her own commentary as mother and analyst. (I’m especially interested in her use of the grid, so it’s interesting that you should use this language.)

I thought more about light in terms of structuring. I wouldn’t say that I followed this strictly, but I did think about a moon phase while organizing the book. I thought of gradually bringing in more lightness (if not light) and then allowing darkness to come back in. I think the book opens and closes with a feeling of dimness, sadness even. I wondered if it needed to be lighter or more hopeful in the conclusion, but then I decided to allow it to end realistically.

EJM: Told in vignettes, essays, much of this reads like prose poem. It’s hard to not think of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets here in all the best ways. That your use of light works as her use of the color blue. Was Bluets an influence and are there any other works that informed your spiraling structure you would like to share with us?

JC: Bluets inspired me insofar as when I read it, I felt an opening of possibility, like Nelson’s book had given me permission to allow my thought to take its own shape, to cross lyric and prose modes. It was not an immediate influence on this book, but it certainly has had an impact on my writing. In some ways The Argonauts is an even bigger influence, not because of its style so much as its quality of thought. It has so much integrity, is so full and uncompromising. And the birth-death scene at the end—after reading that, I realized that it would be futile to write about actual birth when Nelson had already done it so beautifully. For the most part, I actually tried to include my influences directly in the book itself—Francis Ponge’s notebooks, Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter’s Day, and Uta Barth’s photography, as well as Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s Hello, the Roses and Etel Adnan’s Sea and Fog, which were aesthetic and philosophical inspirations. A book I did not include but that changed me deeply while writing was Virginia Woolf’s Moments of Being. I read this while nursing my son on the recommendation of my writing teacher Jenna McGuiggan. I found Woolf’s writing of her mother moving but especially her idea of “moments of being,” in which the eye and mind and soul seem to apprehend truth simultaneously. I wanted to write those moments of being. Not just what I saw but what what I saw revealed about what I didn’t see.

EJM: I was particularly struck by this piece’s title—“Consenting to the Emergency / the Emergent as Consensuality” you mentioned as one of the earlier essays you wrote. To quote from it, “The mother is both the metaphor and the practice of what this could mean—in the self-sacrifice that produces pleasure, as well as in the negotiation of contingency that an ongoing emergency, both boring and surprising, necessitates. This being together could almost be religious. The miracle is not the other’s coming into being but that I could survive the emergency of it with them.” Here, you juxtapose the pain of labor with miracle. Consenting to the emergency suggests responsibility or owning the decision as the mother. Did you ever feel a responsibility as a mother writing about the reality of labor or motherhood to offer optimism, or positive imagery? Miracles? Light? Maya Sonenberg, who selected your manuscript, wrote this of it “These essays continually return to the speaker’s admission that the life one gives another is ultimately unsustainable and that despite this catastrophe of living there is the resilience and bewilderment of being together.”

JC: I definitely felt some pressure to be optimistic and positive. As any mother knows, once your body presents itself as with child, you become interpellated by all the narratives of mothering, most of which are completely unrealistic and self-righteous in their positivity. Even in a basically secular culture, we tend to still understand motherhood as miraculous. As a writer, I had no desire to evoke those boring, pre-established narratives, but as a person who identifies as a mother, I continue to find the narratives oppressive and even traumatizing. And yet, I am a person who values survival. And I don’t think that a person can survive without resiliency, hope, and togetherness. So at times I wanted an essay to be a provocation of the narrative while another essay might be a bit more explicit about what it could mean to survive. For me to survive. I continually ask this question: how can I accept reality—which includes the reality of the other and the reality of my self—so as not to be crushed by it? I guess writing is a way of accepting it but also of changing it. That is the light I can offer.

EJM: Are you optimistic that the narrative of motherhood is being reinvented, rewritten? What types of literary contributions would you like or hope to see?

Yes, definitely. I started out answering this question by listing every book and writer who I see reinventing the narrative of motherhood and then realized there are too many to list. And then I started wondering if there are all of these writers rewriting the narrative of motherhood, why did I still feel so oppressed by narratives that didn’t work for me? Why didn’t I turn to these other narratives? Why didn’t I know about them? I think the answer is that most of the innovative and inclusive narratives I’ve encountered, I discovered after I was a mother. I think in part it’s because my attention became attuned to these kinds of narratives, but I also think it’s because motherhood is often seen as a niche topic. Like unless a person has an interest in motherhood, that person isn’t going to pick up a book that takes mothering as its subject. But this is where I want to push back. To rewrite, provoke, or trouble a narrative of anything, one has to be concerned with how language works, how words make meaning, as well as with bringing in that which has been marginalized, refusing to neutralize contingency, and suspending closure. The texts that I think of that reinvent the narrative of motherhood also do these things, and yet I don’t know that I’ve seen them discussed this way. So I don’t know that I need more contributions from writers (although I encourage it) but different approaches from readers and critics. I want there to be a critical discourse about the ways in which people who take as their subject mothering (or parenting) are engaging in practices that are ethically, politically, and philosophically radical.

EJM: Do you know what form your next book will take? What can we look forward to?

That’s a great question. I’m not really sure what this will look like, but I do know that I want to write about cloth, texture, the sensation of clothing; that I’d like to include actual images in the book, most likely photographic images; and that I’d like to conduct practice-based research. I had also planned some archival research, but I fear that the pandemic might have stymied that idea. But there are lots of textiles and clothes in my house, so there’s plenty to work with here. And so what I might end up with is yet another book based in the domestic space—which is actually fine with me. Some of my favorite books are about women stuck in houses.

J’Lyn Chapman serves as an Assistant Professor in the Jack Kerouac School at Naropa University. Her book Beastlife was published by Calamari Archive in 2016. She has also published the chapbooks A Thing of Shreds and Patches (Essay Press, 2016) and The Form Our Curiosity Takes (Essay Press, 2015).

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)